Recollections of Thich Nhat Hanh: Being Peace

by Jim Forest & Nancy Forest

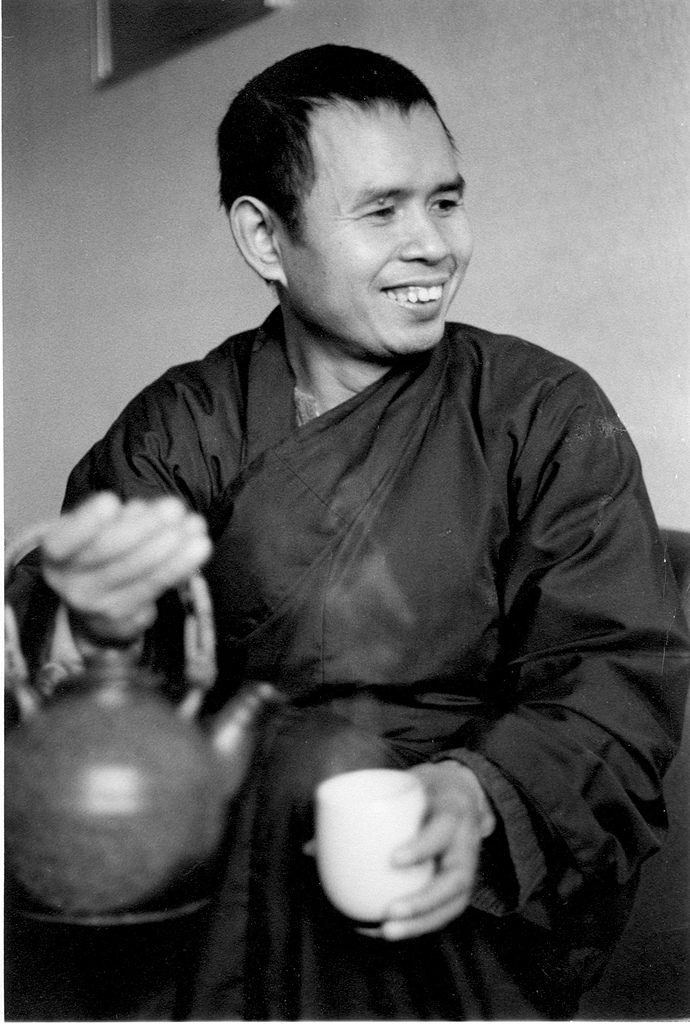

I traveled and also at times lived with Thich Nhat Hanh in the late sixties through the seventies. Here are extracts from various letters in which Nancy and I relate a few stories about him. In these passages Nhat Hanh is sometimes called “Thay”, the Vietnamese word for teacher.

I sometimes think of an evening with Vietnamese friends in a cramped apartment in the outskirts of Paris in the early 1970s. At the heart of the community was the poet and Zen master, Thich Nhat Hanh. An interesting discussion was going on in the living room, but I had been given the task that evening of doing the washing up. The pots, pans and dishes seemed to reach half way to the ceiling on the counter of the sink in that closet-sized kitchen. I felt really annoyed. I was stuck with an infinity of dirty dishes while a great conversation was happening just out of earshot in the living room.

Somehow Nhat Hanh picked up on my irritation. Suddenly he was standing next to me. “Jim,” he asked, “what is the best way to wash the dishes?” I knew I was suddenly facing one of those very tricky Zen questions. I tried to think what would be a good Zen answer, but all I could come up with was, “You should wash the dishes to get them clean.” “No,” said Nhat Hanh. “You should wash the dishes to wash the dishes.” I’ve been mulling over that answer ever since — more than three decades of mulling.

But what he said next was instantly helpful: “You should wash each dish as if it were the baby Jesus.” That sentence was a flash of lightning. While I still mostly wash the dishes to get them clean, every now and then I find I am, just for a passing moment, washing the baby Jesus. And when that happens, though I haven’t gone anywhere, it’s something like reaching the Mount of the Beatitudes after a very long walk.

In correspondence with a friend not long ago, I was reminded of this one: I recall going with Nhat Hanh to one of the Paris airports to pick up a volunteer who was arriving from America. On the way back, the volunteer stressed how dedicated a vegetarian she was and how good it was to be with people who were such committed vegetarians. Passing by the shop of a poultry butcher in Paris, Nhat Hanh asked to stop. He went inside and bought a chicken, which we ate that night for supper at our apartment in Sceaux. It’s the only time I know of when Nhat Hanh ate meat.

Another story: I often think about how Thich Nhat Hanh uses the image of one river/two shores as a way of attacking dualistic perception: Standing on a river bank, I see two shores, the shore I am standing on and the shore facing me, on the other side of the river. Two shores — you see them with your own eyes — two! But in reality there is only one shore. If I walk from where I stand to the source of the river and continue round that point, the “other side” becomes this side — the two-ness was created only by bending it. In time I will be on the opposite embankment, facing the spot where I was formerly standing, and I will have never crossed the stream to get there and I will never have changed shores.

