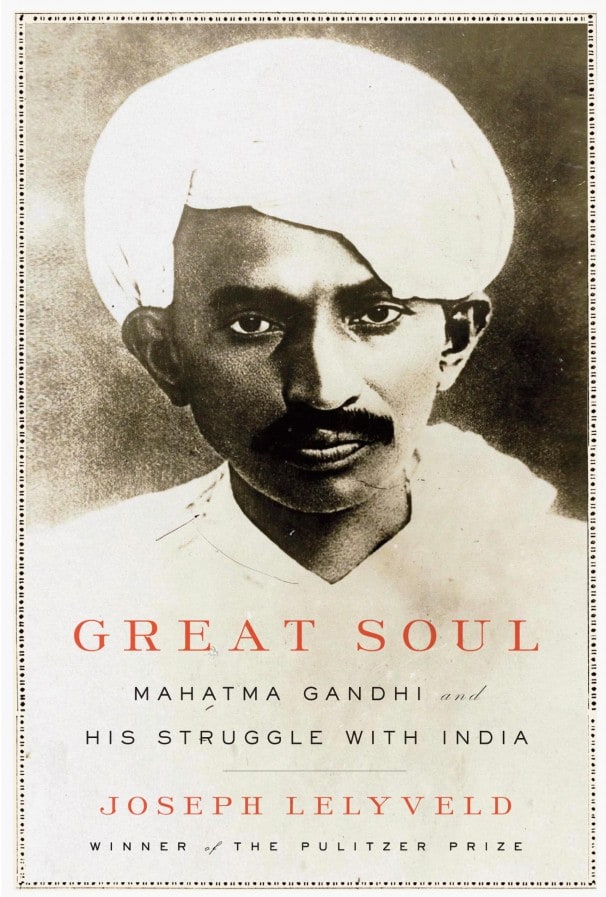

Book Review: Joseph Lelyveld’s Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India

Dustwrapper illustration courtesy Knopf; aaknopf.com

There is an old Indian saying that could very well have been intended for Gandhi: “There’s no one more difficult to live with than a saint.” As portrayed in Joseph Lelyveld’s biography (1) Gandhi was indeed a difficult “saint”, husband, and father. He told his wife and children many times that community came first, and often lived apart from them, sometimes for years on end. His vow of celibacy (brahmacharya), he writes in his Autobiography, was taken in agreement with his wife, after he had already decided on it. When his second son Manilal wanted to marry, as Joseph Lelyveld reports, Gandhi was quite “crotchety” about it, inveighing that he could not “imagine a thing as ugly as the intercourse of man and woman,” not precisely the sort of remark one would hope a father would make to a son anticipating a wedding night. The eldest son, Harilal was unstable, alcoholic, and was accused of embezzling. In the 1930s he converted to Islam, only six months later to reconvert to Hinduism, as if torn between defying or pleasing his father. Gandhi surely must bear some responsibility for his son’s dysfunction.

Gandhi’s attitude towards nonviolence also has its contradictions. If from the beginning of his career as a lawyer in South Africa he was committed to nonviolent resistance, that is, satyagraha, persistence in the truth, he also in South Africa held the rank of lieutenant colonel in the British militia, if as a noncombatant. He famously wrote, “Where there is a choice only between cowardice and violence I would advise violence.” And later he was also to say, “I would risk violence a thousand times rather than the emasculation of a whole race.” Lelyveld questions whether Gandhi’s numerous satyagraha campaigns had any lasting effect. His attempts to change the plight of the untouchables, his efforts to prevent the division of India and violence between Muslims and Hindus, were largely unsuccessful. Many scholars have argued that satyagraha was only one of many factors that led to Indian independence. Was the idea of nonviolence a greater achievement than any result?

Gandhi is an elusive subject for study. Nehru was to express his exasperation. “There is something unknown about you (Gandhi) which I cannot understand. It fills me with apprehension.” Of course, the key word is “apprehension.” In his biography Lelyveld makes us well aware of what he calls “contradictions,” although to call it a biography is perhaps a misnomer. Lelyveld was the New York Times correspondent in both South Africa and India, and he begins his book with Gandhi’s arrival in Durban in 1893, when Gandhi was 23, thus ignoring his childhood, childhood marriage, and the formative years in London influenced by his encounter with the spiritualist movement and dealt with so brilliantly in Kathryn Tidrick’s biography. (2) But Lelyveld’s is certainly one of the better accounts we have of Gandhi’s South Africa years, and his research into Gandhi’s years in India is comprehensive. He is as informed about Indian politics as anyone, both its history and present formations, and has considerable insight into Gandhi’s campaign to change the Indian caste system. On partition too he adds great clarity to Byzantine issues, often dealing with the complexities in carefully crafted and written summaries that will prove helpful to students and specialists.

