The Technique of Nonviolent Action

by Gene Sharp

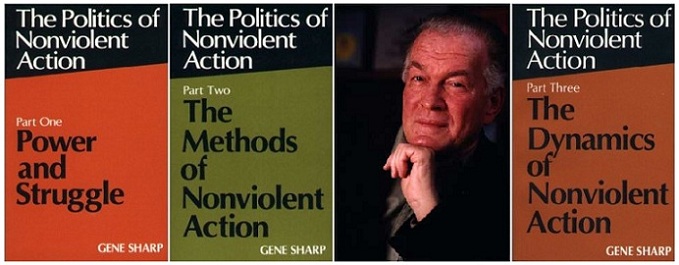

Book jacket assemblage courtesy rcnv.org

Editor’s Preface: This little known essay by Gene Sharp was discovered in the War Resisters’ International archive in a folder labeled “Ira Sandperl’s Speaking Tour of Western Europe, 1970: Background Reading.” The typescript seems to have been given to Sandperl by Sharp. We have not found any evidence that Sharp published the essay in this form, although he was to rework the material in later works, especially the section below “84 Cases of Nonviolent Action”. Sandperl was an interesting figure in the 1970s peace movement. A foremost member of the War Resisters League, (the U.S. branch of WRI), he might be better known to some as Joan Baez’s acknowledged mentor. Sandperl was also co-founder of the Peninsula Peace Center in California, which Baez also helped support. Please see the notes at the end for further information about Gene Sharp, archival references, and acknowledgments. JG

It is widely believed that military combat is the only effective means of struggle in a wide variety of situations of acute conflict. However, there is another whole approach to the waging of social and political conflict. Any proposed substitute for war in the defense of freedom must involve wielding power, confronting and engaging an invader’s military might, and waging effective combat. The technique of nonviolent action, although relatively ignored and undeveloped, may be able to meet these requirements, and provide the basis for a defense policy.

Alternative Approach to the Control of Political Power

Military action is based largely on the idea that the most effective way of defeating an enemy is by inflicting heavy destruction on his armies, military equipment, transport system, factories and cities. Weapons are designed to kill or destroy with maximum efficiency. Nonviolent action is based on a different approach: to deny the enemy the human assistance and cooperation, which are necessary if he is to exercise control over the population. It is thus based on a more fundamental and sophisticated view of political power.

A ruler’s power is ultimately dependent on support from the people he would rule. His moral authority, economic resources, transport system, government bureaucracy, army and police—to name but a few immediate sources of his power—rest finally upon the co-operation and assistance of other people. If there is general conformity, the ruler is powerful.

But people do not always do what their rulers would like them to do. The factory manager recognizes this when he finds his workers leaving their jobs and machines, so that the production line ceases operation; or when he finds the workers persisting in doing something on the job, which he has forbidden them to do. In many areas of social and political life comparable situations are commonplace. A man who has been a ruler and thought his power secure may discover that his subjects no longer believe he has any moral right to give them orders, that his laws are disobeyed, that the country’s economy is paralyzed, that his soldiers and police are lax in carrying out repression or openly mutiny, and even that his bureaucracy no longer takes orders. When this happens, the man who has been ruler becomes simply another man, and his political power dissolves, just as the factory manager’s power does when the workers no longer cooperate and obey. The equipment of his army may remain intact, his soldiers uninjured and very much alive, his cities unscathed, the factories and transport systems in full operational capacity, and the government buildings and offices unchanged. Yet because the human assistance, which had created and supported his political power, has been withdrawn, the former ruler finds that his political power has disintegrated.

Nonviolent Action

The “technique” of “nonviolent action”, which is based on this approach to the control of political power and the waging of political struggles, has been the subject of many misconceptions: for the sake of clarity the two terms are defined in this section.

The term technique is used here to describe the overall means of conducting an action or struggle. One can therefore speak of the technique of guerilla warfare, of conventional warfare, and of parliamentary democracy.

