Author Archive: Jim Forest

Since the early 1960s JIM FOREST has been one of the foremost leaders in the peace and nonviolent movements. He was the editor of

The Catholic Worker newspaper, and cofounder of the Catholic Peace Fellowship; Vietnam program coordinator for Fellowship of Reconciliation, and editor of

Fellowship magazine; secretary general of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation; and more recently founder and director of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship and editor of the Orthodox journal,

Communion. His many books include

All is Grace: a Biography of Dorothy Day and

Living With Wisdom: A Biography of Thomas Merton.

His own website has a list of his publications, and more of his essays.

by Dyllan Taxman

A drawing of Jim Forest in prison made by his son Ben, age six at the time, for his Sunday School class.

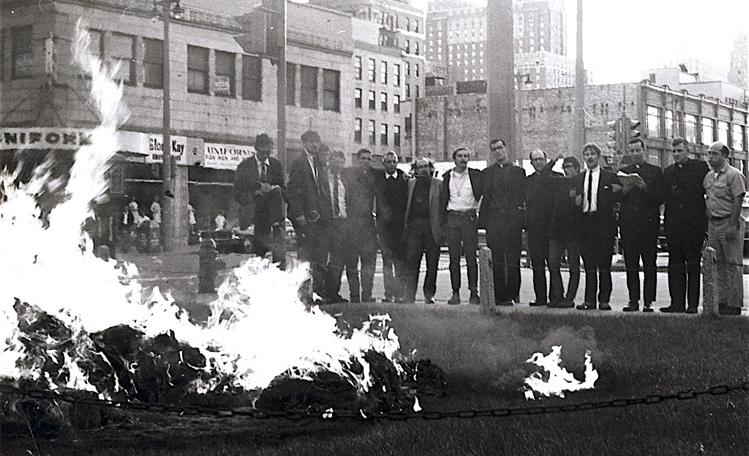

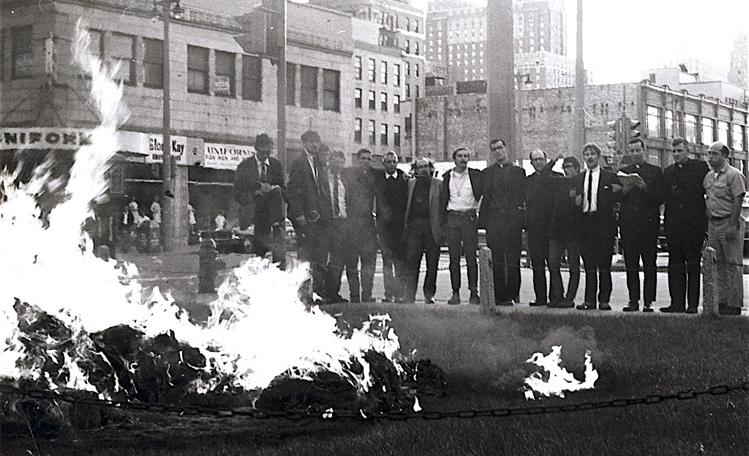

Editor’s Preface: Dyllan Taxman, an 8th grade student in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, was doing a research project for his history class and decided to look into an act of civil disobedience that had taken place in his city in September 1968. As Jim Forest has written, “The Vietnam War was raging. A group of fourteen people broke into nine draft boards that had offices side by side in a Milwaukee office building, put the main files into burlap bags, then burned the papers with homemade napalm in a small park in front of the office building while reading aloud from the Gospel. We awaited arrest, were jailed for a month, freed on bail, then tried the following year, after which we went to prison for more than a year; for most of us it was 13 months.” The interview was conducted in February 2006. Please see the note at the end for further information. JG

Dyllan Taxman: What made you do this?

Jim Forest: I had been in the military myself so didn’t have to worry about the draft, but as a draft counselor (a big part of my work with the Catholic Peace Fellowship) I was painfully aware of how thousands of young people were being forced to do military service in an unjust war about which they knew little or nothing, or even opposed. Anyone who knew the conditions for a just war could see this war did not qualify.

Read the rest of this article »

by Jim Forest

Photograph of the Milwaukee 14 courtesy Jim Forest; details at the end of the article.

