by Mary Elizabeth King

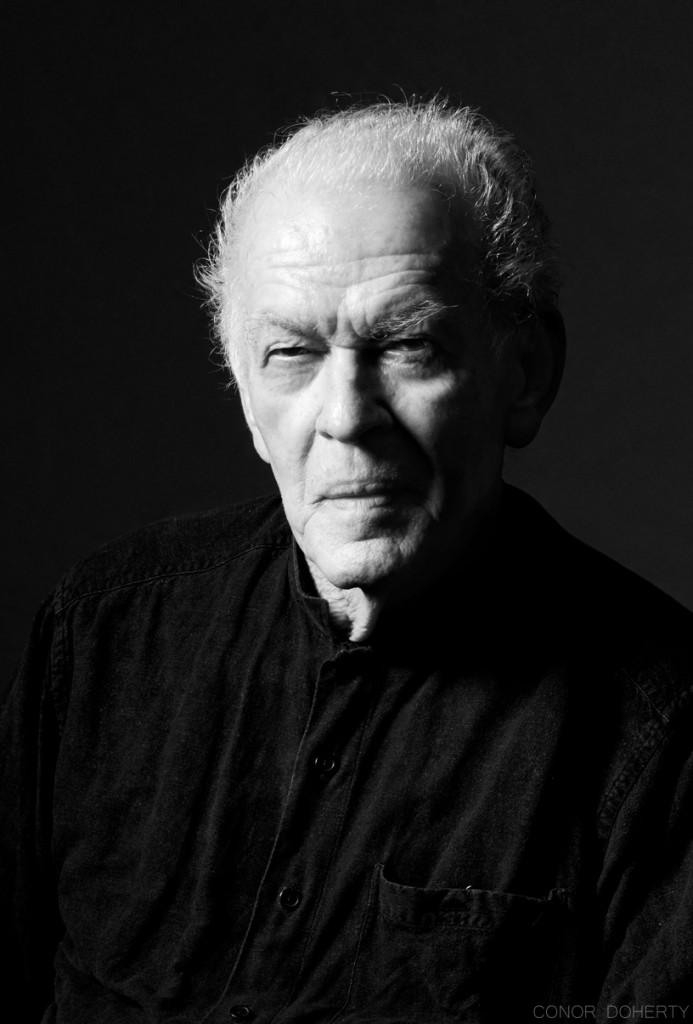

Portrait of Gene Sharp; photograph by Conor Doherty; courtesy of the photographer

Six years ago, Brian Martin (Professor of Social Science, University of Wollongong, Australia) wrote in the journal Peace and Change, “Whereas Gandhi was unsystematic in his observations and analyses, [Gene] Sharp is relentlessly thorough. Most distinctively so in his epic work, The Politics of Nonviolent Action, Sharp has had more influence on social activists than any other living theorist.”

I would go further. Gene has in my opinion done more for the building of peace than any person alive. This is because I consider the knowledge of how to fight for justice and social change without a resort to violence to be the most critical and essential component of building peace.

Read the rest of this article »

by Mary Elizabeth King

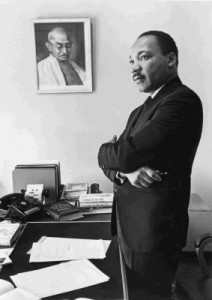

How does one learn nonviolent resistance? The same way that Martin Luther King Jr. did—by study, reading and interrogating seasoned tutors. King would eventually become the person most responsible for advancing and popularizing Gandhi’s ideas in the United States, by persuading black Americans to adapt the strategies used against British imperialism in India to their own struggles. Yet he was not the first to bring this knowledge from the subcontinent.

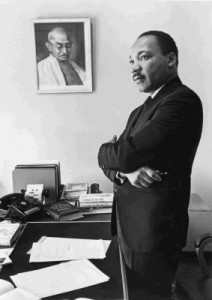

Martin Luther King, Jr. beside a picture of Gandhi; photograph © Bob Fitch

By the 1930s and 1940s, via ocean voyages and propeller airplanes, a constant flow of prominent black leaders was traveling to India. College presidents, professors, pastors and journalists journeyed to India to meet Gandhi and study how to forge mass struggle with nonviolent means. Returning to the United States, they wrote articles, preached, lectured and passed key documents from hand to hand for study by other black leaders. Historian Sudarshan Kapur has shown that the ideas of Gandhi were moving vigorously from India to the United States at that time, and the African American news media reported on the Indian independence struggle. Leaders in the black community talked about a “black Gandhi” for the United States. One woman called it “raising up a prophet,” which Kapur used as the title of his book.