The term nonviolent action refers to those methods of protest, non-cooperation, and intervention in which the actionists, without employing physical violence, refuse to do certain things which they are expected, or required, to do; or do certain things which they are not expected, or are forbidden, to do. In a particular case there can of course be a combination of acts of omission and acts of commission.

Nonviolent action is a generic term: it includes the large class of phenomena variously called “nonviolent resistance”, “satyagraha”, “passive resistance”, “positive action”, and “nonviolent direct action”. While it is not violent, it is action, and not inaction; passivity, submission and cowardice must be surmounted if it is to be used. It is a means of conducting conflicts and waging struggles, and is not to be equated with (though it may be accompanied by) purely verbal dissent or solely psychological influence. It is not “pacifism”, and in fact has in the vast majority of cases been applied by non-pacifists. The motives for the adoption of nonviolent action may be religious or ethical, or they may be based on considerations of expediency. Nonviolent action is not an escapist approach to the problem of violence, for it can be applied in struggles against opponents relying on violent sanctions. The fact that in a conflict one side is nonviolent does not imply that the other side will also refrain from violence. Certain forms of nonviolent action may be regarded as efforts to persuade by action, while others are more coercive.

Methods of Nonviolent Action

There is a very wide range of methods, or forms, of nonviolent action, and at least 125 have been identified. They fall into three classes—nonviolent protest, non-cooperation, and nonviolent intervention.

Generally speaking, the methods of “nonviolent protest” are symbolic in their effect and produce an awareness of the existence of dissent. Under tyrannical regimes, however, where opposition is stifled, their impact can in some circumstances be very great. Methods of nonviolent protest include marches, pilgrimages, picketing, vigils, “haunting” officials, public meetings, issuing and distributing protest literature, renouncing honors, voluntary emigration, and humorous pranks.

The methods of “nonviolent non-cooperation”, if sufficient numbers take part, are likely to present the opponent with difficulties in maintaining the normal efficiency and operation of the system; and in extreme cases the system itself may be threatened. Methods of nonviolent non-cooperation include various types of strike (such as general strike, sit-down strike, industry strike, go-slow, and work-to-rule); various types of boycott (such as economic boycott, consumers boycott, traders boycott, rent refusal, international economic embargo, and social boycott); and various types of political non-cooperation (such as boycott of government employment, boycott of elections, revenue refusal, civil disobedience, and mutiny).

The methods of “nonviolent intervention” have some features in common with the first two classes, but also challenge the opponent more directly; and, assuming that fearlessness and discipline are maintained, relatively small numbers may have a disproportionately large impact. Methods of nonviolent intervention include sit-ins, fasts, reverse strikes, nonviolent obstruction, nonviolent invasion, and parallel government.

The exact way in which methods from each of the three classes are combined varies considerably from one situation to another. Generally speaking, the risks to the actionists on the one hand, and to the system against which they take action on the other, are least in the case of nonviolent protest, and greatest in the case of nonviolent intervention. The methods of non-cooperation tend to require the largest numbers, but not to demand a large degree of special training from all participants. The methods of nonviolent intervention are generally effective if the participants possess a high degree of internal discipline and are willing to accept severe repression; the tactics must also be selected and carried out with particular care and intelligence.

Several important factors need to be considered in the selection of the methods to be used in a given situation. These factors include the type of issue involved, the nature of the opponent, his aims and strength, the type of counter-action he is likely to use, the depth of feeling both among the general population and among the likely actionists, the degree of repression the actionists are likely to be able to take, the general strategy of the over-all campaign, and the amount of past experience and specific training the population and the actionists have had. Just as in military battle weapons are carefully selected, taking into account such factors as their range and effect, so also in nonviolent struggle the choice of specific methods is very important.

Mechanisms of Change

In nonviolent struggles there are, broadly speaking, three mechanisms by which change is brought about. Usually there is a combination of the three. They are conversion, accommodation, and nonviolent coercion.

