Gene Sharp Is No Utopian

Six years ago, Brian Martin (Professor of Social Science, University of Wollongong, Australia) wrote in the journal Peace and Change, “Whereas Gandhi was unsystematic in his observations and analyses, [Gene] Sharp is relentlessly thorough. Most distinctively so in his epic work, The Politics of Nonviolent Action, Sharp has had more influence on social activists than any other living theorist.”

I would go further. Gene has in my opinion done more for the building of peace than any person alive. This is because I consider the knowledge of how to fight for justice and social change without a resort to violence to be the most critical and essential component of building peace.

The history of nonviolent action is rich, diverse, and often overlooked. Despite historically significant, at times revolutionary, accomplishments over centuries and across continents, it is regrettably true that universities, social scientists, journalists and news media, diplomats, and policy makers often neglect to place a high priority on the study of the power and dynamics of nonviolent action. In many societies, including the United States, the history of their wars is taught, while the achievements of their nonviolent struggles are scarcely mentioned. Gene has done more to correct this deficit than any other single scholar or theoretician.

In 1973, Gene published the landmark three volume, The Politics of Nonviolent Action (known as the Politics, or the Trilogy), the most important and influential work in the spread of ideas about fighting with collective nonviolent action in the latter half of the 20th century. It represented both a quantitative and qualitative leap worldwide in the spread of knowledge on nonviolent struggle. This is where his famous 198 nonviolent methods first appeared.

The Politics shows power as the basis of nonviolent civil resistance, a means of engaging in conflicts. Perhaps most revealing is Gene’s dissection of how systems and governments must ensure for themselves a steady supply of political power and why the stock of power that sustains state authority is not possessed by its leaders—it is granted by the people, who can withdraw that power and cooperation. The Politics shows that nonviolent strategic action achieves its political objectives by altering the power configurations among groups or persons, allowing for social and political change.

His work cumulatively demonstrates that nonviolent struggle can lead to stable, long-term results, sometimes benefiting all the parties to a conflict—without bloodshed. Yet he makes clear that nonviolent action is not necessarily a choice based on principled nonviolence, idealism, or pacifism. By the 1970s, he had discredited the designation of nonviolent action as pacifism, when he found that he could count on two hands the number of cases out of 85 he had then studied in which the leadership of a nonviolent movement had been pacifist. This is important because movements need numbers, including people who reflect diverse creeds and backgrounds.

I cannot possibly mention all of Gene’s extraordinary contributions to our understanding of social and political power, and the nature and history of civil resistance. In some ways my favorite is his 1958 study that resulted from his time at the Institute of Philosophy and the History of Ideas in Oslo, Tyranny Could Not Quell Them. One can see in it his early and lasting quest for real-life experience as the essential basis for understanding how nonviolent action works and the building of its theory, which became his life’s work. It describes the details of the Norwegian teachers’ resistance under the Nazi occupation. Gene describes how Norwegians wore paper clips on their lapels as a sign of “keeping together”; in the classroom students began wearing necklaces and bracelets of linked paper clips. One teacher noticed his pupils wearing tiny potatoes on matchsticks in their lapels. The potatoes became larger with each passing day as a symbol that the anti-Nazi forces were on the rise.

We now have abundant documentation—from anecdotal reports, oral testimony, and news accounts—that Gene’s works have been influential and generative in many contemporary civil resistance struggles. In general, activist intellectuals and scholar organizers study his works and digest them; they then share the insights with participants and grassroots organizers.

From Dictatorship to Democracy, just 78 pages, was studied by the galvanizing group Otpor!, which led the successful nonviolent revolution in Serbia in 2000 against Slobodan Milosevic. After a Serbian NGO, the Center for Civic Initiatives, translated it into Serbian and distributed it, Otpor!’s members in 42 Serbian cities trained more than 1,000 activists in civil resistance in 1999 and 2000. The trainees may not have read Gene, but the people leading the workshops had read him. Otpor! went on to work with the leaders of Georgia’s Rose Revolution in 2003 and Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution, interpreting from Gene’s publications.

2011 has been a breakthrough year with the Arab Awakening. Accounts have been trickling out from Egypt, Syria, Tunisia, Yemen, and elsewhere of how the organizers and bloggers of these major democracy movements have turned to Gene’s works, some of which have been accessible in Arabic, Farsi, and Kurdish since 2003.

His writings are available, often downloadable, on the website of The Albert Einstein Institution. You’ll find Dictatorship to Democracy in 34 languages. The BBC has interviewed Gene several times, and has released a feature-length film about him, How to Start a Revolution. Oxford University Press has published Sharp’s Dictionary of Power and Struggle: Language of Civil Resistance in Conflicts, on which he worked for decades. In 2011 he was awarded the El-Hibri Peace Education Prize.

