The Organizer Cesar Chavez

by Dorothy Day

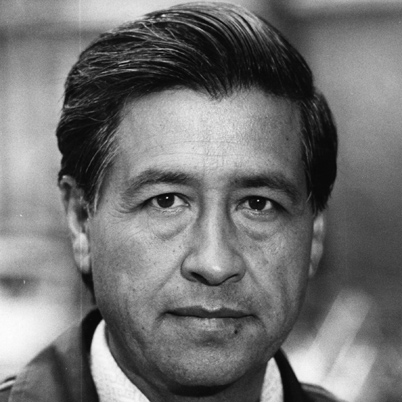

Cesar Chavez, c. 1965; photographer unknown

“Workers of the World, unite. You have nothing to lose but your chains!” This is one of those stirring slogans of the Marxists especially appealing to youth, no matter what kind of family they come from, upper, middle, or lower middle class. If it does not attract them to Marxism, it at least gives them a sense of community and relatedness to other sufferers and combats the sense of futility and frustration, which encompasses so many.

Cesar Chavez is the leader of the Delano California farm-workers who are on strike in an area which stretches for 400 miles and includes thousands of acres of grapes, tomatoes, apricots, cotton — all kinds of crops. This strike, which has been going on since last September, appeals to all the poor of the United States. Chavez uses the word commitment, a word much in style now. But he combines it with the idea of necessity, the irrevocable. “We are committed,” he says. “When you lose your car, then lose your home, you do not become less committed, but more. None of us has anything more to lose.”

The agricultural workers of this country have long been the most abandoned and forgotten. They have been neglected in all Social Security legislation. From the first issue of The Catholic Worker, down through the years, we have written about the Negroes working on the levees, about the dispossessed sharecroppers of Arkansas and Oklahoma, the Mexicans in the onion fields of Ohio and Michigan, in sugar beets in the middle Northwest, about those who work in the potato farms in Maine, Long Island and New Jersey, in the turpentine woods of the South, about the citrus pickers of Florida, the Delta Negroes now being dispossessed from the cotton fields, and now the present strikers in California. The Catholic Worker has dealt with these stories and I have personally visited these fields of struggle.

When the great acreage of farms controlled by the Campbell Soup people in New Jersey were followed by strike we urged boycott of these products and when the strike had been won and the years passed, Hisaye Yamamoto, (1) who lived with us on Peter Maurin Farm for years, went back to the area to interview her fellow Japanese who were by then working under greatly improved conditions.

The farm problem is a struggle through all the years of our lives, which has to do with Factories in the Fields, the title of a book of a generation past, written by Carey McWilliams present editor of The Nation (Boston: Little Brown, 1939). It is a struggle which involves the food problem of the world and the best way to handle it. It involves discussion of the population problem, and so encompasses the all absorbing needs of food and sex. It employs every nationality on West and East coasts, from far-off India and Pakistan, southeast Asia, as well as the Caribbean. It involves our own Negro and white Americans.

Over all these years there have been sporadic outbreaks among rural workers from coast to coast. It is only now the nationwide picture has become unified, under the leadership of a man of vision as well as of experience. We had a story about the strike in California in our January issue, written by a young CW reader who has been active there. Bob Callagy, of the Oakland Catholic Worker group, and number of other young families, are busy trucking food and clothing to the strikers. So this continuation of the story is to call attention to Cesar Chavez himself, and the interview I am basing it on is by Lisa Hobbs of the San Francisco Examiner and Chronicle of January 16.

Chavez was born in Texas March 31, 1927. His grandfather had homesteaded near Yuma in 1889 and had very rich land just off the Colorado River. Cesar and his four brothers and sisters were brought up there. They were taught the Catholic faith by their grandmother, the only member of the family who could read or write. When the depression came, crop prices failed, and taxes were raised (to care for the people put off the land and set to wandering with the crops or living in the cities). The water bills, a big item in the West, went unpaid, and the land was foreclosed. The grandparents and all the rest of the family then went West to California and worked in the fields, drifting from crop to crop.

Chavez himself only went as far as the 7th grade but read widely, biographies and history as well as the Bible. He discovered, he says, “that Paul was a great organizer who would go out and talk to the people right in their homes and be one of them.” He was doubtless impressed too with the fact that St. Paul was a worker, who earned his living by weaving tents from goat hair.

When Chavez was in his mid-twenties his organizing ability was recognized by the Community Service Organization, a statewide group supported by voluntary contributions to assist the Mexican American in citizenship and legal problems. He served as statewide organizer and after seven years experience was appointed executive director of the Los Angeles headquarters. After ten years of this kind of work, he went back to work in the fields and to organize. His wife Helen Fabela Chavez, mother of 8 children, was also born in Delano and so the present “revolution” is starting there.

Six years ago, when I drove out through Arizona and up the California Valley, I wrote of the lettuce strike around El Centro and told of meeting a young Italian priest whose family owned land, and the beginning of his interest in the problems of the workers. I wrote, too, of the CIO autoworkers’ attempts to organize around Stockton, and of Hank Anderson and Henry Van Dyke, whose reports showed vision for all of California.

Now Chavez has organized his National Farm Workers Association, which seems able to work side-by-side with the existing unions in the field. Since the strike started a bulletin has been published, attractively illustrated by Mexican worker artists. In the bulletin one finds indications of the larger purpose, which Cesar Chavez has in mind. The insistence on nonviolence, the emphasis on the religious and moral aspects of the strike, and the expression of hope and faith animated by love, make this strike different from any other I have ever written about.

Cesar Chavez also takes a national view, as the name of his association indicates (NFWA). What he hopes to do, to begin to do, is to change the face of agriculture in the Long Valley in California, up and down the coast, and on through the Southwest and South and up the East Coast. This vision is not that of an excited imagination, but a result of living for a lifetime with these problems, and the sense that God plays a hand in these events. “One must start somewhere. Delano is just the beginning but it cannot be all at once,” he says.

“But when it happens, when we win, it will be a very dramatic thing. We can point to the workers everywhere and say: ‘Remember Delano’.”

Endnote: (JG)

(1) Hisaye Yamamoto (1921 – 2011) is a Japanese American author, best known for her short story collection Seventeen Syllables and Other Stories (Latham, New York: Kitchen Table/Women of Color Press, 1988). Her work dealt forcefully with the plight of the Japanese immigrant in America, the disconnect between first and second generation immigrants, as well as the difficult role of women in society.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is from The Catholic Worker, February 1966, pp. 1, 6; courtesy of Marquette University and the staff of The Catholic Worker.