by M. P. Mathai

Tree hugging photograph; courtesy spiritualecology.org

The ecological crisis we confront today has been analysed from various angles, and scientific data on the state of our environment are readily available. Humanity has come out of its foolish self-complacency and has awakened to the realisation that over-exploitation of nature has led to a very severe degradation and devastation of our environment. Scholars, through joint studies and research projects, have brought out the direct connection between consumption and environmental degradation. For example, professor of planning and development, Inge Ropke, has raised pertinent questions in his paper, “The Dynamics of the Willingness to Consume”: Why are productivity increases largely transformed into income increases instead of more leisure? Why is such a large part of these income increases used for consumption of goods and services with a relatively high materials-intensity instead of less material-intensive alternatives?

Read the rest of this article »

by Asha Devi Aryanayakam

Editor’s Preface: This article is taken from The War Resister, issue 92, Third Quarter 1961. We have posted a number of other articles on Shanti Sena, which may be accessed via our search function. Notes about the author, references, and acknowledgments are found at the end. JG

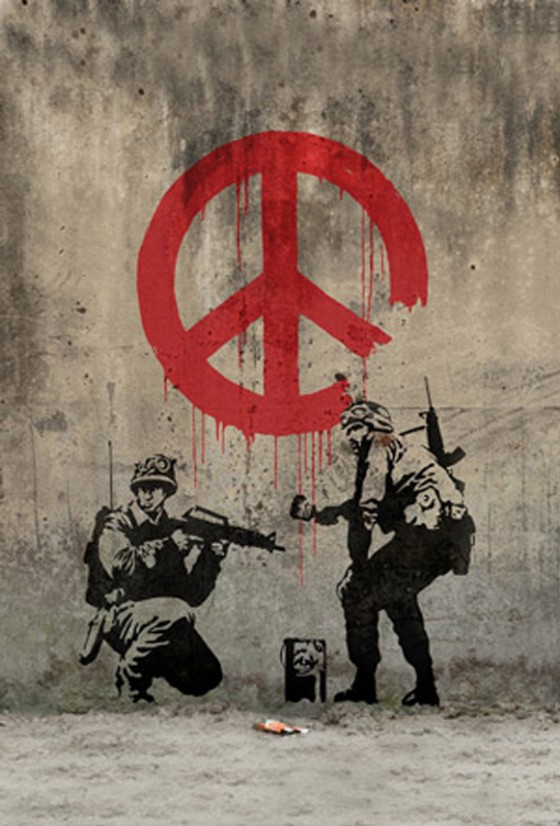

“Soldiers Painting Peace”; mural by Banksy; courtesy stencilrevolution.com

The conception of a Peace Brigade or a Peace Army was first placed before the Indian people by Gandhi in 1938. He was then engaged in the great experiment of reconstructing Indian national life through nonviolence. The movement for political independence was only a part of the story. The monster of communal tension had just begun to rear its ugly head and the Peace Army was Gandhi’s answer to the problem. With his characteristic straightforwardness, he placed his proposal in down-to-earth practical terms without any philosophical introduction.

As he wrote, ‘Some time ago I suggested the formation of a Peace Brigade (Shanti Sena), whose members would risk their lives in dealing with riots, especially communal. The idea was that this brigade should substitute for the police and even the military. This sounds ambitious. The achievement may prove impossible.’

Gandhi then suggested qualifications for the volunteers, which are mentioned by Donald Groom in his contribution to this issue of the War Resister [posted below under this date]. As Gandhi wrote, ‘Let no one understand from the foregoing that a nonviolent army is open only to those who strictly enforce in their lives all the implications of nonviolence. It is open to all those who accept the implications and make an ever increasing endeavour to observe them. There never will be an army of perfectly nonviolent people. It will be formed of those who will honestly endeavour to observe nonviolence.’ (Harijan, 21.7.1940.)

Read the rest of this article »

by Donald G. Groom

Editor’s Preface: This article is taken from The War Resister, issue 92, Third Quarter 1961. We have posted a number of other articles on Shanti Sena, which may be accessed via our search function. Notes about the author, references, and acknowledgments are found at the end. JG

“Shanti/Peace” in Sanskrit; courtesy palmstone.com

In my view there are two main aspects of the World Peace Brigade, that of individual and group action carrying out service or direct peace action; the other the supporting action of thousands and millions who have heartfelt sympathy with its purposes. All will have faith in the revolutionary power of love and compassion in all spheres of human activity and in the innate goodness of man, even though the upholding of this faith may involve suffering and death. But those people who are chosen for direct involvement in the problems of human suffering, tension, fear and all forms of violence would have to function at a different level and demonstrate the power of nonviolence for peacemaking which could only come through a high quality of life and discipline. What is expected therefore from such volunteers?