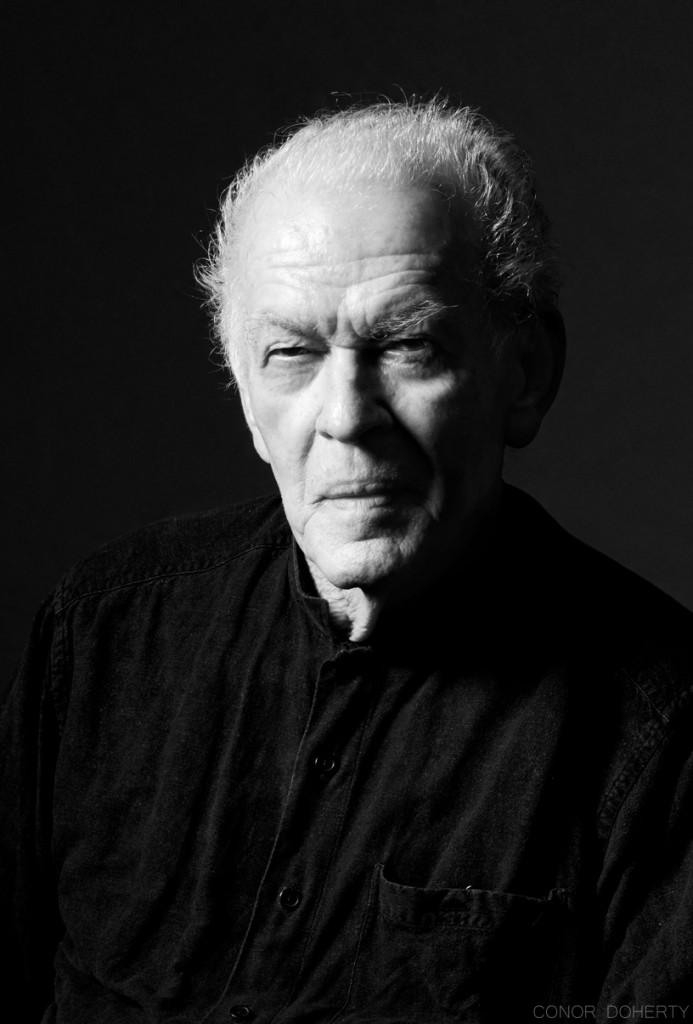

A word about Gene’s remarkable personal attributes, which are many, including his generosity of spirit, plain-spoken accessibility, and readiness to help leaders across the world. I want to mention two traits that are especially endearing: Gene is never in a hurry and is always patient.

Let me close by emphasizing what I believe to be the most alluring aspect of Gene’s lifelong body of work. He has been the most significant theoretician to analyze and advance nonviolent struggle as a credible and powerful means of engagement in conflicts. He has within the body of his work offered this viewpoint with intellectual integrity and credibility. It is based on years of immersion with the major thinkers in political theory, deep studies of dictatorships and totalitarian regimes, and analyses of actual cases of historic nonviolent struggles. Albert Einstein described Gene as a “born historian, in whose hands the various threads are held together and woven into a pattern from which a complete picture emerges.”

Gene has raised for humanity the important possibility that nonviolent action is a practical and effective method that might gradually and incrementally be substituted for violence and deadly conflict. Even while acknowledging the validity of armed force in policing and other defense needs, and recognizing that nonviolent action often interacts with other forms of power, in reading his works we can discern that civil resistance may be able to replace reliance on force in different issues and areas. It must, however, be organized around precise requirements and specific purposes, and embarked upon with serious study, preparation, planning, and strategic analysis. In his 1980 work, Social Power and Political Freedom, he shows us that replacing violent sanctions with nonviolent sanctions gradually, in a series of particular substitutions, is not utopian. To an extent not usually recognized, this is already taking place by degrees in various conflicts, sometimes affecting domestic policies and international relations. Nonviolent methods are built upon exact encounters in past and present actuality.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Gene Sharp held research appointments at Harvard University’s Center for International Affairs for more than thirty years. Among Sharp’s 14 books, his The Politics of Nonviolent Action (1973) is recognized as the definitive study of nonviolent struggle. In 1983 Sharp founded the Albert Einstein Institution in Boston where he currently serves as senior scholar. His best-known publication From Dictatorship to Democracy: A Conceptual Framework for Liberation (1993) has been published in 34 languages. In 2009 Dr. Sharp was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Mary Elizabeth King is professor of peace and conflict studies at the University for Peace and a Rothermere American Institute Fellow at the University of Oxford (UK). She is also distinguished scholar with the American University’s Center for Peacebuilding and Development, in Washington, D.C. She is the author of The New York Times on Emerging Democracies in Eastern Europe, A Quiet Revolution: The First Palestinian Intifada and Nonviolent Resistance, Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr.: The Power of Nonviolent Action, and Freedom Song: A Personal Story of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement. During the U.S. civil rights movement, she worked alongside Martin Luther King, Jr. (no relation), in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. She co-authored “Sex and Caste” with Casey Hayden, a 1966 article viewed by historians as tinder for second-wave feminism. For more articles by Dr. King, biographical information, et al. please consult her website.

This article was adapted from Mary Elizabeth King’s introduction of Gene Sharp, at the 2011 El-Hibri Peace Education Prize Laureate ceremony in Washington, D.C. Our thanks to wagingnonviolence.org for allowing us to share their posting of October 1, 2011.