Gandhi’s Concept of Freedom

by Devi Prasad

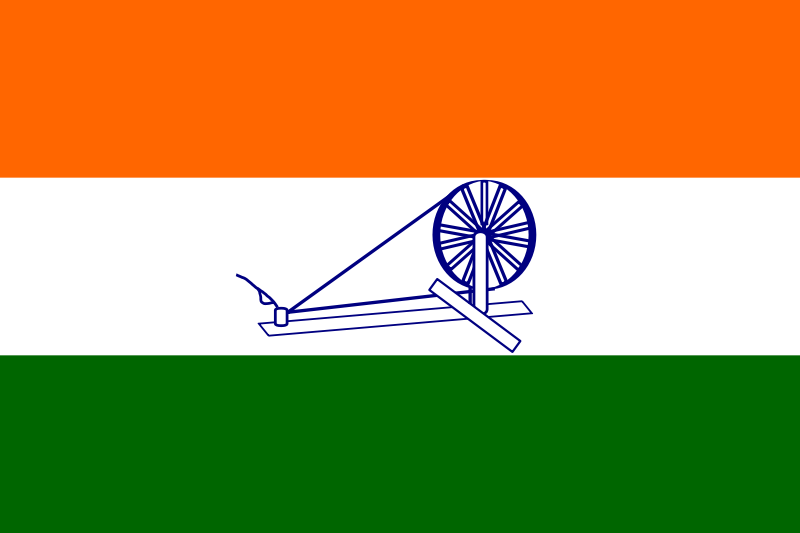

Gandhi’s “Swaraj Flag”, 1931; courtesy en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flag_of_India

Mahatma Gandhi’s concept of freedom is illustrated by that statement in which he clearly said that India would truly be free when freedom reaches the door of the most dilapidated hut in the poorest village of the country. He said that when the British leave the country, swaraj (freedom) will of course reach New Delhi, but until it goes to every hut, and every village feels freedom (swaraj) in his own life, it will not be of much meaning. What he meant was that until the common man of India lives a life of dignity and fearlessness, India will not achieve the freedom of his concept. He once stated: ‘One sometimes hears it said: “Let us get the Government of India in our own hands and everything will be all right.” There could not be greater superstition than this. No nation has thus gained its independence. The splendour of the spring is reflected in every tree, the whole earth is then filled with the freshness of youth. Similarly, when the swaraj spirit has really permeated society, a stranger suddenly come upon us will observe energy in every walk of life . . . Swaraj for me means freedom for the meanest of our countrymen. I am not interested in freeing India merely from the English yoke. I am bent upon freeing India from any yoke whatsoever.’ At another occasion he said: ‘Self-government means continuous effort to be independent of government control whether it is foreign government or whether it is national.’

Political freedom which only changed the capital from London to New Delhi, or even to the provincial capitals, was not the freedom which was Gandhi’s ultimate goal. But it is precisely what has happened in India. It is amazing how the rulers of India, who once had sacrificed everything for the freedom of their country and who in all sincerity thought that they were bringing freedom for the common man, completely failed in their objectives. The mere facts that the youth and the workers of India do not feel secure in their day-to-day lives and that the whole nation is under a colossal debt, and has no courage openly and boldly to take a position in world crises, are proofs of her not maintaining the freedom, which was won under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi. Thinking of the ever-widening gap between rich and poor, some who took part in the freedom struggle ask themselves, ‘Did we go through all that just for this?’

At this stage I should point out that I have not the slightest intention to single out India or try to draw a particularly pessimistic picture, or lay particular blame on her leadership. The fact is that there is hardly any country in the world, which can honestly claim that genuine freedom, as Gandhi defined it, is being experienced by all of its citizens. In fact the trend all over the world is towards an increasing centralisation of power, resulting in growing alienation of the common man. This is evident by the way youth everywhere is reacting to the situation it lives in; be it in the affluent society or in the technologically underdeveloped countries, young people in particular feel that they are being manipulated and that there is nothing they can do to change the way society is being managed.

It is the question of power and how and by whom it is exercised. The more centralised it becomes, the more isolated the individual feels. The more isolated he feels, the more insecure he finds himself and the more aggressive his nature becomes. Under such conditions there are two courses open to him, either he should become submissive and conform to the pattern set by the authorities, thus seeking some kind of sense of security, or he should try to overcome the sense of alienation and powerlessness by non-cooperating with the system and re-establishing the kinds of human relationship which generate love and creative coexistence.

It is unfortunate that men who take the second path, the path of love and freedom, are often called unpatriotic and antisocial, only because their concept of freedom is different from the concept of freedom politicians generally have. Gandhi once said ‘Real freedom will come not by the acquisition of authority by a few, but by the acquisition of the capacity of all to resist authority when abused; in other words, freedom is to be attained by educating the people to a sense of their capacity to regulate and control authority.’