Read the rest of this article »

by Max Cooper

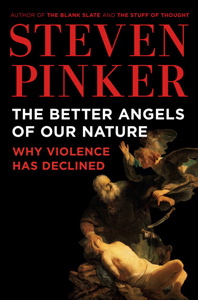

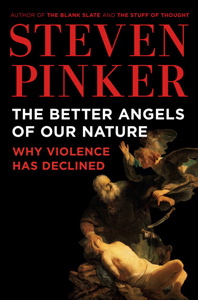

Cover art courtesy stevenpinker.com

Amongst the scores of letters he attended to every day, Mahatma Gandhi responded to one V.N.S. Chary, on April 9, 1926. Chary’s original letter does not survive, but we may reconstruct from the Mahatma’s response that he raised a particular existential question that has long troubled many practitioners of nonviolence: Is overcoming violence really possible? Is violence not simply an ineluctable feature of embodied existence and human nature? Questions in this spirit have a long history, having been explored by thinkers such as Heraclitus, Freud, Nietzsche, and others, who have often emphasized the essential duality of worldly existence – of the mutual necessity of opposites – for good to exist, so must evil; to know peace, perhaps we must know violence.

In his letter, Mr. Chary appears to have cited examples from the animal world: Hawks eat snakes; snakes eat lizards; lizards eat cockroaches, who themselves eat ants. This violence is simply natural, and it occurs perhaps for a greater good. If beings did not eat other beings, life on earth would not be possible. Beyond Chary’s points, we might also reflect that even our own human bodies are unavoidably violent; besides periodically crushing or inhaling insects unawares, our own white blood cells are constantly exterminating malignant bacteria; if they failed to kill these bacteria, we would die. Is violence not necessary for life, and should we not see it as unreasonable, or indeed impossible, to hope for a renunciation of violence?

Read the rest of this article »

by Alex Supron

Editor’s Preface: The University of Rhode Island Center for Nonviolence and Peace Studies holds an annual Gandhi Essay Contest for all Rhode Island eighth graders (c. ages 13-14). The essay below, by eighth grader Alex Supron of St. Michael’s Country Day School in Newport, Rhode Island, won first place in the 2012-2013 competition. His essay was selected from a field of 88 entries with 21 finalists. Please see the Editor’s Note at the end for links and further information. JG

Photo of Alex Supron; courtesy web.uri.edu

“Service is not possible unless it is rooted in love and ahimsa. The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in service to others.” This was a tenet of Mahatma Gandhi, one of the greatest leaders in history. Gandhi believed that by living a life focused beyond your own personal needs you are able to better serve humanity and make the world a better place.

He was not alone in these beliefs. Many great leaders throughout history have touted the importance of serving others. Confucius said: “He who wishes to secure the good of others, has already secured his own.” Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was greatly inspired by Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence and belief in the importance and satisfaction of serving. He felt that if the world were to change it would take the efforts of many: “ Everybody can be great because anybody can serve.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Rev. Scotty McLennan

Portrait of the Dalai Lama; courtesy the-open-mind.com

Editor’s Preface: This interview was conducted on November 4, 2005, at Heyns Lecture Memorial Church, Stanford University, under the auspices of the Aurora Forum. Scotty McLennan is Dean for Religious Life at Stanford University, Palo Alto, California. Please consult the note at the end for links concerning the Dalai Lama, and Aurora Forum. JG

Rev. Scotty McLennan: Why should one be nonviolent?

Dalai Lama: Why is there destruction? If we analyze its opposite — construction — we realize that we love creation and growth. Even something like a flower with no consciousness is a living thing, whenever we see flowers growing, we feel happy. Furthermore, we are a part of nature. Monkeys in trees still better. We prefer real flowers than artificial flowers. Therefore, we love living things. When we destroy living things, that’s violence. So we practice nonviolence.

