Beginning with Witness: An Interview with Mark Johnson

Peacebuilding illustration courtesy myzimdialogue.com

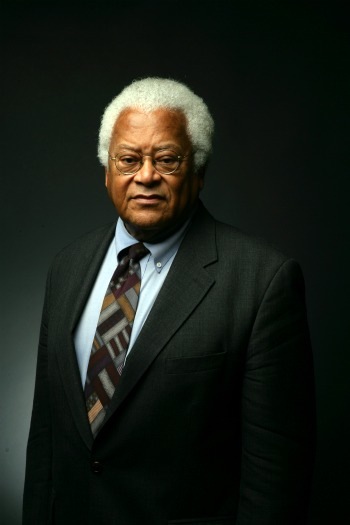

Preface: Mark Johnson was Executive Director of the Fellowship of Reconciliation (2007-2013), an organization that stood in opposition to two world wars and helped foster the civil rights movement’s ethic of nonviolence, in addition to being an early advocate for interfaith dialogue. Under his leadership, the FOR learned to find a place for itself amidst the proliferation of institutions—both religious and secular, governmental and civil—that claim the mantle of making peace. The interview was conducted in December 2009. Please see the notes at the end for further information and acknowledgments. NS

Nathan Schneider: Since its founding, how has the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) been involved in promoting peace around the world?

Mark Johnson: The Fellowship of Reconciliation began in 1914, when an English Quaker and German Lutheran agreed that they wouldn’t let the emerging war separate the fellowship they had established. A year later, one of their mutual friends, John R. Mott, invited them to form an organization at a conference in Long Island, and there, in 1915, the FOR was established. The early work, which helped frame FOR’s efforts through the Vietnam War era, had to do with the right to conscientious objection.