The question is ‘Who wields power?’ the people or the top stratum of society, whatever its political structure. Gandhi had the vision to pronounce that unless power reached every home, unless everybody felt that he wielded influence on the decisions made at the centres of power; in fact, unless everybody felt that he was co-responsible for the decisions made, society could never live in peace and prosperity. The truth of Gandhi’s ideas is illustrated by the fact that in spite of the technological advance, man still lives in fear and mistrust. I have seen with distress men and women behaving differently before different people only for the fear of expressing themselves freely against the power structure. Certainly that is not freedom. Brutal firing on people who gather together to express their disagreement and disapproval with government policies is an everyday occurrence in some countries. Would you call these countries free?

The point is that the common notion that what may be freedom for the individual may not be — and mostly is not — in the best interest of the society, is mistaken. Gandhi evidently did not see this conflict of interests. He said, ‘In the democracy I have envisaged . . . there will be equal freedom for all. Everybody will be his own master.’ For him the individual was the centre. ‘In this structure composed of innumerable villages there will be ever-widening, ever-ascending circles. Life will not be a pyramid with the apex sustained by the bottom, but it will be an oceanic circle whose centre will be the individual, always ready to perish for the village, the latter ready to perish for the circle of villagers till at last the whole becomes one life composed of individuals, never aggressive in their arrogance, but ever humble, sharing the majesty of the oceanic circle, of which they are integral units.’

Therefore, the outermost circumference will not wield power to crush the inner circle but will give strength to all within and derive its own strength from it. I may be taunted with the retort that this is all Utopian and therefore not worth a single thought. Let India live for the true picture, though never realisable in its completeness. We must have a proper picture of what we want before we can have something approaching it. If there ever is to be a republic of every village in India, then I claim verity for my picture in which the last is equal to the first or in other words, no one is to be the first and none the last.’

In the jungle of traditional political ideas and practices we have lost sight of the most subtle point which Gandhi made. He repeatedly said that his fight for political independence of India was only the first step towards gaining real freedom. This is because power politics does not give consideration to the growth of the individual, at least not in practice. Its major interests are maintenance of power. A full-grown individual in the Gandhian sense is in fact a threat to the present power structure. On the other hand, Gandhi saw the individual as the basic unit of a free and creative society. Even by traditional standards and values the freedom of a country cannot be defended if the society is divided and is suffering from internal fears and distrust. There are few countries, whose governments are confident in their heart of hearts that their people will fight to defend the interests of their rulers. Hence they depend on conscription. So much so, that even the values such as social service are practised by conscription. In other words modern society functions on the principles of conscription for the defence of both property and values. Once somebody asked Vinoba Bhave, the greatest living Gandhian, what differences he saw in the systems of the two greatest philosophies, Communist and Sarvodaya. One of the points he made was that, in communism, service of the society was a compulsory element of education but in sarvodaya the individual himself will feel inspired to do social service. He will consider himself educated only if he has imbibed the spirit of spontaneous service. In short, Gandhi’s society is a spontaneous and voluntary one, while all other modern societies are conscriptive.

What I have tried to say is that freedom has some sensible meaning only when it becomes a living value for everybody in the society and I want to underline the word ‘everybody’. I am sure I have not ignored the value Gandhi attached to the idea of national freedom. Nonetheless, I should perhaps mention a few points about it. He was a pioneer of the cause of people’s freedom. He was not a nationalist, although he fought for the freedom of the Indian nation. Again, that was only a step towards a much wider kind of freedom for India. Even though he liked to see a united India, he fully recognized the independence of small groups. When some leaders of the Nagaland approached Gandhi in connection with their demand for independence, he told them, ‘Nagas have every right to be independent. We did not want to live under the domination of the British and they are now leaving us. I want you to feel that India is yours. I feel that the Naga hills are mine just as they are yours, but if you say that they are not mine, the matter must stop there. I believe in the brotherhood of man, but I do not believe in force or forced unions. If you do not wish to join the Union of India, nobody will force you to do that.’ When he was told by the Naga leaders that the Indian authorities were threatening to do exactly that, he said that they were wrong They ‘cannot do that … I will come to the Naga hills. I will ask them to shoot me first before one Naga is shot.’

Gandhi’s nationalism, as I have already said, was only the first step towards achieving the feeling of brotherhood for all mankind. ‘My mission is not merely freedom of India, though today it undoubtedly engrosses practically the whole of my life and the whole of my time. But through realisation of freedom of India I hope to realise and carry on the mission of brotherhood of man. My patriotism is not an exclusive thing. It is all embracing and I should reject that patriotism which sought to mount upon the distress or exploitation of other nationalities. The conception of my patriotism is nothing, if it is not in every case, without exception, consistent with the broadest good of humanity at large.’

