by Terry Messman

Kazu Haga is dedicated to spreading Martin Luther King’s vision of the Beloved Community to the next generation. Rev. King believed that his philosophy of nonviolent resistance could be effective not just in the struggle against segregation, but also in the struggle against militarism, and in the struggle against economic injustice.

Street Spirit: What led you to make Martin Luther King’s vision of nonviolent movement building such a central part of your activism and your life?

Kazu Haga: I took my first two-day training in Kingian Nonviolence in the fall of 2008 from Jonathan Lewis when I was living in Oakland. We were both working with an organization called The Gathering for Justice founded by Harry Belafonte. Kingian Nonviolence was to be one of the core strategies for that group.

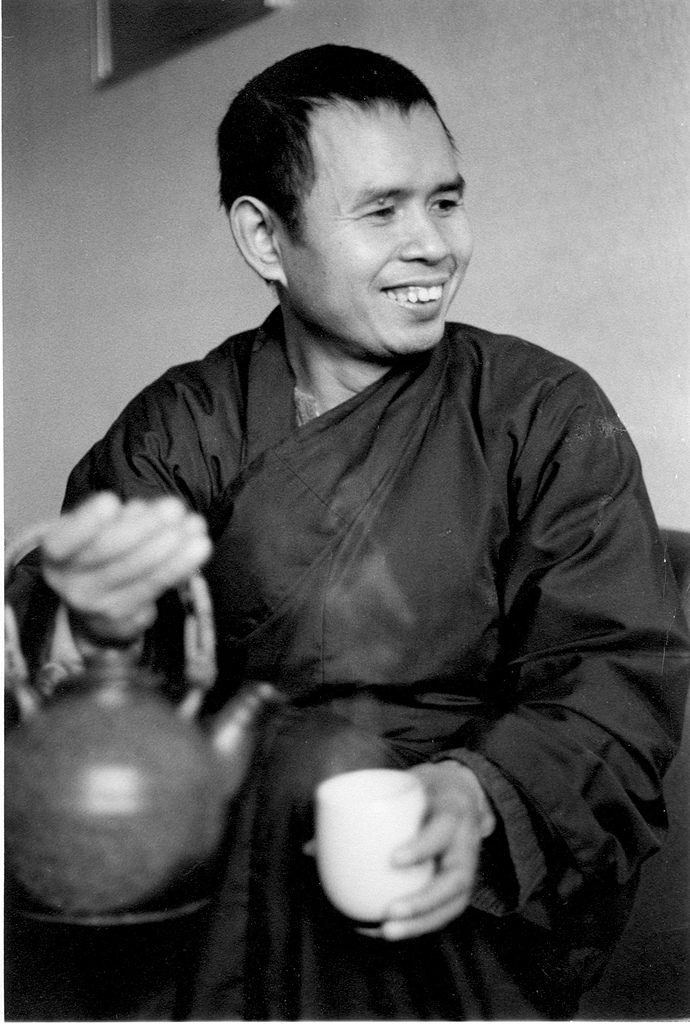

Portrait of Kazu Haga; photographer unknown

So I took the workshop from Jonathan and I told him at the time that this philosophy was something that I always knew but just didn’t have the language to articulate. Jonathan Lewis had already been working with Bernard Lafayette for about 10 years at that point.

So after I took that training, it was weighing heavily on my mind, and then about two months later, Oscar Grant was shot. [Editor’s note: Grant, an African-American man, was fatally shot by Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) police officer Johannes Mehserle in the early morning on New Year’s Day 2009 at the Fruitvale BART Station. TM]

I ended up on the steering committee of the Coalition Against Police Executions (CAPE), which was doing all the mobilizations after the shooting. So this philosophy of nonviolence was really heavy on my mind during that whole campaign and I really started to see how the anger and, at times, the hatred that was within the movement was starting to impact our work. The internal dynamics of our movement were starting to have an effect on the external impacts of the campaign.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

This is how a legacy is passed on to a new generation: Martin Luther King gave his life spreading the message of nonviolence. After he was assassinated, Bernard Lafayette picked up the fallen torch, and passed it on to Kazu Haga and Jonathan Lewis. Now they are sharing this vision with the next generation.

Kazu Haga (left) holds a nonviolence workshop; East Bay Meditation Center; Courtney Supple and Rebecca Speert listen.

Over the past year, the Positive Peace Warrior Network has conducted workshops in the strategy, philosophy, and ethical values of “Kingian Nonviolence” for more than one thousand people, including high school students, grandparents, prisoners in local jails, young people of color living in dangerous neighborhoods, Occupy activists, and organizers involved in many social change movements.

The Positive Peace Warrior Network (PPWN) defines “Positive Peace” as peace with justice for all because Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. taught that, “peace is not only the absence of violence, but the presence of justice.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

Occupy Our Homes Atlanta is a great sign of hope for all people caught up in the shattering experience of eviction. Their actions give us hope that we can overcome, no matter how powerful and well entrenched the banks may be, no matter how many lawyers and lobbyists they employ.

