by Terry Messman

The White Train transported nuclear weapons to military bases across the nation; photo by Chris Guenzler, courtesy thestreetspirit.org

Street Spirit: The White Train campaign mobilized people in hundreds of far-flung communities to stand in nonviolent resistance along the tracks where nuclear weapons were transported. How did the White Train campaign get started?

Jim Douglass: Well, the White Train campaign began as the Tracks campaign at a time when we didn’t yet know there was a White Train. Shelley and I had been looking at a house for years next to the Trident base as a location that was analogous to the Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action, which was itself a piece of land 3.8 acres in size alongside the Trident base that we had bought as a community.

Read the rest of this article »

by Max Cooper

Logo courtesy practicingparrhesia.tumblr.com

We noted in two previous essays comparing Gandhi and Foucault that our study was apparently the first specifically to compare the lives and philosophies of Mahatma Gandhi and Michel Foucault, and the first to suggest Gandhi as Foucault’s wished-for modern exemplar of the Hellenistic ideals of epimeleia heautou and parrhesia. Considering the mass of scholarship relating to the work of Foucault, and indeed the vast and meticulous output of the academic enterprise generally, it seems curious that we should be the first to draw these connections. This afterword will briefly inquire as to why this should be the case. Suggesting that possible concerns with our claims (Gandhi as exemplifying epimeleia and parrhesia) are generally unfounded, we will propose that this small lacuna rather reflects a greater and more troubling chasm between Eastern and Western philosophy in contemporary academia. We hope, therefore, that further projects may span the gap between two ancient traditions of human wisdom.

Read the rest of this article »