Read the rest of this article »

by Vinay Lal

Illustration courtesy mayapur.com

More so than any other major political figure of modern times, Mohandas Gandhi was a man of religion – though perhaps not in the most ordinary sense of the term. No political figure of the last few hundred years brought religion, or more properly the religious sensibility, into the public domain as much as Gandhi. He concluded his autobiography, first published in 1927, with the observation that those who sought to disassociate politics and religion understood the meaning of neither politics nor religion. Indeed, the most pointed inference we can draw from Gandhi’s life is the following: the only way to be religious at this juncture of human history is to engage in the political life, not politics in the debased sense of party affiliations, or the politics that one associates with being conservative or liberal, but politics in the sense of political awareness. After Gandhi, we must clearly understand, as did Arnold Toynbee and George Orwell, that the saint’s religiosity can only be tested in the slums of life.

Read the rest of this article »

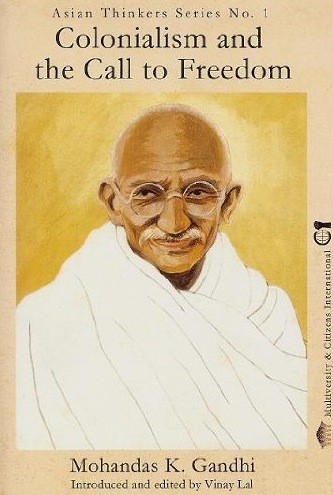

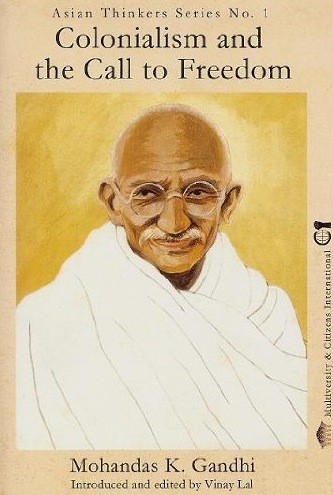

by Vinay Lal

Cover art courtesy Vinay Lal

The enterprise of making a nation is fraught with violence. People have to be not merely cajoled but browbeaten into submission to become proper subjects of a proper nation-state. Overt violence may not always play the primary role in producing the homogenous subject, but social phenomena such as schooling cannot be viewed merely as innocuous enterprises designed to ‘educate’ subjects of the state. One of the most widely cited works to have put forward this argument with elegance and scholarly rigor is Eugen Weber’s Peasants into Frenchmen, where one learns, with much surprise, that even in the Third Republic, “French was a foreign language for half the citizens.” The making of France entailed not only the modernization of the rural countryside but creating, often with violence, proper subjects of a proper nation-state. The making of the United States offers another narrative of the role of violence in the production of the nation-state, with the extermination of Native Americans long before and much after the ‘Revolutionary War’ constituting the most vital link in the long chain of violence that marked the emergence of the United States.

Postcolonial thought, attentive as always to the politics of nation-making and nationalism’s complicity with colonialism, bestowed considerable attention on the various phenomena that can be accumulated under the rubric of violence; however, it had almost no time to spare for a pragmatic, ethical, or even philosophical consideration of nonviolence. The violence of the nation-state may have always been present to the mind of postcolonial theorists, but generally this was reduced to the violence of the colonizer. One thinks, of course, of Fanon, Cesaire, Memmi, and many others in this respect. In those works that have underscored the complicity of nationalist and imperialist thought, a principal motif in the work (say) of Ranajit Guha, the violence of indigenous elites also came under critical scrutiny. (See, for example, Guha’s Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India, Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 1999) It is characteristic of most social thought in the West that it has been riveted on violence – here, postcolonial thought barely diverged from orthodox social science, mainstream social thought, or the general drift of humanist thinking. Nonviolence is barely present in intellectual discussions. We see here history’s continuing enchantment with ‘events’; nonviolence creates little or no noise, it merely is, it only fills the space in the background.

Read the rest of this article »