George Lakey has described the “conversion” mechanism thus: “By conversion we mean that the opponent, as the result of the actions of the nonviolent person or group, comes around to a new point of view which embraces the ends of the nonviolent actor.” This conversion can be influenced by reason or argument, but in nonviolent action it is also likely to be influenced by emotional and moral factors, which can in turn be stimulated by the suffering of the nonviolent actionists, who seek to achieve their goals without inflicting injury on other people.

Attempts at conversion, however, are not always successful, and may not even be made. “Accommodation” as a mechanism of nonviolent action falls in an intermediary position between conversion and nonviolent coercion, and elements of both of the other mechanisms are generally involved. In accommodation, the opponent, although not converted, decides to grant the demands of the nonviolent actionists in a situation where he still has a choice of action. The social situation within which he must operate has been altered enough by nonviolent action to compel a change in his own response to the conflict; perhaps because he has begun to doubt the rightness of his position, perhaps because he does not think the matter worth the trouble caused by the struggle, and perhaps because he anticipates coerced defeat and wishes to accede gracefully or with a minimum of losses.

“Nonviolent coercion” may take place in any of three circumstances. Defiance may become too widespread and massive for the ruler to be able to control it by repression; the social and political system may become paralyzed; or the extent of defiance or disobedience among the ruler’s own soldiers and other agents may undermine his capacity to apply repression. Nonviolent coercion becomes possible when those applying nonviolent action succeed in withholding, directly or indirectly, the necessary sources of the ruler’s political power. His power then disintegrates, and he is no longer able to control the situation, even though he still wishes to do so.

Nonviolent Action versus Violence

There can be no presumption that an opponent, faced with an opposition relying solely on nonviolent methods, will suddenly renounce his capacity for violence. Instead, nonviolent action can operate against opponents able and willing to use violent sanctions and can counter their violence in such a way that they are thrown politically off balance in a kind of political jujitsu.

Instead of confronting the opponent’s police and troops with the same type of forces, nonviolent actionists counter these agents of the opponent’s power indirectly. Their aim is to demonstrate that repression is incapable of cowing the populace, and to deprive the opponent of his existing support, thereby undermining his ability or will to continue with the repression. Far from indicating the failure of nonviolent action, repression often helps to make clear the cruelty of the political system being opposed, and so to alienate support from it. Repression is often a kind of recognition from the opponent that the nonviolent action constitutes a serious threat to his policy or regime, one which he finds it necessary to combat.

Just as in war danger from enemy fire does not always force front line soldiers to panic and flee, so in nonviolent action repression does not necessarily produce submission. True, repression may be effective, but it may fail to halt defiance, and in this case the opponent will be in difficulties. Repression against a nonviolent group which persists in face of it and maintains nonviolent discipline may have the following effects: it may alienate the general population from the opponent’s regime, making them more likely to join the resistance; it may alienate the opponent’s usual supporters and agents, and their initial uneasiness may grow into internal opposition and at times into non-cooperation and disobedience; and it may rally general public opinion (domestic or international) to the support of the nonviolent actionists; though the effectiveness of this last factor varies greatly from one situation to another, it may produce various types of supporting actions. If repression thus produces larger numbers of nonviolent actionists, thereby increasing the defiance, and if it leads to internal dissent among the opponent’s supporters, thereby reducing his capacity to deal with the defiance, it will clearly have rebounded against the opponent.

Naturally, with so many variables (including the nature of the contending groups, the issues involved, the context of the struggle, the means of repression, and the methods of nonviolent action used), in no two instances will nonviolent action “work” in exactly the same way. However, it is possible to indicate in very general terms the ways in which it does achieve results. It is, of course, sometimes defeated: no technique of action can guarantee its user short-term victory in every instance of its use. It is important to recognize, however, that failure in nonviolent action may be caused, not by an inherent weakness of the technique, but by weakness in the movement employing it, or in the strategy and tactics used.