Great Soul also challenges us to form opinions about other controversial areas of Gandhi’s life. Much press has been given to Lelyveld’s discussion of Gandhi’s “homoerotic” relationship with Herman Kallenbach, based on the recently released correspondence from Gandhi to Kallenbach. Much of Kallenbach’s side of the correspondence has been lost. Lelyveld indicates that there is no evidence of a physical relationship, but he does not delineate the chronology carefully enough to avoid insinuation, and compounds it by using such words as “couple” and “cohabit” to describe their friendship. Gandhi first met Kallenbach in 1903, but the friendship was not close until 1907 when Gandhi decided to share a house with Kallenbach, an arrangement that lasted until 1910. But Gandhi took his vow of celibacy in 1906 and there is no evidence that for the rest of his life he ever broke it, despite in his seventies his setting some rather public tests for himself. Kallenbach, also a nonviolence activist, professed his celibacy at the same time as Gandhi.

Gandhi’s vow of celibacy was based on the Hindu belief that sublimated sexual energy could be harnessed for positive, spiritual uses. Lelyveld does not adequately consider the transformational possibilities of sublimation and celibacy, or its effect on the friendship with Kallenbach. His book does not take Gandhi on his own, Hindu terms. Western sexual identity labels have previously been applied to Gandhi. Psychoanalyst Erik H. Erikson, in 1964, described Gandhi as bisexual, and Lelyveld’s book would seem to lend proof to this. Erikson wrote, “But I wonder whether there has ever been another political leader who has almost prided himself on being half man and half woman. (Gandhi) tried to make himself the representative of that bisexuality in a combination of autocratic malehood and enveloping maternalism.” (3) Yet, as many have said, it can be equally argued that renunciation was the key to understanding Gandhi. Certainly, he considered his vow of celibacy essential to his life as a nonviolence activist. Did celibacy free Gandhi to cultivate a passionate friendship with Kallenbach? Is there a transcendent, liberating potential to (freely chosen) celibacy? Even if we were to accept Gandhi’s bisexual or homoerotic sides would it add or detract from his stature or humanity?

Lelyveld also suggests other matters for further scrutiny. He reminds us, for example, of the Christian influences on Gandhi, of Tolstoy’s Christian anarchism, and the Sermon on the Mount, but also G. K. Chesterton’s political philosophy, which has not been adequately acknowledged. Gandhi has also had a reverse influence on Christian leaders. Martin Luther King Jr., Dorothy Day, Nelson Mandela, and countless others have found in Gandhian nonviolence a natural affinity.

Lelyveld does not end, as we might expect, with a summation of Gandhi’s importance. His book was written prior to the Arab Spring and the Occupy Movement having highlighted once again the force and relevance of Gandhian nonviolence, as interpreted in the contemporary writings of Gene Sharp and others. Lelyveld does remind us that few 20th century figures have been written about as much as Gandhi. Indeed, it seems as if there was someone with Gandhi every second of his life, not just to accompany him but also to write it all down minute by minute. On the one hand it means that there are as many opinions about events in Gandhi’s life as there are books about those events. A surfeit of information need not make a truth, or for that matter understanding. If one were to ask for a reliable, short account of Gandhi’s life then Douglas Allen’s insightful contribution to the Critical Lives series will suffice. (4) If one wants a full study then Judith M. Brown’s two-volume biography is often cited as “the best”. (5) But if you wish to have your views on Gandhi challenged and sharpened, and wish an account free of sentimentality and large on the Mahatma’s “contradictions”, then Joseph Lelyveld’s book commends itself to a wide readership.

Endnotes:

(1) Joseph Lelyveld, Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India, New York: Knopf, 2011.

(2) Kathryn Tidrick, Gandhi: A Political and Spiritual Life, London: Tauris, 2006.

(3) Erik H. Erikson, Gandhi’s Truth: On the Origins of Militant Nonviolence, New York: Norton, 1969; see especially pp. 402-6.

(4) Douglas Allen, Mahatma Gandhi, London: Reaktion Books, 2011.

(5) Judith M. Brown, Gandhi’s Rise to Power: Indian Politics 1915-1922, London: Cambridge University Press, 1972; and Gandhi and Civil Disobedience: The Mahatma in Indian Politics 1928-1934, London: Cambridge University Press, 1977. In some chapters in both volumes Brown has done such extensive research that she can follow Gandhi’s life day by day.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Joseph Geraci is the Director of the Satyagraha Foundation for Nonviolence Studies in Amsterdam and Editor of our website. Please access his other articles by clicking on his byline or via our Author Archives page.