by Joan V. Bondurant

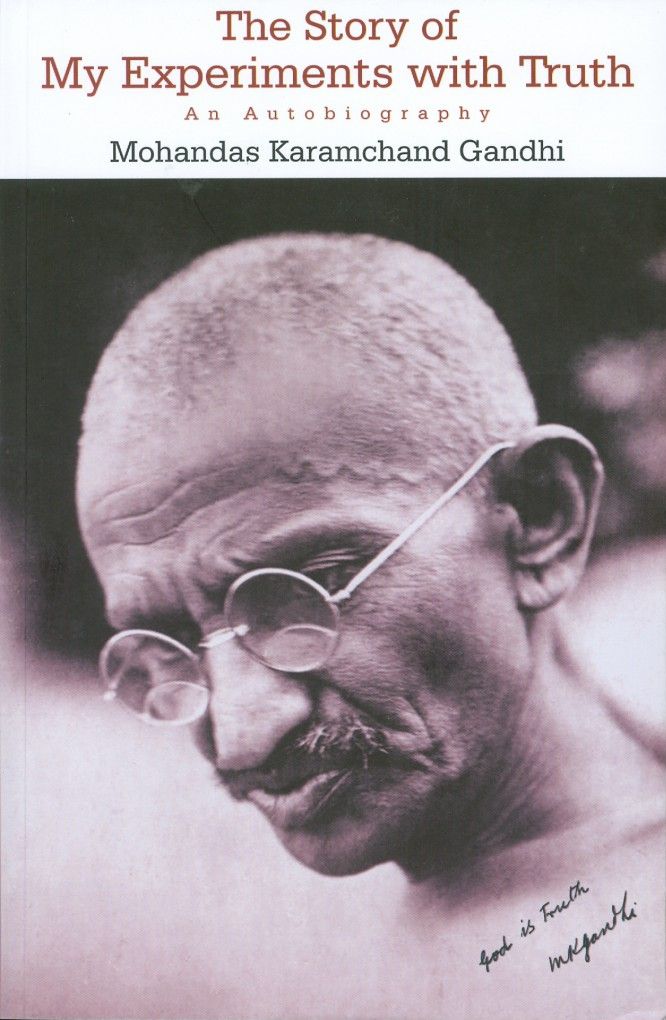

Jacket art courtesy Princeton University Press

Every leader who seeks to win a battle without violence and who presumes to precipitate a war against conventional attitudes and arrangements, however prejudiced they may be, would do well to probe the subtleties distinguishing satyagraha from other forms of action also claiming to be nonviolent. There are essential elements in Gandhian satyagraha which do not readily meet the eye. The readiness with which Gandhi’s name is invoked and the self-satisfaction with which leaders of movements throughout the world make reference to Gandhian methods are not always backed by an understanding of either the subtleties or the basic principles of satyagraha. It is important to pose a question and to state a challenge to those who believe that they know how a Gandhian movement is to be conducted. For nonviolence alone is weak, non-cooperation in itself could lead to defeat, and civil disobedience without creative action may end in alienation. How, then, does satyagraha differ from other approaches? This question can be explored by contrasting satyagraha with concepts of passive resistance defined by the Indian word duragraha.

Duragraha means prejudgment. Perhaps better than any other single word, it connotes the attributes of passive resistance. Duragraha may be said to be stubborn resistance in a cause, or willfulness. The distinctions between duragraha and satyagraha, when these words are used to designate concepts of direct social action, are to be found in each of the major facets of such action. (1) Let us examine: (a) the character of the objective for which the action is undertaken; (b) the process through which the objective is expected to be secured, and (c) the styles which characterize the respective approaches. Satyagraha and duragraha are compared below in each of these three aspects by considering their relative treatment of first, pressure and persuasion, and second, guilt and responsibility. Finally, we shall have a look at the meaning and limitations of symbolic violence.

Read the rest of this article »

by Max Cooper

Editor’s Preface: This essay is the second of three by Max Cooper comparing similarities between Gandhi and Michel Foucault. The first we posted 1 June and can be accessed via his Author’s Page, by clicking on his byline. Part Three will follow in a few days. Please also consult the Editor’s Note at the end for biographical information. JG

Cover art courtesy Semiotext(e)

We will here explore Foucault’s interests in the final years of his life in two particular ethico-spiritual practices native to ancient Greek and Hellenistic philosophy: epimeliea heautou, the care of the self, and parrhesia, fearless truth-telling. Foucault saw such disciplines as important foundations for an ethical life; lamenting that such foundations could not be found in the modern age, he wished to draw attention to these practices in the hope that they might somehow be revived. We will argue here that Foucault need not have looked back over two thousand years to the ancient Greeks and Hellenes for examples of these practices, but could have found virtually identical practices in the life of Gandhi in his own century. We will suggest ultimately that Gandhi represented precisely the modern practitioner of epimeleia heautou and parrhesia that Foucault was looking for.

Examining certain classicist scholars’ criticisms of Foucault on his interpretation of these practices, we will entertain the striking possibility that Gandhi may have come closer to exemplifying these ancient practices and beliefs than Foucault did to explaining them. Next, we will examine Foucault’s intriguing distinction between ancient and modern philosophy as pertains to the care of the self: most ancient philosophers, Foucault suggested, viewed the attainment of knowledge as possible only after one had performed painstaking preparatory work on oneself; this often took the form of particular “spiritual practices.” Foucault felt that modern philosophy since Descartes had lost this emphasis on preparation for knowledge, to its own great detriment. We suggest that Gandhi, through his rigorous programme of self-purification performed with the goal of realizing Absolute Truth, embodies almost precisely the characteristics of epimeleia heautou that Foucault drew attention to in his classical sources: again, Foucault could have taken heart in Gandhi’s example.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