While a student at Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, King was intrigued by reading Thoreau and Gandhi, yet had not actually studied Gandhi in depth. A friend, J. Pius Barbour, remembered the young seminarian arguing on behalf of Gandhian methods with a reckoning based on arithmetic—that any minority would be outnumbered if it turned to a policy of violence—rather than on principle.

Read the rest of this article »

by Mary Elizabeth King

Around the time that my book A Quiet Revolution was published in 2007, detailing the Palestinians’ use of nonviolent resistance, I recall that The Atlantic was publishing an article by Jeffrey Goldberg. In it, he asked, “Where are the Palestinian Gandhis and Martin Luther Kings?” — or words to this effect. Upon reading this, the question burned for me. How can historical reality be so ignored, and how can history be told in a way that is so one-sided?

The violent responses to Zionism have been assiduously documented. Yet in archives, newspapers, interviews and conversations, I found numerous uncelebrated Palestinian Gandhis and Kings. Indeed, I identified at least two dozen activist intellectuals who had worked openly for years to change Palestinian political thought — many of whom would be deported, jailed or otherwise compromised by the government of Israel for their efforts. More to the point, the 1987 intifada was only the latest manifestation of a Palestinian tradition of nonviolent resistance that goes back to the 1920s and 1930s. Similar oversights have occurred in the histories of peoples all over the world.

Read the rest of this article »

by Jim Forest

Thomas Merton; photograph by John Howard Griffin.

This is the text of the annual Oakham lecture, given in April 2012 at the meeting of the Thomas Merton Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Oakham School, England.

What initially put Merton on the world map was the publication in 1948 of his autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain. It was an account of growing up on both sides of the Atlantic (part of his adolescence was spent here at Oakham), what drew him to become a Catholic as a young adult, and finally what led him, in 1941, to become a Trappist monk at a monastery in rural Kentucky, Our Lady of Gethsemani. He was only 33 years old when the book appeared. To his publisher’s amazement, it became an instant bestseller. For many people, it was truly a life-changing book. I have lost count of how many copies of the book have been printed in English and other languages in the past 64 years, but we’re talking about millions.

Merton was and remains a controversial figure. Though he was a member of a monastic order well known for silence and for its distance from worldly affairs, Merton was outspoken on various topics that many regard as very worldly affairs. Merton disagreed. He was a critic of a Christianity in which religious identity is submerged in national or racial identity and life tidily divided between religious and ordinary existence.

Read the rest of this article »

by Jim Forest

Dorothy Day in her room at the CW Farm. Tivoli, New York; c. 1970; photo by Bob Fitch

I first met Dorothy Day a few days before Christmas in 1960 while on leave from the U.S. Navy. After reading copies of The Catholic Worker that I had found in my parish library, and then reading Dorothy’s autobiography, The Long Loneliness, I decided to visit the community she had founded. I was based not so far away, in Washington, DC.

Arriving in Manhattan for that first visit, I made my way to Saint Joseph’s House — then in a loft on Spring Street, on the north edge of Little Italy in the Lower East Side of New York City. Discovering that it was moving day, I joined in helping carry boxes from an upstairs loft to a three-storey brick building at 175 Chrystie Street, a few blocks to the east. Jack Baker, one of the other people assisting with the move that day, invited me to stay in his apartment in the same neighborhood. A few days later I visited the community’s rural outpost on Staten Island, the Peter Maurin Farm. Crossing Upper New York Harbor by ferry, I made my way to an old farmhouse on a rural road just north of Pleasant Plains near the island’s southern tip. In its large, faded dining room, I found half-a-dozen people, Dorothy among them, gathered around a pot of tea at one end of the dining room table.

Read the rest of this article »

An Open Letter to the Occupy Movement from Starhawk and the Alliance of Community Trainers.

