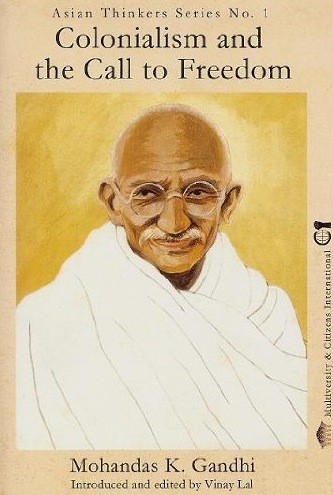

Author Archive: Vinay Lal

VINAY LAL is Professor of History and Asian American Studies at UCLA. He writes widely on the history and culture of colonial and modern India, popular and public culture in India (especially cinema), the politics of world history, the Indian diaspora, contemporary American politics, and the life and thought of Mohandas Gandhi. He is the author or editor of over fifteen books.

His exceptional blog site gives a full biography, and list of his publications, and is regularly updated with a wealth of articles on India.

by Vinay Lal

“Caring for Our Common Home”; artwork courtesy parochiesintmaarten.nl

The thinking person, as Walter Benjamin had occasion to remark, appears to experience crisis at every juncture of her or his life. How can this not be so if one were to experience the pain of someone else as one’s own? How can this not be so when, amidst growing stockpiles of food in many countries, millions continue to suffer from malnutrition, and the lengthening shadows of poverty give lie to the pious promises and pompous proclamations by the world’s leaders over the last several decades that humanity is determined to achieve victory in its quest to eradicate poverty? With war, violence, disease, and the myriad manifestations of racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination which man’s ingenuity has wrought all around us, how might a person not be experiencing crisis? One foundation after another—whether it be named after Bill and Melinda Gates, the Clintons, Ford, Rockefeller, or other tycoons—has claimed to have helped “millions” of people around the world, but the crises appear to be multiplying.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

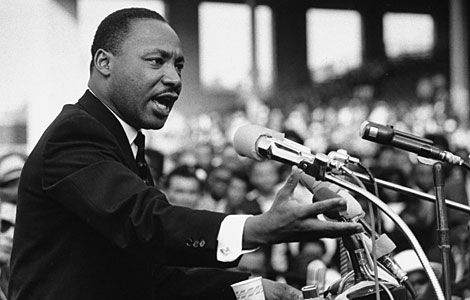

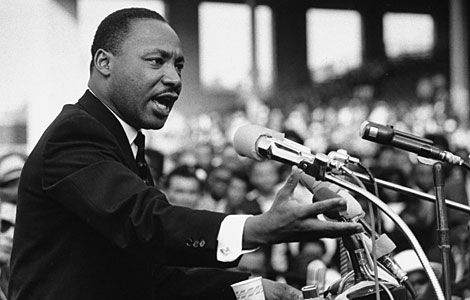

Martin Luther King, at Southern Christian Leadership Conference; courtesy vinaylal.wordpress.com

Whatever the difficulties that Martin Luther King encountered in his relentless struggle to secure equality and justice for black people, and whatever the temptations that were thrown in his way that might have led him to abandon the path that he had chosen to lead his people to the “promised land”, it is remarkable that King’s principled commitment to nonviolence never wavered through the long years of the struggle. “From the very beginning”, he told an audience in 1957, “there was a philosophy undergirding the Montgomery boycott, the philosophy of nonviolent resistance.” His own “pilgrimage to nonviolence” commenced, King wrote in Stride Toward Freedom (1958), with the realization that “the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

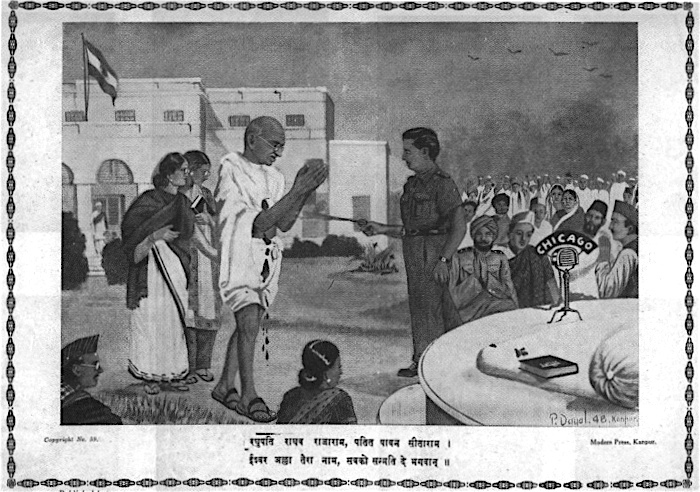

Popular Hindi press representation of Gandhi’s assassination; courtesy Vinay Lal collection