Editor’s Preface: Tactics define a protest, whether violent or nonviolent. They have been and are a matter of controversy and heated discussion within movements, as in the recent Occupy. Indeed, some would define nonviolence as a tactic, a definition not accepted by all. In the Catonsville Nine and the Milwaukee 14 protests the burning of draft files was seen by some as a justified means towards ending the Vietnam War, while others such as Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton saw it, at the very least, as a dangerous blurring of the line between violence and nonviolence. Jim Forest is here adding his word to this debate. We have also posted other articles concerning the definition of nonviolent tactics, especially Dorothy Day’s famous article, “Dan Berrigan in Rochester”, and the book review at this link of a recent history of the Catonsville Nine, which quotes Merton’s famous warning. JG

I was one of the Milwaukee 14, a group that burned draft records in 1968. This was the action that followed the Catonsville Nine. The discussion of Plowshares-style property damage and destruction in the November issue of The Catholic Agitator really got me thinking. One of the essential elements in property destruction actions is secrecy. If you tell them you’re coming, they won’t let you in. It’s that simple. The only way around it is to take pains not to be expected. You are obliged to be secretive. There are events in life where secrecy is necessary, even contexts in which life-saving actions are difficult or even impossible unless there is secrecy. For example here in Holland, my home since 1977, you had to be highly secretive about the people you were hiding during the period of German occupation.

Read the rest of this article »

by Jim Forest

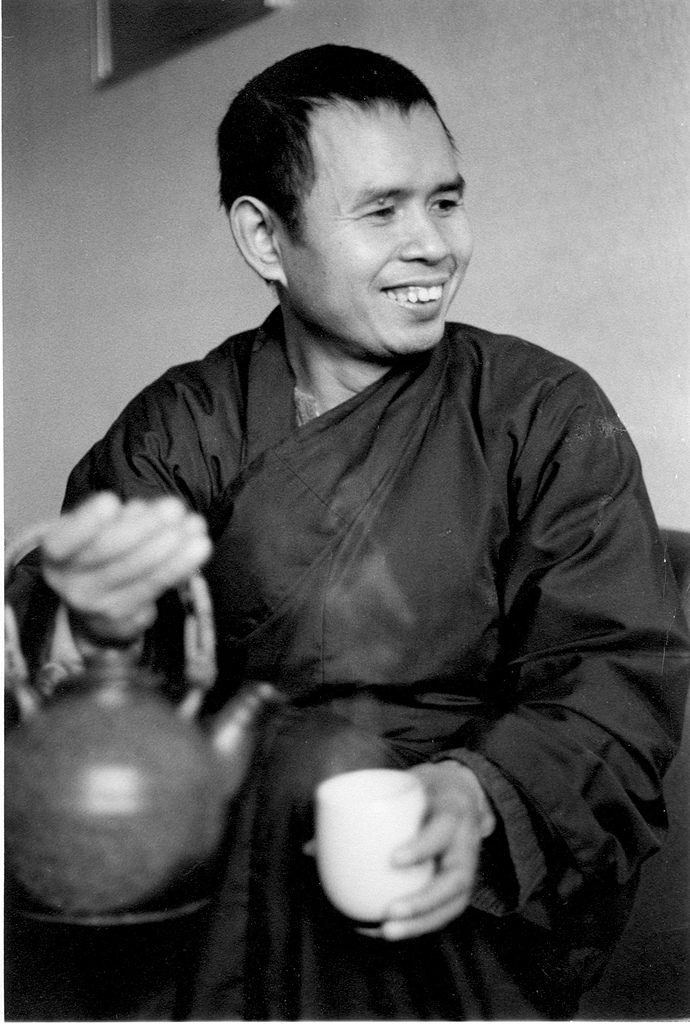

Thomas Merton; photograph by John Howard Griffin.

This is the text of the annual Oakham lecture, given in April 2012 at the meeting of the Thomas Merton Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Oakham School, England.

What initially put Merton on the world map was the publication in 1948 of his autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain. It was an account of growing up on both sides of the Atlantic (part of his adolescence was spent here at Oakham), what drew him to become a Catholic as a young adult, and finally what led him, in 1941, to become a Trappist monk at a monastery in rural Kentucky, Our Lady of Gethsemani. He was only 33 years old when the book appeared. To his publisher’s amazement, it became an instant bestseller. For many people, it was truly a life-changing book. I have lost count of how many copies of the book have been printed in English and other languages in the past 64 years, but we’re talking about millions.

Merton was and remains a controversial figure. Though he was a member of a monastic order well known for silence and for its distance from worldly affairs, Merton was outspoken on various topics that many regard as very worldly affairs. Merton disagreed. He was a critic of a Christianity in which religious identity is submerged in national or racial identity and life tidily divided between religious and ordinary existence.

Read the rest of this article »

by Jim Forest

Dorothy Day in her room at the CW Farm. Tivoli, New York; c. 1970; photo by Bob Fitch

I first met Dorothy Day a few days before Christmas in 1960 while on leave from the U.S. Navy. After reading copies of The Catholic Worker that I had found in my parish library, and then reading Dorothy’s autobiography, The Long Loneliness, I decided to visit the community she had founded. I was based not so far away, in Washington, DC.