Nonviolent direct action clearly dramatizes the difference between the corrupt values of the system and the values we stand for. Their institutions silence dissent, while we value every voice. They employ violence to maintain their system, while we counter it with the sheer courage of our presence.

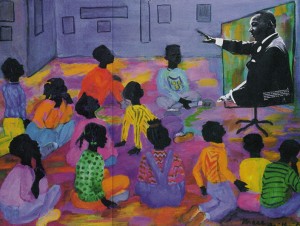

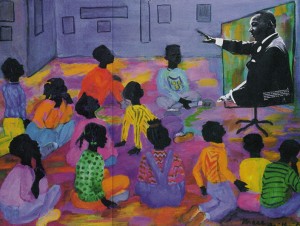

Grace BRAITHWAITE. Martin Luther King, Jr.:

Learning at the Feet of the Master; oil on canvas;

courtesy Syracuse Cultural Workers Peace Calendar 2012.

The Occupy movement has had enormous success in the short time since September when activists took over a square near Wall Street. It has attracted hundreds of thousands of active participants, spawned occupations in cities all over North America, changed the national dialogue and garnered enormous public support. It has even, on occasion, gotten good press!

Now we are wrestling with the question that arises again and again in movements for social justice: how to struggle. Do we embrace nonviolence, or a diversity of tactics? If we are a nonviolent movement, how do we define nonviolence? Is breaking a window violent?

Read the rest of this article »

by Rosemary Morrow

“It is, perhaps, the greatest failure of collective leadership since the first world war. The Earth’s living systems are collapsing, and the leaders of some of the most powerful nations – the US, the UK, Germany, Russia – could not even be bothered to turn up and discuss it. Those who did attend the Earth summit last week solemnly agreed to keep stoking the destructive fires: sixteen times in their text they pledged to pursue “sustained growth”, the primary cause of the biosphere’s losses.”

This was the opening paragraph by George Monbiot in the Guardian (25 June 2012) at the end of the Earth Summit convened to rescue all life from global climate change and other degradation. Those of us who follow the science feel dismayed.

Yet it has left us with only one path, that of ahimsa, nonviolence and almost certainly civil disobedience. As with M. Gandhi’s struggle for independence, we must be prepared to break the laws. We must disregard those who have no care for Nature and Life as we know it. We must abandon any sense that we will be saved by others. We must act as Earth’s residents, to restore Earth’s living systems, impelled by kindness, compassion and conscience for Nature.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vandana Shiva

Gandhi on the Salt March, 1930.

In Hind Swaraj, Gandhi exhorts using ‘soul force’ as a means to seek ‘right livelihood’ – which is what real freedom is all about. Gandhi’s Hind Swaraj has, for me, been the best teaching on real freedom. It teaches the gospel of love in place of hate. It replaces violence with self-sacrifice. It puts ‘soul force’ against brute force. For Gandhi, slavery and violence were not just a consequence of imperialism: a deeper slavery and violence were intrinsic to industrialism, which Gandhi called “modern civilisation”.He identified modern civilisation as the real cause of loss of freedom. “Civilisation seeks to increase bodily comforts and it fails miserably even in doing so… This civilisation is such that one has only to be patient and it will be self-destroyed.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Miki Kashtan

One of the most frequent questions I hear when I speak about Nonviolent Communication is “Why Nonviolent?” People often hear the word nonviolent as a combination of two words, as a negation of violence. Since they don’t think of themselves as “violent,” the concept of “non-violence” doesn’t make intuitive sense, and appears foreign to them.

For some time, I felt similarly. I was happier when I heard people talk about Compassionate Communication instead of Nonviolent Communication (NVC) because it felt more positive. After all, the practice of NVC itself is about focusing on what we want and where we are going instead of looking at what’s not working. So why would the name not reflect this focus?

Like others, I was unaware of the long-standing tradition of nonviolence to which the practice of Nonviolent Communication traces its origins. Then I learned more about Gandhi’s work and the Civil Rights movement. That is when I fell in love with the name Marshall Rosenberg gave to this practice. That love has deepened over the years. Now I want to bring out the continuity so as to situate NVC within the tradition of nonviolence. I do this by exploring seven core principles of Gandhian nonviolence that are also reflected in the practice of NVC.

Read the rest of this article »