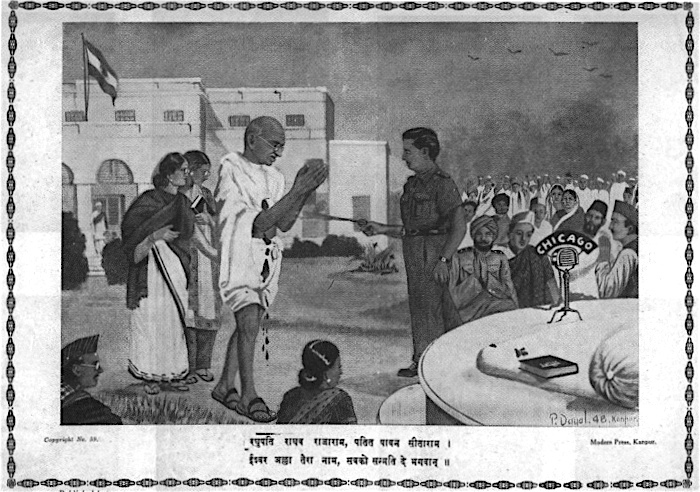

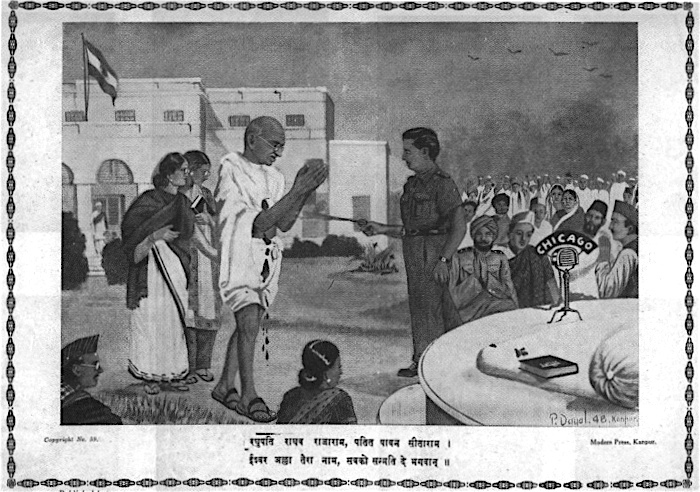

Popular Hindi press representation of Gandhi’s assassination; courtesy Vinay Lal collection

As India marked the 60th anniversary [2008] of Gandhi’s death, the tired old question of Gandhi’s “relevance” was rehearsed in the press. Once past the common rituals, we heard that the spiral of violence in which much of the world seems to be caught demonstrates Gandhi’s continuing relevance. Barack Obama’s ascendancy to the Presidency of the United States furnishes one of the latest iterations of the globalizing tendencies of the Gandhian narrative. Unlike his predecessor, who flaunted his disdain for reading, Obama is said to have a passion for books; and Gandhi’s autobiography has been described as occupying a prominent place in the reading that has shaped the country’s first African American President. Obama gravitated from “Change We Can Believe In” to “Change We Need”, but in either case the slogan is reminiscent of the saying to which Gandhi’s name is firmly, indeed irrevocably, attached: “We Must Become the Change We Want To See In the World.” Obama’s Nobel Prize Lecture twice invoked Gandhi, if only to rehearse some familiar clichés – among them, the argument, which has seldom been scrutinized, so infallible it seems, that Gandhian nonviolence only succeeded because his foes were the gentlemanly English rather than Nazi brutes or Stalinist thugs.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

Indian folk art representation of Gandhi’s assassination; courtesy Vinay Lal collection

Uniquely among the major public figures of the modern world, Mohandas Gandhi attracted an extraordinarily wide and diverse following and, perhaps oddly for someone who is customarily thought of in terms of veneration, an equally if not more diverse array of often relentlessly hostile critics. (1) The first part of this story is better known than the latter part of the narrative around which this paper is framed, (2) though much remains to be understood about the manner in which Gandhi, notwithstanding his rather strident views on modernity, industrial civilisation, materialism, sexual relations, indeed on everything that is ordinarily encompassed under the rubric of social and political life, drew to himself people from very different walks of life.

