Martin Luther King Jr.’s Steps to Nonviolent Action

by John Dear

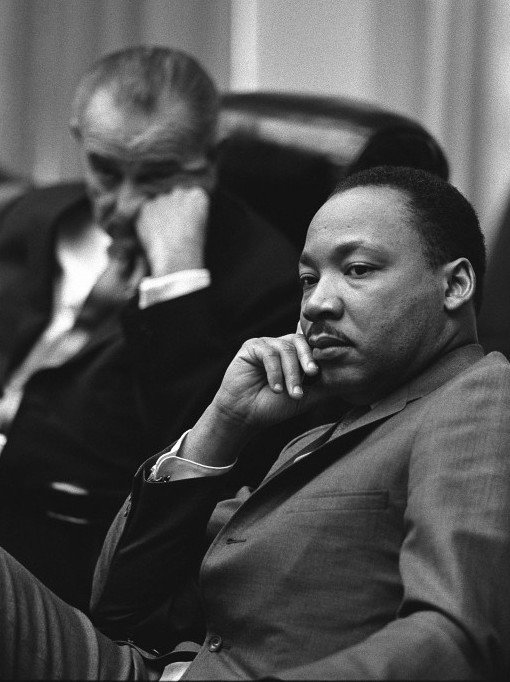

Dr. King with President Lyndon Johnson; photographer unknown; public domain image courtesy of commons.wikimedia.org

I’ve been reflecting on the principles of nonviolence, which Dr. Martin Luther King learned during the historic yearlong bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. After Rosa Parks refused to sit in the back of the bus, broke the segregation law, and was arrested on December 1, 1955, the African-American leadership in Montgomery famously chose young Rev. Dr. King to lead their campaign. He was an unknown quantity. Certainly no one expected him to emerge as a Moses-like tower of strength. No one imagined that he would invoke Gandhi’s method of nonviolent resistance in Christian language as the basis for the boycott. But from day one, he was a force to be reckoned with.

With the help of Bayard Rustin and Glenn Smiley of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, Dr. King articulated a methodology of nonviolence that still rings true. It’s an ethic of nonviolent resistance that’s also a strategy of hope, which can help us today in the thousands of Montgomery-like movements around the world, including environmentalism and the ongoing Arab Spring.

Dr. King outlined his way of nonviolence in his 1958 account of the Montgomery movement, Stride Toward Freedom (New York: Harper and Row, pp. 83-88). There he tells the story of the movement and his own personal journey, from which we can extrapolate his six nonviolence principles. Dr. King lived and taught these essential ingredients of active nonviolence until the day he died. (For an excellent commentary on them, I recommend Roots of Resistance: The Nonviolent Ethic of Martin Luther King, Jr., by William D. Watley, Valley Forge: Judson Press, 1985.)

These fundamental principles of nonviolent action, along with six steps outlined later in the article, make up Dr. King’s “to do” list:

First: Nonviolence is the way of the strong.

Nonviolence is not for the cowardly, the weak, the passive, the apathetic, or the fearful. “Nonviolent resistance does resist,” he wrote. “It is not a method of stagnant passivity. While the nonviolent resister is passive in the sense that he is not physically aggressive toward his opponent, his mind and emotions are always active, constantly seeking to persuade his opponent that he is wrong. The method is passive physically, but strongly active spiritually. It is not passive non-resistance to evil; it is active nonviolent resistance to evil.”

Second: The goal of nonviolence is redemption and reconciliation.

“Nonviolence does not seek to defeat or humiliate the opponent but to win friendship and understanding,” King teaches. “The nonviolent resister must often express his protest through non-cooperation or boycotts, but he realizes that these are not ends themselves; they are merely means to awaken a sense of moral shame in the opponent. . . . The aftermath of nonviolence is the creation of the beloved community, while the aftermath of violence is tragic bitterness.”

Third: Nonviolence seeks to defeat evil, not people.

Nonviolence is directed “against forces of evil rather than against persons who happen to be doing the evil. It is evil that the nonviolent resister seeks to defeat, not the persons victimized by evil.” As Watley writes, in the book cited above, “Not only did King depersonalize the goal of nonviolence by defining it in terms of reconciliation rather than the defeat of the opponent, but he also depersonalized the target of the nonviolent resister’s attack. The opponent for King is a symbol of a greater evil . . . The evildoers were victims of evil as much as were the individuals and communities that the evildoers oppressed.” In this thinking, King echoes St. Paul’s admonition that our struggle is ultimately not against particular people, but against systems, “the principalities and powers.”

Fourth: Nonviolence includes a willingness to accept suffering without retaliation, to accept blows from the opponent without striking back.