As India marked the 60th anniversary [2008] of Gandhi’s death, the tired old question of Gandhi’s “relevance” was rehearsed in the press. Once past the common rituals, we heard that the spiral of violence in which much of the world seems to be caught demonstrates Gandhi’s continuing relevance. Barack Obama’s ascendancy to the Presidency of the United States furnishes one of the latest iterations of the globalizing tendencies of the Gandhian narrative. Unlike his predecessor, who flaunted his disdain for reading, Obama is said to have a passion for books; and Gandhi’s autobiography has been described as occupying a prominent place in the reading that has shaped the country’s first African American President. Obama gravitated from “Change We Can Believe In” to “Change We Need”, but in either case the slogan is reminiscent of the saying to which Gandhi’s name is firmly, indeed irrevocably, attached: “We Must Become the Change We Want To See In the World.” Obama’s Nobel Prize Lecture twice invoked Gandhi, if only to rehearse some familiar clichés – among them, the argument, which has seldom been scrutinized, so infallible it seems, that Gandhian nonviolence only succeeded because his foes were the gentlemanly English rather than Nazi brutes or Stalinist thugs.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

Indian folk art representation of Gandhi’s assassination; courtesy Vinay Lal collection

Uniquely among the major public figures of the modern world, Mohandas Gandhi attracted an extraordinarily wide and diverse following and, perhaps oddly for someone who is customarily thought of in terms of veneration, an equally if not more diverse array of often relentlessly hostile critics. (1) The first part of this story is better known than the latter part of the narrative around which this paper is framed, (2) though much remains to be understood about the manner in which Gandhi, notwithstanding his rather strident views on modernity, industrial civilisation, materialism, sexual relations, indeed on everything that is ordinarily encompassed under the rubric of social and political life, drew to himself people from very different walks of life.

Among his most intimate disciples, who, it is no exaggeration to say, surrendered their life to the Mahatma, one thinks of the daughter of an English admiral, raised on the music of Beethoven in the lap of luxury and immense privilege; a Tamil Christian, trained as an accountant and economist, who was among the first Indians to earn a degree in business administration; a Gujarati villager, son of a schoolteacher, who was embraced by Gandhi when they first met in 1917 as something like a long-lost son; and an Anglican clergyman, arriving in India from Britain on what was destined to become a one-way ticket, who came to the realization that Gandhi was a better Christian than many who call themselves Christians. (3)

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

Illustration courtesy mayapur.com

More so than any other major political figure of modern times, Mohandas Gandhi was a man of religion – though perhaps not in the most ordinary sense of the term. No political figure of the last few hundred years brought religion, or more properly the religious sensibility, into the public domain as much as Gandhi. He concluded his autobiography, first published in 1927, with the observation that those who sought to disassociate politics and religion understood the meaning of neither politics nor religion. Indeed, the most pointed inference we can draw from Gandhi’s life is the following: the only way to be religious at this juncture of human history is to engage in the political life, not politics in the debased sense of party affiliations, or the politics that one associates with being conservative or liberal, but politics in the sense of political awareness. After Gandhi, we must clearly understand, as did Arnold Toynbee and George Orwell, that the saint’s religiosity can only be tested in the slums of life.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

Cover art courtesy vedicbooks.net

In a lecture given in 1993, the Indian historian Ramachandra Guha proposed to inquire whether Gandhi could be considered an “early environmentalist”. (1) Gandhi’s voluminous writings are littered with remarks on man’s exploitation of nature, and his views about the excesses of materialism and industrial civilization, of which he was a vociferous critic, can reasonably be inferred from his famous pronouncement that the earth has enough to satisfy everyone’s needs but not everyone’s greed. Still, when ‘nature’ is viewed in the conventional sense, Gandhi was rather remarkably reticent on the relationship of humans to their external environment. His name is associated with innumerable political movements of defiance against British rule as well as social reform campaigns, but it is striking that he never explicitly initiated an environmental movement, nor does the word ‘ecology’ appear in his writings. Again, though commercial forestry had commenced well before Gandhi’s time, and the depletion of Indian forests would persistently provoke peasant resistance, Gandhi himself was never associated with forest satyagrahas, however much peasants and rebels invoked his name.