Arriving in Manhattan for that first visit, I made my way to Saint Joseph’s House — then in a loft on Spring Street, on the north edge of Little Italy in the Lower East Side of New York City. Discovering that it was moving day, I joined in helping carry boxes from an upstairs loft to a three-storey brick building at 175 Chrystie Street, a few blocks to the east. Jack Baker, one of the other people assisting with the move that day, invited me to stay in his apartment in the same neighborhood. A few days later I visited the community’s rural outpost on Staten Island, the Peter Maurin Farm. Crossing Upper New York Harbor by ferry, I made my way to an old farmhouse on a rural road just north of Pleasant Plains near the island’s southern tip. In its large, faded dining room, I found half-a-dozen people, Dorothy among them, gathered around a pot of tea at one end of the dining room table.

Read the rest of this article »

by Jim Forest & Nancy Forest

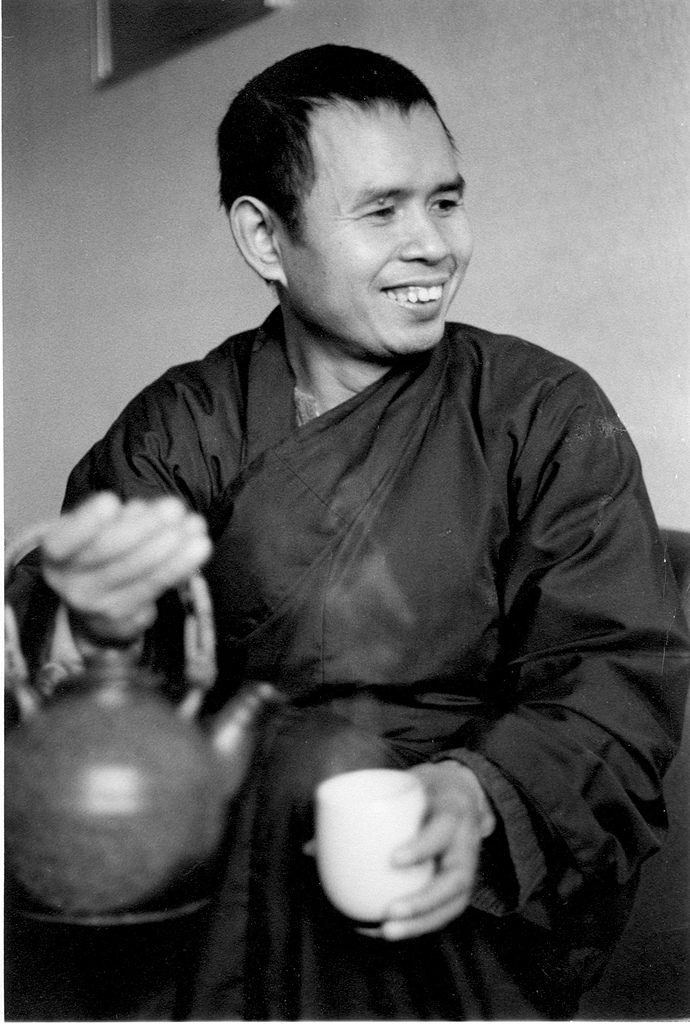

Original gelatin silver print photo by Jim Forest c. 1970.

I traveled and also at times lived with Thich Nhat Hanh in the late sixties through the seventies. Here are extracts from various letters in which Nancy and I relate a few stories about him. In these passages Nhat Hanh is sometimes called “Thay”, the Vietnamese word for teacher.

I sometimes think of an evening with Vietnamese friends in a cramped apartment in the outskirts of Paris in the early 1970s. At the heart of the community was the poet and Zen master, Thich Nhat Hanh. An interesting discussion was going on in the living room, but I had been given the task that evening of doing the washing up. The pots, pans and dishes seemed to reach half way to the ceiling on the counter of the sink in that closet-sized kitchen. I felt really annoyed. I was stuck with an infinity of dirty dishes while a great conversation was happening just out of earshot in the living room.

Somehow Nhat Hanh picked up on my irritation. Suddenly he was standing next to me. “Jim,” he asked, “what is the best way to wash the dishes?” I knew I was suddenly facing one of those very tricky Zen questions. I tried to think what would be a good Zen answer, but all I could come up with was, “You should wash the dishes to get them clean.” “No,” said Nhat Hanh. “You should wash the dishes to wash the dishes.” I’ve been mulling over that answer ever since — more than three decades of mulling.

Read the rest of this article »