Among his most intimate disciples, who, it is no exaggeration to say, surrendered their life to the Mahatma, one thinks of the daughter of an English admiral, raised on the music of Beethoven in the lap of luxury and immense privilege; a Tamil Christian, trained as an accountant and economist, who was among the first Indians to earn a degree in business administration; a Gujarati villager, son of a schoolteacher, who was embraced by Gandhi when they first met in 1917 as something like a long-lost son; and an Anglican clergyman, arriving in India from Britain on what was destined to become a one-way ticket, who came to the realization that Gandhi was a better Christian than many who call themselves Christians. (3)

Read the rest of this article »

by Max Cooper

Poster art, courtesy indorigins.com

It may seem surprising that no significant study has as yet compared the lives, works, and ideas of Mahatma Gandhi and Michel Foucault. (1) Foucault (1926–1984), a French political and social theorist, and Gandhi (1869–1948), the saintly Indian political leader, initially appear to have very little in common, and indeed strike us as intellectual opposites. Gandhi was a deeply religious man who committed at least an hour each day to prayer and meditation; Foucault was a committed atheist who resented his bourgeois Catholic upbringing and blamed religion for much of the malaise afflicting modern man. Gandhi believed that human society and relationships could be transformed through individual hard work, selfless kindness, and love; Foucault was concerned to draw attention to hidden motivations of power in all social relations, and emphasized the often powerless positions of individuals vis-à-vis larger institutional structures. Gandhi fasted regularly, never took food after sunset, and upheld a vow of strict brahmacharya (celibacy) for the last 38 years of his marriage; Foucault maintained a fascination with intense sensory experiences, ever seeking stronger sensations through drugs and sex, and explored his interest in sexual pleasure in his final and definitive works, the three volume History of Sexuality. The reader could be forgiven for thinking that two more different men could hardly be found.

Read the rest of this article »

by M. P. Mathai

Tree hugging photograph; courtesy spiritualecology.org

The ecological crisis we confront today has been analysed from various angles, and scientific data on the state of our environment are readily available. Humanity has come out of its foolish self-complacency and has awakened to the realisation that over-exploitation of nature has led to a very severe degradation and devastation of our environment. Scholars, through joint studies and research projects, have brought out the direct connection between consumption and environmental degradation. For example, professor of planning and development, Inge Ropke, has raised pertinent questions in his paper, “The Dynamics of the Willingness to Consume”: Why are productivity increases largely transformed into income increases instead of more leisure? Why is such a large part of these income increases used for consumption of goods and services with a relatively high materials-intensity instead of less material-intensive alternatives?

Read the rest of this article »