I come to my last point now. My freedom is not a real freedom if you are also not free. If my freedom takes away the freedom of my opponent, it is not the kind of freedom I am striving for. I know it sounds romantic or idealistic to many people but if we want to understand Gandhi and wish to draw some lessons from his experiences, this is the most important aspect of his thinking. This is his greatest contribution to mankind. It is that element in Gandhi, which compels one to explore new methods of achieving freedom, for old methods, according to him, cannot bring genuine and lasting freedom. As Gandhi said, ‘My experience, daily growing stronger and richer, tells me that there is no peace for individuals or for nations without practising truth and nonviolence to the uttermost extent possible for man. The policy of retaliation has never succeeded.’

In his typical way Gandhi does not claim that he is the originator of the doctrine of nonviolence. ‘I have, therefore, ventured to place before India the ancient law of self-sacrifice. For satyagraha and its off-shoots, non-cooperation and civil resistance, are nothing but new names for the law of suffering. The rishis (seers) who discovered the law of nonviolence in the midst of violence were greater geniuses than Newton. They were themselves greater warriors than Wellington. Having themselves known the use of arms, they realised their uselessness and taught a weary world that its salvation lay not through violence but through nonviolence.’

Gandhi fully recognised and respected the revolutionaries whose way was that of violence. But time and time again he said that nonviolence was a superior force and that it was the weapon of the brave and not of the coward. ‘I am not ashamed to stand erect before the heroic and self-sacrificing revolutionary because I am able to pit an equal measure of nonviolent men’s heroism and sacrifice untarnished by the blood of the innocent. Self-sacrifice of one innocent man is a million times more potent than the sacrifice of a million men who die in the act of killing others. The willing sacrifice of the innocent is the most powerful retort to insolent tyranny that has yet been conceived by God or man.’ The uniqueness of nonviolent means of fighting evil lie in the fact that, ‘in a nonviolent conflict there is no rancour left behind, and in the end the enemies are converted into friends. That was my experience in South Africa, with General Smuts. He started with being my bitterest opponent and critic. Today he is my warmest friend.’

I have not mentioned the various elements of Gandhi’s concept of freedom, e.g. a new economic model as an essential part of a free country, education etc. There is not time for all that. To conclude, I wish to point out that while thinking of resolving problems of our era we have to think in terms of a qualitative breakthrough and not a quantitative one. The quantitative breakthrough was achieved decades ago and it destroyed tens of thousands of innocent lives. That breakthrough continues to be an increasing threat to mankind’s survival.

What Gandhi wanted is a complete revolution in the attitude of nations. While repeatedly saying that each country must act on its own accord to change the situation and build its own freedom and freedom loving society, he put special responsibility on the big powers. ‘It is open to the great powers to take it (nonviolence) up any day and earn the eternal gratitude of posterity. If they or any of them could shed the fear of destruction if they disarmed themselves, they will automatically help the rest to regain their sanity. But then great powers have to give up imperialistic ambitions and exploitation and revise their mode of life.’ It is absolutely essential for world peace that nations learn to behave with sanity with each other. As long as big powers go on bullying small nations and dictate to them how they must behave, peace will remain only a remote possibility.

Of course the unique thing about Gandhi is that he gave a new orientation to the question of liberation. He hoped that even small nations would be able to fight with big powers with the weapon of nonviolence. In this age of nuclear, chemical and bacteriological weapons it has become even more important that new weapons which I should like to call anti-weapon weapons must be discovered. Gandhi has shown the direction. If man wants to live and live in peace and brotherhood he should learn to do so with the help of Gandhi’s ideas.

I am an optimist and to express my optimism I quote my teacher Gandhi, ‘I am an irrepressible optimist. My optimism rests on my belief in the infinite possibilities of the individual to develop nonviolence. The more you develop it in your own being, the more infectious it becomes till it overwhelms your surroundings and by and by might sweep over the world.’

Reference: IISG/WRI Archive Box 16: Folder 2, Subfolder 3.

A NOTE ON THE TEXT: This is the unpublished text of a speech Prasad gave at the WRI International Seminar, held in Budapest, 1969.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Devi Prasad (1921-2011) was a studio potter, peace activist and artist. In 1969, at the time that he delivered this speech, he was acting director of WRI. As a child he was educated at Rabindranath Tagore’s school at Shantiniketam, and in 1944 Gandhi invited him to his ashram at Sevagram to teach pottery. Besides spinning cotton and weaving cloth (khadi), the most famous of Gandhi’s methods of self-sufficiency, Gandhi also valued and encouraged the learning of all the crafts, and insisted they be included in his education system. Our thanks to WRI, and especially Christine Schweitzer, for their cooperation with our WRI project. We have also posted Prasad’s article on Gramdan.