Strategy is just as important in nonviolent action as it is in military action. While military strategic concepts and principles cannot be automatically carried over into the field of civilian defense, since the dynamics and mechanisms of military and nonviolent struggle differ greatly, the basic importance of strategy and tactics is in no way diminished. The attempt to cope with the variety of strategic and tactical problems, associated with the application of civilian defense, needs to be based on thorough consideration of the particular dynamics and mechanisms of nonviolent struggle, and on consideration of the general principles of strategy and tactics appropriate to the technique—both those peculiar to it and those which may be carried over from the strategy of military and other types of conflict.

The Indirect Approach to the Opponent’s Power

The technique of nonviolent action, and the policy of civilian defense relying upon it, can be regarded as extreme forms of the “strategy of indirect approach” which Liddell Hart has propounded in the sphere of military strategy. He has argued that a direct strategy—confronting the opponent head-on—consolidates the opponent’s strength. “To move along the line of natural expectation consolidates the opponent’s balance and thus increases his resisting power.” An indirect approach, he argues, is militarily more sound, and generally effective results have followed when the plan of action has had “such indirectness as to ensure the opponent’s unreadiness to meet it”. “Dislocation” of the enemy is crucial, he insists, to achieve the conditions for victory, and the dislocation must be followed by “exploitation” of the opportunity created by the position of insecurity. It thus becomes important “to nullify opposition by paralyzing the power to oppose”, and to make “the enemy do something wrong”.

These general, and at first glance abstract, principles of strategy can take a concrete form not only in certain types of military action, but also in nonviolent action, and therefore in civilian defense. An invader, or other usurper, is likely to be best equipped to apply, and to combat, military and other violent means of combat and repression. Instead of meeting him directly on that level, nonviolent actionists and civilian defenders rely on a totally different technique of struggle, or “weapons system”. The whole conflict takes on a very special character: the combatants fight, but with different weapons. Given an extensive, determined and skilful application of nonviolent action, the opponent is likely to find that the nonviolent actionists’ insistence on fighting with their chosen “weapons system” will cause him very special problems which frustrate the effective utilization of his own forces. As indicated above, the opponent’s unilateral use of violent repression may only increase the resistance and win new support for the resisters; and even the opponent’s supporters, agents and soldiers may first begin to doubt the rightness of his policies, and finally undertake internal opposition.

The use of nonviolent action may thus reduce or remove the very sources of the opponent’s power without ever directly confronting him with the same violent means of action on which he had relied. The course of the struggle may be viewed as an attempt by the nonviolent actionists to increase their various types of strength, not only among their usual supporters but also among third parties and in the opponent’s camp, and to reduce by various processes, the strength of the opponent. This type of change in the relative power positions will finally determine the outcome of the struggle.

Success in nonviolent struggle depends to a very high degree on the persistence of the nonviolent actionists in fighting with their own methods, and opposing all pressures—whether caused by emotional hostility to the opponent’s brutalities, temptations of temporary gains, or agents provocateurs employed by the opponent (of which there have been examples)—to fight with the opponent’s own, violent, methods. Violence by, or in support of, their side will sharply counter the operation of the very special mechanisms of change in nonviolent action—even when the violence is on a relatively small scale, such as rioting, injury, violent sabotage involving loss of life, or individual assassinations. The least amount of violence will, in the eyes of many, justify severe repression, and it will sharply reduce the tendency for such repression to bring sympathy and support for the nonviolent actionists; and it may well, for several reasons, reduce the number of resisters. Violence will also sharply reduce sympathy and support in the opponent’s own camp.

