Guest Editorial: Martin Luther King and the Commitment to Nonviolence

by Vinay Lal

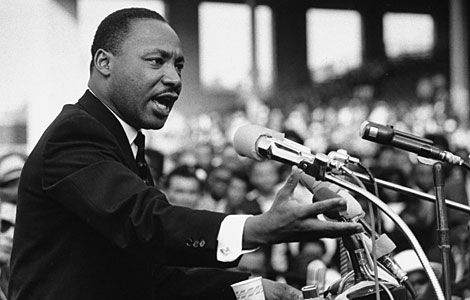

Martin Luther King, at Southern Christian Leadership Conference; courtesy vinaylal.wordpress.com

Whatever the difficulties that Martin Luther King encountered in his relentless struggle to secure equality and justice for black people, and whatever the temptations that were thrown in his way that might have led him to abandon the path that he had chosen to lead his people to the “promised land”, it is remarkable that King’s principled commitment to nonviolence never wavered through the long years of the struggle. “From the very beginning”, he told an audience in 1957, “there was a philosophy undergirding the Montgomery boycott, the philosophy of nonviolent resistance.” His own “pilgrimage to nonviolence” commenced, King wrote in Stride Toward Freedom (1958), with the realization that “the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom.”

Over the years, even as King encountered determined resistance to his advocacy of nonviolent resistance, both among white racists, and black activists who taunted him for cuddling up to the white man, his faith in the efficacy of nonviolence intensified. In his last years, he increasingly embraced the idea that nonviolence would be deployed not only against oppression by the state, and to arouse the moral conscience of his white opponents, but also to secure greater equality and social justice for the working class in American society. It was King’s support of the sanitation workers’ strike that brought him to Memphis where, on the eve before his assassination, he delivered the “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech with the exhortation to his listeners to “give ourselves to this struggle until the end. Nothing would be more tragic than to stop at this point in Memphis. We’ve got to see it through.”

What remains of the grand idea of nonviolence? If the twentieth century was perhaps the most violence-laden century in recorded history, a time of “total war”, it is befitting that the most creative responses to the brutalization of the human spirit should have also come in the twentieth century, in the shape of nonviolent movements led by Gandhi, American civil rights activists, Cesar Chavez, Chief Albert Luthuli in South Africa, and others. But it cannot be said that the need for nonviolence has diminished, considering that large parts of the world appear to be enflamed by violence and turmoil. Entire towns in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen have been reduced to rubble, and there is every possibility that all three countries will eventually unravel and fragment. Over 4.6 million Syrians are officially registered as refugees, but there are many other countries outside the Middle East that have been torn apart by violence, among them Afghanistan, Somalia, Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The United States, far removed as it is from falling bombs, drone attacks, or the refugee crisis, has nonetheless seen its share of discussions about escalating violence. Though gun shootings are now commonplace, the soul-searching has produced not a new wave of activists committed to nonviolence but rather a substantial upsurge in sales of firearms and ammunition. What is striking about American political discourse is the ease with which so many people, not just members of the National Rifle Association (NRA), have accepted the view that they can best protect themselves and their families from random gun shootings by arming themselves to the teeth. The other central issue around which much political mobilization has taken place, namely police violence against black people, has similarly not spurred activists to the creative use of nonviolent modes of resistance.

Some people will point to the Black Lives Matter movement to suggest that nonviolent resistance has in fact found a new lease of life. It is not to be doubted that BLM has mobilized social media, staged marches and demonstrations, and highlighted not only police brutality but even more systemic forms of injustice and discrimination that justify the characterization of the United States as an incarceration state, especially with respect to black people. But nonviolence, in the hands of its most famous practitioners and theorists, never meant merely the abstention from violence, nor is it encompassed solely by the embrace of tactics designed as ad-hoc gestures to meet the exigencies of a situation. Intense nonviolence training workshops were an intrinsic and critical part of the movements that shaped the struggle for civil rights in the US.

One does not see, within the Black Lives Matter movement, or in the writings and public lives of contemporary African American intellectuals, anything even remotely resembling the kind of extraordinary leadership that characterized the American civil rights movement. It is not just nostalgia that leads one to ask where are to be found the likes of King, Bayard Rustin, James Farmer, or A. Philip Randolph. The Rev. James Lawson, now 87 years old, still soldiers on and remains the stellar example of a life dedicated to the idea of nonviolence. For him, as for King and others, nonviolence was never simply an afterthought, or something that was to be resorted to when all other options had failed. Nonviolence was stitched into the fabric of their being. What has become all too common now is to try out nonviolence and shelve it if it does not offer instant results or gratification, and then proclaim it a “failure”; on the other hand, it must be human ingenuity, and an enchantment with violence, which enables people to continue to resort to it even as its horrific toll mounts. It is well to remember at this juncture, as Gandhi and King insistently repeated, that when nonviolence seems not to have succeeded, it is not because nonviolence has failed us but rather because we have failed nonviolence.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Vinay Lal is Professor of History and Asian American Studies at UCLA. He writes widely on the history and culture of colonial and modern India, popular and public culture in India (especially cinema), historiography, the politics of world history, the Indian diaspora, global politics, contemporary American politics, and the life and thought of Mohandas Gandhi. He is the author or editor of over fifteen books. His exceptional blog site gives a full biography, and list of his publications, and is regularly updated with a wealth of articles on India and Gandhi. Lal also has a YouTube channel featuring an excellent lecture series on Gandhi’s moral and political thought, the best such teaching aide we’ve seen on the web.