After Rev. King was assassinated in 1968 while organizing the Poor People’s Campaign, he was buried in Atlanta. His widow, Coretta Scott King, established the King Center in Atlanta to preserve and pass on his legacy of nonviolent resistance to the interrelated evils of poverty, racial discrimination and militarism.

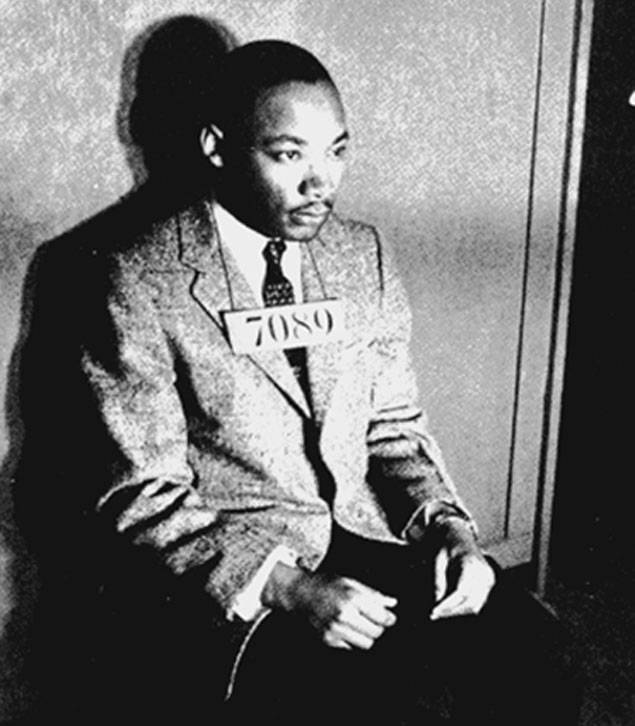

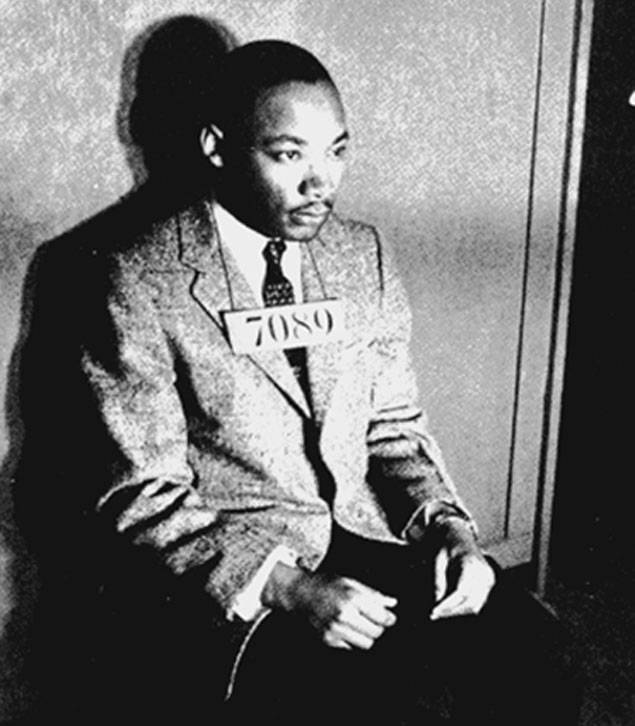

Prisoner #7089, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., mug shot taken by police after his arrest during Montgomery bus boycott.

Rev. King was assassinated while trying to mobilize poor people in a massive campaign of nonviolent resistance to secure affordable housing for all, full employment and adequate income for those unable to work; the Economic Bill of Rights for the Disadvantaged. When King was buried in Atlanta, his work was memorialized in the city of his birth, but the hopes for a Poor People’s Campaign seemingly were buried with him.

Read the rest of this article »

