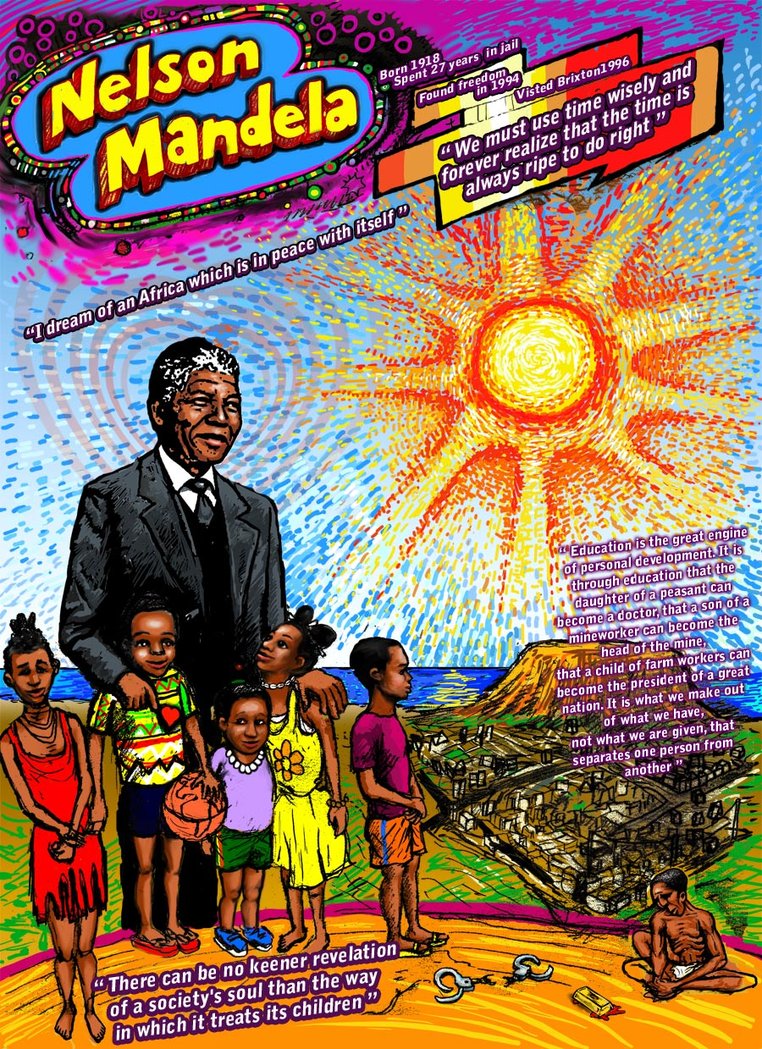

Mandela and Gandhi

by John Scales Avery

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela (1918-2013) and Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) were two of history’s greatest leaders in the struggle against governmental oppression. They are also remembered as great ethical teachers. Their lives had many similarities; but there were also differences.

Similarities

Both Mandela and Gandhi were born into politically influential families. Gandhi’s father and grandfather were dewans (prime ministers) in Porbandar, a district of the Indian state of Gujarat. Mandela’s great-grandfather was the ruler of the Thembu peoples in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. When Mandela’s father died, his mother brought the young boy to the palace of the Thembu people’s regent, Chief Jongintaba Dalindyebo, who became the boy’s guardian. He treated Mandela as a son and gave him an outstanding education.

Both Mandela and Gandhi studied law. Both were astute political tacticians, and both struggled against governmental injustice in South Africa. Both were completely fearless. Both had iron wills and amazing stubbornness. Both spent long periods in prison as a consequence of their opposition to injustice and both are remembered for their strong belief in truth and fairness, and for their efforts to achieve unity and harmony among conflicting factions. Both treated their political opponents with kindness and politeness.