Nhat Hanh and I were both friends of the Trappist monk and writer, Thomas Merton. They only met once, in May 1967. Merton immediately recognized Nhat Hanh as someone very like himself — a similar sense of humor, a similar outlook on the world and its wars, one of which was at the time killing many people in Vietnam. As the two monks talked, the different religious systems in which they were formed provided bridges. “Thich Nhat Hanh is my brother,” Merton wrote soon after their meeting. “He is more my brother than many who are nearer to me in race and nationality, because he and I see things exactly the same way.” When Merton asked Nhat Hanh what the war was doing to Vietnam, the Buddhist said simply, “Everything is destroyed.” This, Merton said to the monks in a talk he gave a few days later, was truly a monk’s answer, just three words revealing the essence of the situation.

Merton described the formation of young Buddhist monks in Vietnam and the fact that instruction in meditation doesn’t begin early. First comes a great deal of gardening and dish washing. “Before you can learn to meditate,” Nhat Hanh told Merton, “you have to learn how to close the door.” The monks to whom Merton told the story laughed — they were used to the reverberation of slamming doors as latecomers raced to the church.

And another: I recall an experience I had during the late sixties when I was accompanying Thich Nhat Hanh on a lecture trip in the United States. He was about to give a lecture at the University of Michigan on the war in Vietnam. Waiting for the elevator doors to open, I noticed my brown-robed companion gazing at the electric clock above the elevator doors. Then he said, “You know, Jim, a few hundred years ago it would not have been a clock, it would have been a crucifix.” He was right. The clock is a religious object in our world, one so powerful that it can depose another.

It was from Thich Nhat Hanh that I first became aware of walking as an opportunity to repair the damaged connection between the physical and the spiritual.

In the late sixties, he asked me to accompany him on his lecture trips in the United States. He spoke to audiences about Vietnamese culture and what the war looked like to ordinary Vietnamese people. At times he also spoke about the monastic vocation and meditation.

In conversation, Nhat Hanh sometimes spoke of the importance of what he called “mindful breathing,” a phrase that seemed quite odd to me at first. Yet I was aware that his walking was somehow different than mine and could imagine this might have something to do with his way of breathing. Even if we were late for an appointment, he walked in an attentive, unhurried way.

It wasn’t until we climbed the steps to my sixth floor apartment in Manhattan that I began to take his example to heart. Though in my late twenties and very fit, I was out of breath by the time I reached my front door. Nhat Hanh, on the other hand, seemed rested. I asked him how he did that. “You have to learn how to breathe while you walk,” he replied. “Let’s go back to the bottom and walk up again. I will show you how to breathe while climbing stairs.” On the way back up, he quietly described how he was breathing. It wasn’t a difficult lesson. Linking slow, attentive breaths with taking the stairs made an astonishing difference. The climb took one or two minutes longer, but when I reached my door I found myself refreshed instead of depleted.

In the seventies, I spent time in France with Nhat Hanh on a yearly basis. He was better known then; his home had become for many people a center of pilgrimage. One of the things I found him teaching was his method of attentive walking. Once a day, all his guests would set off in a silent procession led by him. The walk was prefaced with his advice that we practice slow, mindful breathing while at the same time being aware of each footstep, seeing each moment of contact between foot and earth as a prayer for peace. We went single file, moving slowly, deeply aware of the texture of the earth and grass, the scent of the air, the movement of leaves in the trees, the sound of insects and birds. Many times as I walked I was reminded of the words of Jesus: “You must be like little children to enter the kingdom of heaven.” Such attentive walking was a return to the hyper-alertness of childhood.

Mindful breathing connected with mindful walking gradually becomes normal. It is then a small step to connect walking and breathing with prayer.

by Nancy Forest

Here are some recollections I’d like to share.

I came to the Netherlands in April of 1982 with my daughter Caitlan, who was five years old at the time. Jim and I were married shortly after that. We had been friends for many years in the US. Both of us worked together at the headquarters of the Fellowship of Reconciliation in Nyack, New York, and Jim moved to Holland in 1977 to serve as general secretary of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation (IFOR). We had kept in touch during those five years. Jim was Cait’s godfather.

Shortly after I had moved here, Jim told me Thich Nhat Hanh would be coming to Alkmaar to visit. I had never met Nhat Hanh, but of course I had heard a great deal about him, and I knew how close Jim and Nhat Hanh had been over the years. Jim said Nhat Hanh would be coming to our house, and that the IFOR staff would be coming over as well to meet with him.

It was a beautiful day in May. First the staff arrived and took seats in our living room, then Nhat Hanh himself arrived, dressed in his brown robe. A hush fell over the staff members, and everyone was apparently in awe of this man. I remember feeling nervous that he was coming to our house, nervous about hosting this event. After he had sat down, the room fell silent and a sort of Zen silence fell on the room. It was hard for me to tell what to make of the atmosphere in the living room that day, but it made me uncomfortable.

In the meantime, Cait, who had just been given her first bicycle and was practicing riding it in the parking lot behind our house, kept running in to tell me how far she was advancing. So you have this room full of awestruck adults sitting there with what appeared to me glazed looks on their faces, and my little daughter running in, breathless with excitement.