by Jim Forest & Nancy Forest

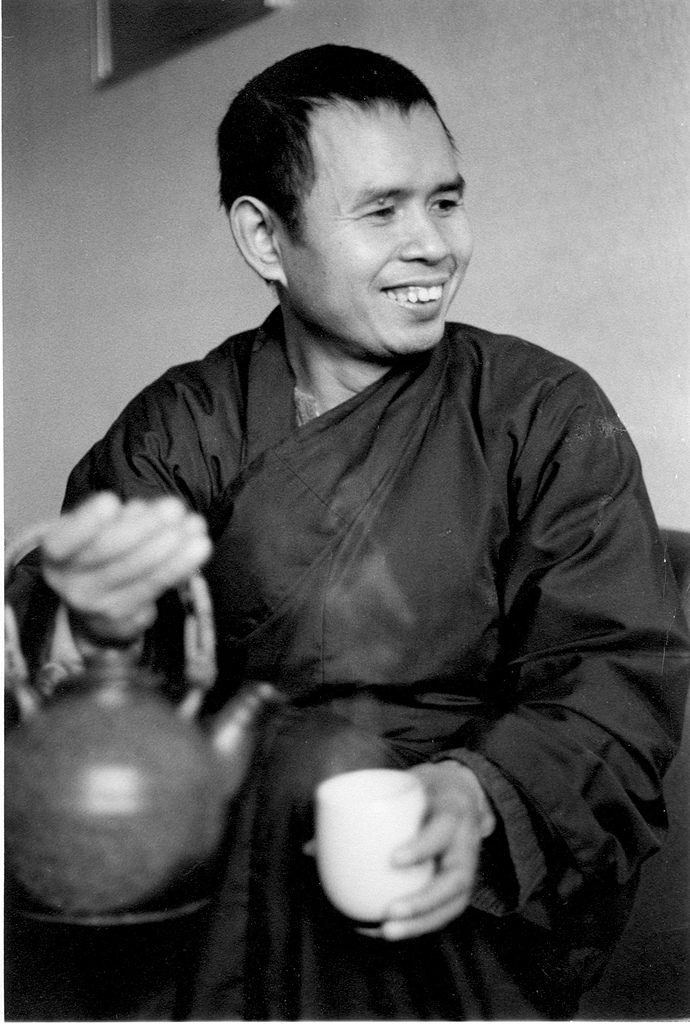

Original gelatin silver print photo by Jim Forest c. 1970.

I traveled and also at times lived with Thich Nhat Hanh in the late sixties through the seventies. Here are extracts from various letters in which Nancy and I relate a few stories about him. In these passages Nhat Hanh is sometimes called “Thay”, the Vietnamese word for teacher.

I sometimes think of an evening with Vietnamese friends in a cramped apartment in the outskirts of Paris in the early 1970s. At the heart of the community was the poet and Zen master, Thich Nhat Hanh. An interesting discussion was going on in the living room, but I had been given the task that evening of doing the washing up. The pots, pans and dishes seemed to reach half way to the ceiling on the counter of the sink in that closet-sized kitchen. I felt really annoyed. I was stuck with an infinity of dirty dishes while a great conversation was happening just out of earshot in the living room.

Somehow Nhat Hanh picked up on my irritation. Suddenly he was standing next to me. “Jim,” he asked, “what is the best way to wash the dishes?” I knew I was suddenly facing one of those very tricky Zen questions. I tried to think what would be a good Zen answer, but all I could come up with was, “You should wash the dishes to get them clean.” “No,” said Nhat Hanh. “You should wash the dishes to wash the dishes.” I’ve been mulling over that answer ever since — more than three decades of mulling.

Read the rest of this article »

by William J. Jackson

Thornton Wilder published Heaven’s My Destination in 1935, seven years after winning the Pulitzer Prize for The Bridge of San Luis Rey. The main character, George Brush, is a Depression-era twenty-three year old. He is a socially awkward naïf; he seems a simpleton to most people he meets. A traveling salesman, evangelist, and pacifist, he is at odds with general American sentiment regarding such things as money and worldly success, and he gets in trouble for proclaiming religious statements in public, often writing them on hotel desk blotters.

Front dust wrapper current edition; Harper Collins; cover photograph copyright © Getty Images

The mishaps of this misfit, his miss-steps, mistakes and misunderstandings repeatedly cause him discomfort. He is a kind of American Candide, a Don Quixote, or a Kafkaesque bumbler who never quite sees why his extreme idealism puts off so many people. Yet Brush is quite successful at selling schoolbooks, and he has a great singing voice, so he appears attractive to some people some of the time. But as soon as he begins talking about his theories and beliefs he loses people’s sympathy.

Thornton Wilder once wrote that “Art is confession; art is the secret told.” What is the “secret” expressed in the story of Heaven’s My Destination? I would suggest it is that humanity is disappointingly cynical, and our faiths only roughly approximate higher principals; they are not perfect guides, which we can force others to accept as their own. The implications of this open secret for learning as we go through life, for finding a viable path, are profound. I think this book written nearly eight decades ago tells a fable still valuable in our time, which has its own extremists. By depicting the curious antics of an extremist, it shows us what it takes to make a “true believer” begin to take idealistic teachings with a grain of practical salt. It shows that it is not wise to be too vehement in inflicting our doctrines on others, and that literalism is dangerous, causing nice people to act like fanatics.

Read the rest of this article »

by Joseph Geraci

“Grow Healthy,” South Berkeley California mural;

by Youth Spirit Artworks; photo by Ariel Messman-Rucker;

courtesy of Street Spirit.

Satyagraha Foundation (SF): In your book, Prescription for Self-Healing (“Zelfgenezing op doktersrecept”) you refer to the ancient Greek, Hippocratic origins of western medicine and the principle, that “the action of healing must avoid harm.” The Gandhian term for nonviolence, ahimsa, can be translated as, “Do no harm”. Can we also speak of ahimsa as a principle for healing?

Richard Hoofs (HOOFS): Absolutely we can apply ahimsa to healing. The first principle for a doctor or health practitioner is not to harm the patient. Every doctor swears an oath to this. The word heal, in fact, comes from the root to make whole, or to become one again, and by this I mean to reconnect with the source, to the light within. To reconnect with this source and light within is a sacred event. It is healing.

Read the rest of this article »