Dorothy Day Biography Raises Universal Questions

by Dana Greene

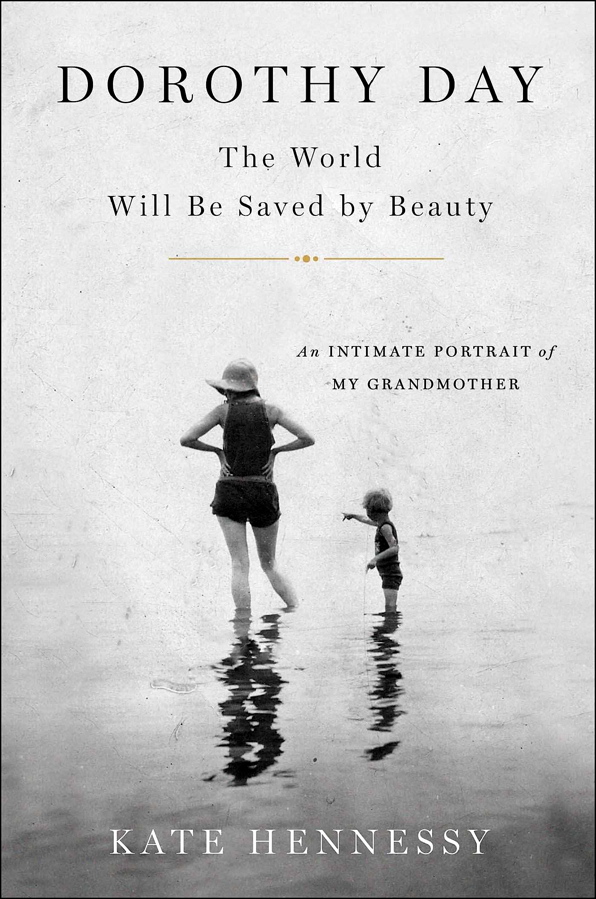

Dustwrapper art courtesy Scribner; simonandschusterpublishing.com/scribner

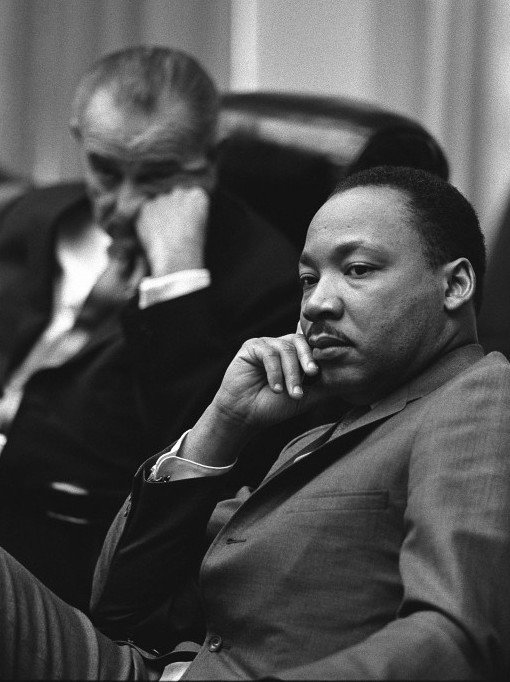

Who was Dorothy Day? In his address to Congress, Pope Francis named her an American icon of the stature of Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr., and New York Cardinal Timothy Dolan is among those moving her case forward for canonization. There are abundant materials documenting Day’s life and contributions — her autobiographies, letters, diaries, hundreds of her Catholic Worker columns, and a spate of biographies by Robert Coles, Jim Forest, William Miller and others.

One might ask whether another biographical venture, this one written by Day’s youngest granddaughter, might be redundant or sentimental? It is neither. Kate Hennessy’s biography, Dorothy Day: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty; An Intimate Portrait of My Grandmother (New York: Scribner, 2017) offers valuable insights into understanding this “complex,” “restless,” “bullheaded,” “judgmental” and “contradictory” woman who in her life railed against being referred to as a saint. It is a clear-eyed, tough but tender telling of Day’s life that goes far in saving her from the hagiographic “embalming” that so often accompanies saint-making.

Hennessy’s “insider” story is unique, a family biography linking Day with her daughter, Tamar, and Day’s nine grandchildren, most prominently Hennessy herself. It opens with the story of Day’s early life, her sense of not belonging, and then the Bohemian years of this “Northern Communist whore” in the 1920s and 30s.