King writes, “The nonviolent resister is willing to accept violence if necessary, but never to inflict it. Unearned suffering is redemptive. Suffering, the nonviolent resister realizes, has tremendous educational and transforming possibilities.” That’s a tough pill to swallow but King insists that there is power in the acceptance of unearned suffering love, as the nonviolent resister Jesus showed on Calvary and Dr. King himself showed in his own life and death.

In Stride Toward Freedom (p. 194) King urged nonviolent resisters to follow the example of Gandhi:

“We will match your capacity to inflict suffering with our capacity to endure suffering. We will meet your physical force with soul force. We will not hate you, but we cannot in all good conscience obey your unjust laws. Do to us what you will and we will still love you. Bomb our homes and threaten our children; send your hooded perpetrators of violence into our communities and drag us out on some wayside road, beating us and leaving us half dead, and we will still love you. But we will soon wear you down by our capacity to suffer. And in winning our freedom we will so appeal to your heart and conscience that we will win you over in the process.”

Fifth: Nonviolence avoids not only external physical violence but also internal violence of spirit.

Nonviolence is the practice of agape/love through action. “The nonviolent resister not only refuses to shoot his opponent; he also refuses to hate him. At the center of nonviolence stands the principle of love.” Cutting off the chain of hate “can only be done by projecting the ethic of love to the center of our lives.” Love means “understanding, redemptive good will toward all people.” For King, this agape/love is the power of God working within us, as Watley also explains. That is why King could exhort us to the highest possible, unconditional, universal, all-encompassing love. King the preacher believed that God worked through us when we used the weapon of nonviolent love.

Sixth: Nonviolence is based on the conviction that the universe is on the side of justice.

“The believer in nonviolence has deep faith in the future,” King writes. “He knows that in his struggle for justice he has cosmic companionship. There is a creative force in this universe that works to bring the disconnected aspects of reality into a harmonious whole.” King’s philosophy, spirituality, theology and methodology were rooted in hope.

These core principles explain why, for King, nonviolence was “the morally excellent way.” As he boldly expanded his campaign from Montgomery to Atlanta, Albany, and eventually Birmingham, he demonstrated six basic steps of nonviolent action that could be applied to any nonviolent movement for social change.

As explained in Active Nonviolence (Vol. I, ed. by Richard Deats, The Fellowship of Reconciliation, 1991), every campaign of nonviolence usually includes the following 6 stages, and they are worth our consideration:

1. Information gathering.

We need to do our homework, and learn everything we can about the issue, problem or injustice so that we become experts on the topic.

2. Education.

Then we do our best to inform everyone, including the opposition, about the issue, and use every form of media to educate the population.

3. Personal commitment.

As we engage in the public struggle for nonviolent social change, we renew ourselves every day in the way of nonviolence. As we learn that nonviolent struggles take time, we commit ourselves to the long haul and do the hard inner work necessary to center ourselves in love and wisdom, and prepare ourselves for the possibility of rejection, arrest, jail or suffering for the cause.

4. Negotiations.

We try to engage our opponent, point out their injustice, propose a way out, and resolve the situation, using win-win strategies.

5. Direct action.

If necessary, we take nonviolent direct action to force the opponent to deal with the issue and resolve the injustice, using nonviolent means such as boycotts, marches, rallies, petitions, voting campaigns, and civil disobedience.

6. Reconciliation.

In the end, we try to reconcile with our opponents, even to become their friends (as Nelson Mandela demonstrated in South Africa), so that we all can begin to heal and move closer to the vision of the “beloved community.”

Dr. King’s principles and methodology of nonviolence outline a path to social change that still holds true. In his strategy, the ends are already present in the means; the seeds of a peaceful outcome can be found in our peaceful means. He argues that if we resist injustice through steadfast nonviolence and build a movement along these lines, we take the high ground as demonstrated in the lives of Jesus and Gandhi and can redeem society and create a new culture of nonviolence.

“May all who suffer oppression in this world reject the self-defeating method of retaliatory violence and choose the method that seeks to redeem,” Dr. King concluded. “Through using this method wisely and courageously we will emerge from the bleak and desolate midnight of ‘man’s inhumanity to man’ into the bright daybreak of freedom and justice.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: John Dear has been nominated five times for the Nobel Peace Prize, most notably in 2008 by Archbishop Desmond Tutu; but that does not tell a fraction of his story. One of the most prominent peace activists in the world, he has been arrested more than 75 times for peace and nonviolent protests. He was Executive Director of Fellowship of Reconciliation (1998-2001) and founder of the Bay Area Pax Christie. He has received several peace awards, including the Pacem in Terris Peace and Freedom Award 2010. He is a prolific writer. Among his works are: Disarming the Heart: Toward a Vow of Nonviolence; Our God Is Nonviolent: Witnesses in the Struggle for Peace and Justice; Seeds of Nonviolence; etc. We are very grateful to John Dear for permission to post this profound and important essay and recommend his website for a more extensive bibliography, and to read other of his articles, speeches, and sermons.