The use of violence by, or in support of, the resisters, has many effects. Its dangers are indicated by, among other things, examination of the likely effect on the opponent’s soldiers and police, who may have become sympathetic to the resisters and reluctant to continue as opposition agents. It is well known that ordinary soldiers will fight more persistently and effectively if it is a matter of survival, and if they and their comrades are being shot, bombed, wounded or killed. Soldiers and police acting against a nonviolent opposition and not facing such dangers may at times be inefficient in carrying out repression—for example by slackness in searches for “wanted” resisters, firing over the heads of demonstrators, or not shooting at all. In extreme cases they may openly mutiny. When such inefficiency or mutiny occurs, the opponent’s power is severely threatened: this will often be an objective of nonviolent actionists or civilian defenders.

The introduction of violence by their side, however, will sharply reduce their chances of undermining opposition loyalty, as the influences producing sympathy are removed and their opponents” lives become threatened. This is simply an illustration of the point that it is very dangerous to believe that one can increase one’s total combat strength by combining violent sabotage, assassinations, or types of guerilla or conventional warfare, with civilian defense, which relies on the very different technique of nonviolent action.

Development of the Technique

Nonviolent action has a long history, but because historians have often been more concerned with other matters much information has undoubtedly been lost. Even today, this field is largely ignored, and there is no good history of the practice and development of the technique. But it clearly began early. For example, in 494 BC the plebeians of Rome, rather than murder the Consuls, withdrew from the city to the Sacred Mount where they remained for some days, thereby refusing to make their usual contribution to the life of the city, until an agreement was reached pledging significant improvements in their life and status.

A very significant pre-Gandhian expansion of the technique took place in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The technique received impetus from three groups during this period: first, from trade unionists and other social radicals who sought a means of struggle—largely strikes, general strikes and boycotts—against what they regarded as an unjust social system, and for an improvement in the condition of working men; secondly, from nationalists who found the technique useful in resisting a foreign enemy—such as the Hungarian resistance against Austria between 1850 and 1867, and the Chinese boycotts of Japanese goods in the early twentieth century; and thirdly, on the level of ideas and personal example, from individuals, such as Leo Tolstoy in Russia and Henry David Thoreau in the USA, who wanted to show how a better society might be created.

While the use of nonviolent action by trade unionists and nationalists contributed significantly to its development, little attention was given to the refinement and improvement of the technique. Nonviolent action remained, with some exceptions, essentially passive—a counter-action to the opponent’s initiatives. Religious groups like the early Quakers had practiced nonviolent action as a corporate as well as an individual reaction to persecution; but the corporate practice of this technique by non-religious groups was almost unrelated to the idea that nonviolent behavior was morally preferable to violent behavior.

With Gandhi’s experiments in the use of nonviolent action to control rulers, alter policies, and undermine political systems, the character of the technique was broadened and refinements were made in its practice. Many modifications were introduced: greater attention was given to strategy and tactics; the armory of methods was expanded; and a link was consciously forged between mass political action and the ethical principle of nonviolence. Gandhi, with his political colleagues and fellow-Indians, demonstrated in a variety of conflicts in South Africa and India that nonviolent struggle could be politically effective on a large scale. He termed his refinement of the technique “satyagraha”, meaning roughly insistence and reliance upon the power of truth. “In politics, its use is based upon the immutable maxim that government of the people is possible only so long as they consent either consciously or unconsciously to be governed.” While he sought to convert the British, he did not imagine that there could be an easy solution, which would not necessitate struggle and the exercise of power. Just before the beginning of the 1930-1 civil disobedience campaign he wrote to the Viceroy:

“It is not a matter of carrying conviction by argument. The matter resolves itself into one of matching forces. Conviction or no conviction, Great Britain would defend her Indian commerce and interests by all the forces at her command. India must consequently evolve force enough to free herself from that embrace of death.”

Since Gandhi’s time, the use of nonviolent action has spread throughout the world at an unprecedented rate. In some cases it was stimulated by Gandhi’s thought and practice, but where this was so the technique was often modified in new cultural and political settings; in these cases it has already moved beyond Gandhi.