by Prof. Giovanni Pioli

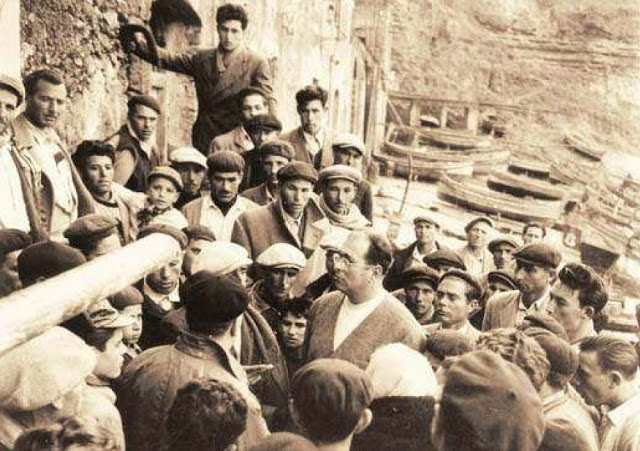

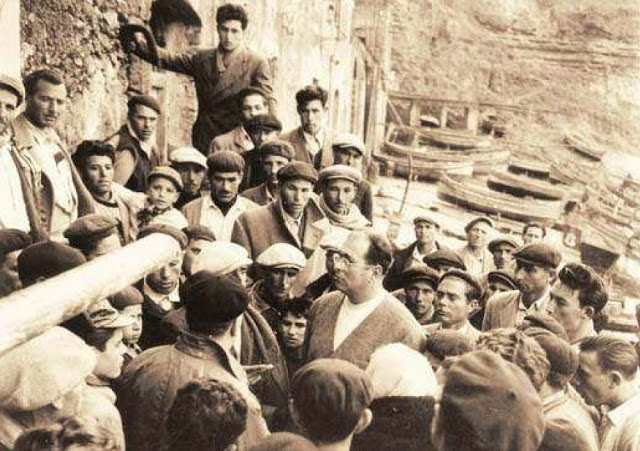

Dolci organzing the fishermen of Trappeto, 1952; courtesy en.wikipedia.org

Editor’s Preface: This article continues our series of historically important articles from the War Resisters’ International archive, our goal to trace the influence of Gandhian nonviolence on the early pacifist movements. This is from The War Resister, issue 71, Second Quarter 1956. We have previously published articles by or about Dolci, one of the great exponents of Gandhi’s constructive program. These may be accessed via our search box. Please consult the notes at the end for further information. JG

Pamphlets, bulletins and books have now been written by Danilo Dolci and the valiant men and women who join him for a time to share his experience, his poverty, his distress and his hard labour for the uplift of those submerged, demoralised ‘criminal’ masses who struggle — even beyond legal limits — for the bare necessities of life. Italian social workers, pacifists, and humanitarians respect this literature, dealing with conditions in Trappeto and Partinico, situated in the Province of Palermo, Sicily — infamous as a centre of Sicilian banditry and the mafia.

Read the rest of this article »

by Dr. Susan S. Bean

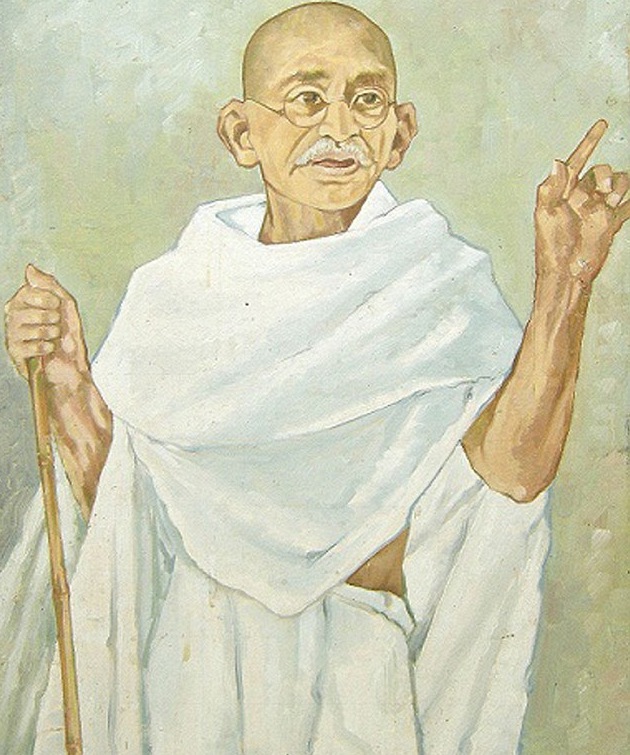

Painting of Gandhi, c. 1945, by J. L. Bhandari; courtesy dailymail.co.uk

Prologue: The story of khadi (homespun) and its creator Mohandas Gandhi is well known in India and around the world. In his political campaign for Indian self-determination (swaraj), Gandhi famously promoted the practices of making thread through spinning by hand, and wearing simple khadi garments – not only as key symbols of national identity, but also as a central statement of resistance to the colonial regime. As writer, producer and director, Gandhi instigated a national drama centred on the roles of spinner and khadi-wearer. Made from hand-spun yarn, his khadi would emerge from India’s handlooms not just to costume the nation but also to change the essential character of its people, altering colonial subjects into ‘citizens’. Seen as theatre, the narrative of khadi reveals how Gandhi transformed this cloth into much more than a mere textile, and how khadi exerted transformative and long lasting effects in India’s national movement. The drama of khadi illuminates the potency and tenacity inherent in this humble homespun cloth; already having proved itself within the framework of the freedom struggle, the story of khadi still resonates more than sixty years after India gained Independence. (1)

Read the rest of this article »