by Devi Prasad

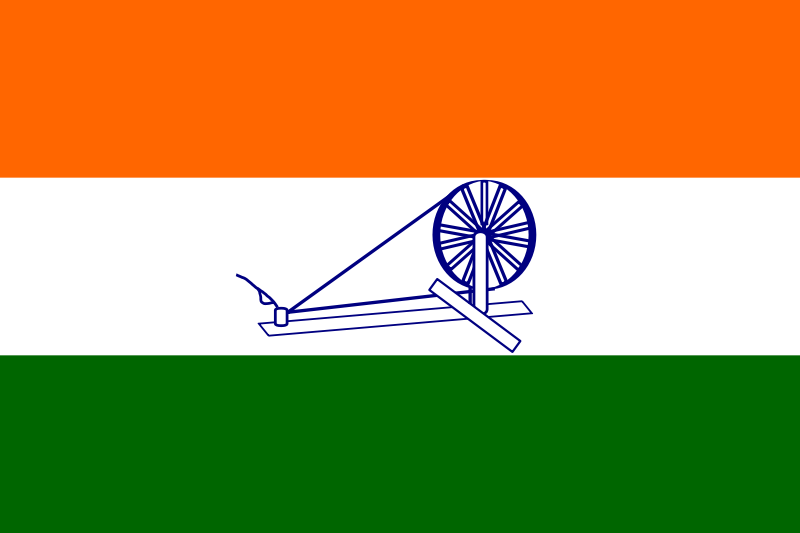

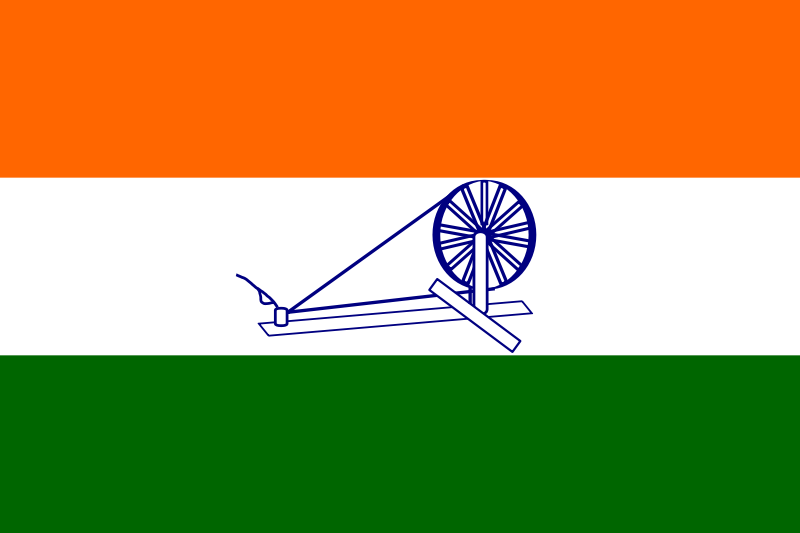

Gandhi’s “Swaraj Flag”, 1931; courtesy en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flag_of_India

Mahatma Gandhi’s concept of freedom is illustrated by that statement in which he clearly said that India would truly be free when freedom reaches the door of the most dilapidated hut in the poorest village of the country. He said that when the British leave the country, swaraj (freedom) will of course reach New Delhi, but until it goes to every hut, and every village feels freedom (swaraj) in his own life, it will not be of much meaning. What he meant was that until the common man of India lives a life of dignity and fearlessness, India will not achieve the freedom of his concept. He once stated: ‘One sometimes hears it said: “Let us get the Government of India in our own hands and everything will be all right.” There could not be greater superstition than this. No nation has thus gained its independence. The splendour of the spring is reflected in every tree, the whole earth is then filled with the freshness of youth. Similarly, when the swaraj spirit has really permeated society, a stranger suddenly come upon us will observe energy in every walk of life . . . Swaraj for me means freedom for the meanest of our countrymen. I am not interested in freeing India merely from the English yoke. I am bent upon freeing India from any yoke whatsoever.’ At another occasion he said: ‘Self-government means continuous effort to be independent of government control whether it is foreign government or whether it is national.’

Read the rest of this article »

by Krishna Kumar

Gandhi poster courtesy izquotes.com

Rejection of the colonial education system, which the British administration had established in the early nineteenth century in India, was an important feature of the intellectual ferment generated by the struggle for freedom. Many eminent Indians, political leaders, social reformers and writers voiced this rejection. But no one rejected colonial education as sharply and as completely as Gandhi did, nor did anyone else put forward an alternative as radical as the one he proposed. Gandhi’s critique of colonial education was part of his overall critique of Western civilisation. Colonisation, including its educational agenda, was to Gandhi a negation of truth and nonviolence, the two values he held uppermost. The fact that Westerners had spent ‘all their energy, industry, and enterprise in plundering and destroying other races’ was evidence enough for Gandhi that Western civilisation was in a ‘sorry mess’. (1) Therefore, he thought, it could not possibly be a symbol of ‘progress’, or something worth imitating or transplanting in India.

Read the rest of this article »