Danilo Dolci’s Nonviolent Revolution in Sicily

by Prof. Giovanni Pioli

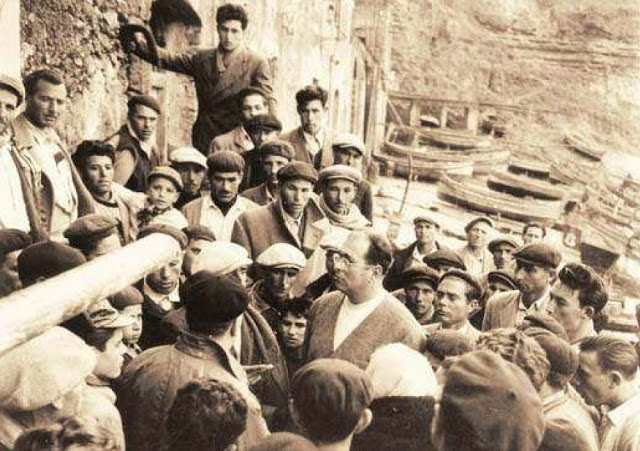

Dolci organzing the fishermen of Trappeto, 1952; courtesy en.wikipedia.org

Editor’s Preface: This article continues our series of historically important articles from the War Resisters’ International archive, our goal to trace the influence of Gandhian nonviolence on the early pacifist movements. This is from The War Resister, issue 71, Second Quarter 1956. We have previously published articles by or about Dolci, one of the great exponents of Gandhi’s constructive program. These may be accessed via our search box. Please consult the notes at the end for further information. JG

Pamphlets, bulletins and books have now been written by Danilo Dolci and the valiant men and women who join him for a time to share his experience, his poverty, his distress and his hard labour for the uplift of those submerged, demoralised ‘criminal’ masses who struggle — even beyond legal limits — for the bare necessities of life. Italian social workers, pacifists, and humanitarians respect this literature, dealing with conditions in Trappeto and Partinico, situated in the Province of Palermo, Sicily — infamous as a centre of Sicilian banditry and the mafia.

People are Starving

As Dolci states, ‘In this district where fifty percent of the 50,000 people are starving and too many escape death only by trespassing on the rights of others, someone this moment is actually dying of starvation because we have lent no helping hand. To shoot these people is no remedy. On the contrary it is a display of banditry on a wider scale . . . It is no work of justice to march against a people in dire need. People are blind with exasperation . . . Come and watch the quarrels between members of the same family when clothes are distributed to those most in need and food to those whose hunger is so furious they literally bite the hands stretched forth to appease that hunger. Feel the fury of people lacking the education to control themselves, their minds deadened by the morally sick climate. Come and hear the plans which little children of murdered and imprisoned parents, confide to one another before falling into troubled sleep. What horrible vengeance their childish souls plot unless we teach them to send “kisses” even to those who have imprisoned or killed their fathers, or may do so!’

To persons of goodwill who offer to help him, Danilo Dolci warns, ‘No one should dream of coming here in his or her best clothes or of finding lodgings or one’s accustomed food and comfort. You cannot dodge, in your contacts with the people, the dirt and stink and repelling spectacles both material and moral. To live even in primitive comfort in this Kingdom of Misery would seem, by comparison, an insult to the people you wish to serve.’

These quotations show something of the conditions in which Danilo Dolci and his co-workers are conducting their great experiment. They seek to raise the people’s morale, to inspire them with self-confidence and a sense of solidarity and to help them to help themselves without resorting to violence or revenge.

Dolci’s Previous Work

But let us go back a bit, nearer the beginning. A short account should be given of this young man, born in 1924 and now 35 years old, who abandoned his study of architecture on the eve of his doctorate. He felt inwardly compelled to follow the Roman Catholic priest Don Zeno Santini, founder of the charitable organization Nomadelfia, whose mission was to care for orphaned and impoverished children, by creating a village atmosphere, or as Dolci was himself to describe it, ‘a town of brethren under the law of love’.

After years of devoted work in Nomadelfia, in February of 1952 Dolci returned to the poor fishing village of Trappeto, on the west coast of Sicily not far from Palermo, where he had spent some of his childhood. When he arrived, he had only 30 lire to his name (at that time just a few pounds) and the clothes he was wearing, having lived a life of voluntary poverty at Nomadelfia. He would work and live with the poor, get to know and to understand them, and perhaps solve the puzzle of their endemic banditry.

He chose to live in the worst slum of Trappeto, Vallone, a neighbourhood made up largely of impoverished fishermen and farmers. Later he conducted his first house-to-house surveys and interviews here, the basis of his first books. His house, as were most, was a single room, which must meet every need for an average of six persons. Generally there was no access to running water and only a few broken pieces of furniture, including a rag-covered bed or two. Even for serious illnesses, there was no available treatment. On rare occasions ludicrously small welfare payments were granted to the unemployed, but even more rarely were they paid on any regular basis. Nearly all the adults were illiterate. A later study of 350 Trappeto males, all of whom had served prison time, showed that each had spent, on the average, one year in school and over nine years in prison!