Guha also observes that, “the wilderness had no attraction for Gandhi.” (2) His writings are singularly devoid of any celebration of untamed nature or rejoicing at the chance sighting of a wondrous waterfall or an imposing Himalayan peak; and indeed his autobiography remains utterly silent on his experience of the ocean, over which he took an unusually long number of journeys for an Indian of his time. In Gandhi’s innumerable trips to Indian villages and the countryside — and seldom had any Indian acquired so intimate a familiarity with the smell of the earth and the feel of the soil across a vast land — he almost never had occasion to take note of the trees, vegetation, landscape, or animals. He was by no means indifferent to animals, but he could only comprehend them in a domestic capacity. Students of Gandhi certainly are aware not only of the goat that he kept by his side and of his passionate commitment to cow-protection, but of his profound attachment to what he often described as ‘dumb creation’, indeed to all living forms.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

Cover art courtesy Vinay Lal

The enterprise of making a nation is fraught with violence. People have to be not merely cajoled but browbeaten into submission to become proper subjects of a proper nation-state. Overt violence may not always play the primary role in producing the homogenous subject, but social phenomena such as schooling cannot be viewed merely as innocuous enterprises designed to ‘educate’ subjects of the state. One of the most widely cited works to have put forward this argument with elegance and scholarly rigor is Eugen Weber’s Peasants into Frenchmen, where one learns, with much surprise, that even in the Third Republic, “French was a foreign language for half the citizens.” The making of France entailed not only the modernization of the rural countryside but creating, often with violence, proper subjects of a proper nation-state. The making of the United States offers another narrative of the role of violence in the production of the nation-state, with the extermination of Native Americans long before and much after the ‘Revolutionary War’ constituting the most vital link in the long chain of violence that marked the emergence of the United States.

Postcolonial thought, attentive as always to the politics of nation-making and nationalism’s complicity with colonialism, bestowed considerable attention on the various phenomena that can be accumulated under the rubric of violence; however, it had almost no time to spare for a pragmatic, ethical, or even philosophical consideration of nonviolence. The violence of the nation-state may have always been present to the mind of postcolonial theorists, but generally this was reduced to the violence of the colonizer. One thinks, of course, of Fanon, Cesaire, Memmi, and many others in this respect. In those works that have underscored the complicity of nationalist and imperialist thought, a principal motif in the work (say) of Ranajit Guha, the violence of indigenous elites also came under critical scrutiny. (See, for example, Guha’s Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India, Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1999) It is characteristic of most social thought in the West that it has been riveted on violence – here, postcolonial thought barely diverged from orthodox social science, mainstream social thought, or the general drift of humanist thinking. Nonviolence is barely present in intellectual discussions. We see here history’s continuing enchantment with ‘events’; nonviolence creates little or no noise, it merely is, it only fills the space in the background.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

Book cover art courtesy navajivantrust.org

A celibate for the greater part of his life, Mohandas Gandhi continues to attract nearly unrivalled attention – often for the sex that did not take place. Even his friends and admirers, who revered him for bringing ethics to the political life, or for never demanding of others what he did not first demand of himself, were quite certain that Gandhi was unable to comprehend that a woman and a man might enjoy a perfectly healthy sexual relationship with each other. Nehru, seldom critical of the personal life of his political mentor, was convinced that Gandhi harboured an “unnatural” suspicion of the sexual life; and he deplored, as did many others, Gandhi’s strongly held view that sexual intercourse, other than for purposes of procreation, had no place in civilised life – not even among married couples. The Marxists have long subscribed to the view that Gandhi was a “romantic”, a hopeless idealist and even hypocrite; to this a chorus of voices added the thought that Gandhi was an insufferable “puritan”.

Gandhi’s discomfort with the sexual life, according to one widely accepted strand of thought, commenced when his father passed away shortly after his marriage to Kasturba. Though the young Gandhi liked to nurse his ailing father, one evening he was unable to contain his urge to share a night of ribaldry with his young wife. He had just withdrawn to the bedroom when a knock on the door announced that his father had passed away. Gandhi was, it has been argued, never able to forgive himself his transgression, and became determined to master his sexual drive. A more complex narrative links his renunciation of sex to his firm conviction, first developed during the heat of a campaign of nonviolent resistance to oppression in South Africa, that it compromised his ability to be a perfect satyagrahi. Many commentators have pointed to his failure to consult with Kasturba before he took a vow of celibacy at the age of 37 as a sign of his cruelty and tendency to be self-serving.

Read the rest of this article »