After Nhat Hanh finished speaking with the staff, Jim came up to me and told me he had invited him to dinner. This was a little more than I could handle. I went into the kitchen at the back of the house and started chopping vegetables. I remember feeling that I really had to get out of that living room, that there was something definitely weird about what was going on there. It didn’t feel genuine, while the vegetables were certainly genuine and so was Cait.

After a few minutes, Nhat Hanh came into the kitchen and, almost effortlessly, started helping me with the vegetables. I think he just started talking to me in the most ordinary way. He ended up telling me how to make rice balls; how to grind the sesame seeds in a coffee grinder, to make the balls with sticky rice and to roll them in the ground sesame seeds. It was lots of fun and I remember laughing with him. The artificial Zen atmosphere was completely absent. Cait kept coming in, and Nhat Hanh was delighted with her.

This was my first Zen lesson.

What follows are my notes of a conversation with Thich Nhat Hanh on August 21, 1984 at Plum Village, near Ste Fois la Grande in the south of France, I found him outside sitting on a stone. He had permitted me to call him Thay, the Vietnamese word for Teacher.

Nancy Forest: Do you have a moment to talk?

Thay: Yes, please. Sit here on a stone.

NF: I’ve felt rather out of it here. I’m not a person from one of the Zen Centers, and I’m not an old friend, like Jim.

Thay: (very emphatically) No, no! You are wrong. Maybe you are better than Jim!

NF: (I tell him my “North Pole” experience — how, when I was young, I had a profound experience of standing at the point on the globe where all lines converge and intersect — an overwhelming experience of being at the absolute Center.)

Thay: It’s true we are each, as you say, like the North Pole. (He takes a stick and places it at the edge of his stone.) We are each on the edge. We are each separate, and each one of us has everyone within us.

NF: How can that be?

Thay: (He holds up a leaf.) As this leaf holds within it everything – all the sun, all water, all earth.

NF: But it also makes you realize we do everything alone. Everything, every step, alone. Walk through life alone. Die alone.

Thay: Yes. I told the people in the Zen Centers in America, “Meditation is a personal matter!” (He smiles.) That means meditation is an exercise in being alone, in realizing what it is to be alone. There is a story in Zen Buddhism about a monk. His name was (pause), “The Monk Who Was Alone.” He did everything alone: eat alone, wash dishes alone; everything. They said to him, “Why do you do everything alone?” He said, “Because that is the way we are.”

NF: (I tell him how, lately, I’ve been reading so many things which all seem to pertain to one event. How I pick up a book or read an article, and it all connects. I tell him at first I thought it was a coincidence that so much of what I read is connected.)

Thay: (Smiles and shakes his head.) It’s no coincidence.

NF: I’ve read some of Thomas Merton. And about the Hasidic Jews. And the story of the Fall in the Bible, Adam and Eve. About how, before the Fall, Eve just stood in her place, and walked in the garden. God had given them everything they needed, and it was all good. Eve didn’t know what evil was. Then when she was tempted to eat of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, she decided there wasn’t enough for her, just standing there – even though she didn’t have any idea what “evil” was. So by eating, she destroyed the garden. I’ve thought a lot about that here – walking slowly through the woods.

Thay: But you know – good and evil are just concepts. Maybe even the serpent was good, and the apple. All good. It’s like this stick. I can say, “This half is good, this half is evil.” They’re all concepts. Maybe Eve was even good after the Fall. You say “before the Fall – after the Fall.” It’s all the same.

NF: The Hasidic Jews always are dancing. It’s all holy, everything. But after Eve ate the apple, we don’t know if she really was able to know good from evil – we only know she was ashamed. (Thay smiles.) Merton said Eve wasn’t good before the Fall and bad afterwards. He said she was her True Self before the Fall and not her True Self afterwards.

Thay: And he also said, “Everything is Good.” (He smiles and stares at me) – and he said that in Bangkok! (Long pause.) You know, if you are really able to understand this, you can look at all the nuclear weapons and … (very long pause – his eyes scan the distance) … and smile.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Since the early 1960s Jim Forest has been one of the foremost leaders in the peace and nonviolent movements. He was the editor of the Catholic Worker newspaper, and co-founder of the Catholic Peace Fellowship; Vietnam program coordinator for Fellowship of Reconciliation, and editor of Fellowship magazine; secretary general of the International Fellowship of Reconciliation, and more recently founder and director of the Orthodox Peace Fellowship and editor of the Orthodox journal, Communion. He has received Notre Dame University’s Peacemaker Award, and the St. Marcellus Award from the Catholic Peace Fellowship. He is a prolific writer, having written the definite biography of Dorothy Day, All is Grace, and also spiritual works on icons and prayer. His bibliography is too extensive to list here, but his Wikipedia article provides further biographical and bibliographical information. We also strongly recommend Jim and Nancy’s website, for its extensive posting of his and her articles and his wonderful photographs.

Nancy Forest-Flier is a freelance Dutch-English translator and English language editor. She is a gifted essayist who has written on marriage, Russian literature, St. Paul, women, etc. Some of her essays are available on their website as is more information about her translations and work.