Statement of Purpose

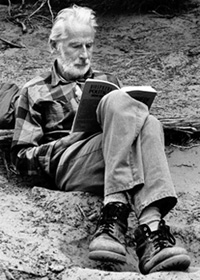

With the permission and cooperation of Mrs. Arne Naess, we are posting here Arne Naess’s Gandhian writings. We will also be posting critical writings about Naess’s Gandhian theories. See, for example, Alan Drengson’s biographical and critical article already posted.

The Norwegian philosopher Arne Naess (1912-2009) is one of the foremost environmental thinkers of the twentieth century, often referred to as “the father of deep ecology”. Less well known is that he was also a major theorist of Gandhian nonviolence, or more specifically of active nonviolent resistance, satyagraha. His two Gandhian volumes were published in small editions as Gandhi and Group Conflict: An Exploration of Satyagraha, Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1974, and Gandhi and the Nuclear Age, Totowa (New Jersey): Bedminster Press, 1965. Most of Group Conflict has been reissued as Volume V of the ten volume set, Selected Works of Arne Naess, Dordrecht: Springer Verlag, 2007, but most of Nuclear Age has until now been unavailable.

Naess’s primary philosophical work was in the area of linguistic analysis, that is, the application of mathematical set theory to the problem of interpreting language and statements we make to each other. Every statement can have several interpretations, or sets and subsets. How do we evaluate these? He was concerned with words, and with creating a new language for his environmental thinking; he coined the term ecosophy, from the Greek words for environment and wisdom, to describe his belief that every living being, whether plant, animal, or person, has the right to live and blossom, to self-realization. Gandhi had coined the word satyagraha. Naess felt an immediate affinity.

Naess was highly critical of environmentalists who did not seek to address the institutional or systemic causes of environmental destruction, or seek to change this. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) made a deep impact on him, and soon after reading it he undertook a thorough study of Gandhi’s theory of nonviolent active resistance, seeing in satyagraha a possible strategy for effectively confronting the system. Naess’s insight was that Gandhian nonviolent active resistance could be synthesized with deep ecology. This Gandhian side of Naess’s thinking, while acknowledged, is not well enough known or debated. He was a major interpreter and theoretician of satyagraha, on a par with Joan Bondurant and Krishnalal Shridharani. His reinterpretation of the meaning of Gandhian strategies in the various essays we present here is among the most trenchant discussions of Gandhi’s activist nonviolent philosophy.