Dramatic Decision

Dolci was at a loss as to how one might cope with this awful situation, and his sense of helplessness lay unbearably heavy upon him. One day, in the autumn of 1952, the year of his arrival, a baby died in his arms because its mother had no milk nor money to buy any milk, and Dolci made his decision: he would lie in the same bed that saw the baby’s death, and fast until the State allocated millions of lire to alleviate the poverty. Word of his decision spread like wildfire. Newspapers reported the case with screaming banners. After seven days of fasting, the President of the Sicilian Region sent a cheque for one million lire (about 5000 pounds), an enormous amount for those who lived on nothing. Dolci decided to spare his own life and renew the struggle.

Accomplishments

With this initial contribution, and money that began to pour in from all over Italy, Dolci purchased land and built a house for his new wife and staunch collaborator — the widow of a fisherman with five orphaned boys. Next, he built an asylum for destitute children, on the model of Nomadelfia.

A large hall was also built, The People’s University, used as an educational, social and recreational centre for Trappeto and the neighbouring towns. In addition, offices, a little house for the family of a chronic invalid, roads, sewers, a pharmacy and two more doctor’s surgeries were completed, as well as the installation of the only telephone. Thousands sent donations large and small, not only inspired by Dolci but also by the remarkable spectacle of a population revitalising itself. Also in 1952 a trust was formed charged with overseeing the irrigation of 25,000 acres of countryside, thus multiplying five times the agricultural yield. Steady financial help also came in from groups in various towns who pledged monthly contributions.

On to Partinico

In 1953 Danilo Dolci moved his headquarters to Partinico, a town of about 25,000 a few miles to the east of Trappeto and also not far from Palermo. He began here a larger survey of living conditions. Concentrating on the poorest families, he wrote, ‘We found that out of 900 families in one avenue alone, the Via della Madonna, 400 were in desperate need: 161 fathers of the 400 families were in prison, outlaws or ex-convicts; or they had been murdered. Still we found among them not one sociopath criminal. On the contrary, we met Gods Children, suffering sometimes atrociously, in hopeless plights.’

These 161 men, often with the help of their children, earned 400-500 lire (a few shillings) per day as cattle herders. But this meagre income was possible only half, or at most two-thirds, of the year. Their yielding to the temptation of surviving with their families by any and every means during the remainder of the year has been punished by the authorities in the following manner: 14 men killed, two given life imprisonment, and a total of 714 years in prison for the rest! Seventeen women have been sentenced to a total of 83 years in prison, and 43 years of house arrest or community service.

In October 1955, Dolci proposed a new strategy, urging the authorities to start essential public works, foremost of which was a dam to irrigate 20,000 more acres of land. A profound study of unemployment in this depressed region was undertaken. Daily excursions to the seaside, in good weather, were arranged for the younger children and efforts were begun to make sure they all attended school until the age of thirteen. There is today also the hope that an adult evening school and a public library can be opened, for there is neither in Partinico. Distribution of goods to those in greatest distress is still continuing.

Hunger Strike

On Sunday, January 29 1956, Danilo Dolci planned to stage a collective hunger strike on the seashore near Trappeto; it would include about 1,000 unemployed, and labour union representatives. This was to be followed on 3 February by the voluntary repairing of a main country road (trazzera), which — like such roads usually are — was made impassable by mud. This method, dubbed a ‘reverse strike’, involves great sacrifice and is a public service for the whole community.

The so-called protectors of law and order planned to stage an ambush to deal with the threatened hunger strike and public service project. After dispersing the fasting ‘brigands’, as they called them, they warned the several hundred voluntary workers under Dolci’s leadership to give up their ‘destructive work on a public area.’ Of course, Dolci refused the order in the name of ‘the right to work’ and the citizen’s responsibility to ‘make this right effective’, citing Article Four of the Italian Constitution. He and some of his followers were brutally beaten and promptly arrested, while the police dispersed the rest using their rifle butts as clubs. The gloomy prison of Ucciardone in Palermo which once housed Salvatore Giuliano’s bandits less than ten years before, became the uncomfortable winter shelter of Danilo Dolci, worthy Italian follower of Gandhi.

Gandhi’s Spirit

Let us hope the Gandhian spirit and the thus far successful methods of Danilo Dolci will prevail. The struggle commands the support of all who believe in social justice, especially we pacifists at WRI, for whom aims and means are inseparable, as Gandhi so rightly taught us. Any material gain got through the moral dereliction of either the oppressed or the oppressors and ‘not born of morally good conduct is but a fading vision and a splendid misery.’ (Emanuel Kant).

Reference: IISG/WRI Archive Box 117: Folder 2, Subfolder 1.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Giovanni Pioli was a renowned Italian scholar, pacifist, and author of the 1950s. His books were mostly on religious themes in literature, such as the Faust legend. The literature on Dolci is extensive, as is the availability of information on the web. His Wikipedia page may be consulted, and there is also a website devoted to him, in Italian and English; this article with thanks to WRI/London and their director Christine Schweitzer.