Quite independently of the campaigns led by Gandhi, important nonviolent struggles emerged under exceedingly difficult circumstances in Nazi-occupied and Communist countries: nonviolent action was used to a significant extent in the Norwegian and Danish resistance in the Second World War, in the East German uprising in 1953, in the Hungarian revolution in 1956, and in the strikes in the Soviet political prisoner camps, especially in 1953. There have been other important developments in Africa, Japan, and elsewhere. There have, of course, been setbacks, and the limited and sporadic use of nonviolent action in South Africa, for example, has been followed by advocacy of violence. However, when seen in historical perspective, there is no doubt that the technique of nonviolent action has developed very rapidly in the twentieth century.

In this same perspective, it is only recently that nonviolent resistance has been seen as a possible substitute for war in deterring or defeating invasion and other threats. It is even more recently that any attempt has been made to work out this policy—now called “civilian defense”—in any detail, and that an examination of its merits and problems has been proposed.

It is inconceivable that any country will in the foreseeable future permanently abandon its defensive capacity. Threats—some genuine, some exaggerated—are too real to people; there has been too much aggression and seizure of power by dictators to be forgotten. But while defense and deterrence inevitably rely on sanctions and means of struggle, there is much reason for dissatisfaction with the usual military means. The question therefore arises whether there exists an alternative means of struggle, which could be the basis of a new defense policy. Nonviolent action is an alternative means of struggle: in this, it has more in common with military struggle than with conciliation and arbitration. Could there then be a policy of civilian defense, which relies on this nonviolent technique? The question must be answered, not in terms of philosophy and dogma, but in the practical examination of concrete strategies through which it might operate, the problems, which might be faced, and alternative ways in which these might possibly be solved. All this will depend to a large degree on an understanding of the technique of nonviolent action, its methods, dynamics, mechanisms, and requirements.

84 Cases of Nonviolent Action

The technique of nonviolent action has been more widely practiced than is generally recognized; the following list of cases of nonviolent action should make this clear. The list should also indicate—if there is still doubt—that nonviolent action is not simply an individual phenomenon, but a technique of action capable of making a powerful social and political impact. It is cases such as these, which could serve as source material for research into the nature of nonviolent action and the validity of the claim that this technique can provide a functional substitute for violent conflict. The list is by no means exhaustive, nor is it either geographically or historically representative. Despite its inadequacy, it may nevertheless have an interim value as the most complete one to date.

There are many wide variations among the cases listed here: for example, in the number of participants, the degree of conscious commitment to nonviolence, the relative importance of a distinguishable leadership, the type of opponent faced, the amount of repression applied, and the objectives sought.

After each item there is an indication of the nature of the group applying the technique. In two cases the action was taken by a single individual, Gandhi, but had a major social and political effect and reduced reliance on violent conflict. These cases are indicated by “IND”. In six cases small highly committed groups took action, usually of less than fifty persons. These cases are indicated by “SM”. In the vast majority of cases, however, the action was taken by a large group, from fifty to many thousands of people. These cases are indicated by “LG”. These three classes were all characterized by a reliance (deliberate or accidental, principled or expedient) on nonviolent action as a part of what might be called a “grand strategy”: the substitution of nonviolent action for violent conflict was almost or fully complete.

There remains, however, a small group of seven or eight cases in which the substitution of nonviolent for violent conflict was not complete. In these cases—the Norwegian and Danish resistance during the Nazi occupation, for instance, and the Hungarian revolution— violence was not excluded on the basis of either principle or “grand strategy”, and violent methods were used to a significant extent. However, in these cases nonviolent action was also used to a significant extent—up to, say, at least fifty per cent of the total “combat strength”. These cases involved the use of nonviolent means of active struggle, such as strikes and non-cooperation. In particular phases of these cases, nonviolent action was used almost exclusively—as for example in the resistance of the teachers and clergy in Norway, and the general strikes in Copenhagen and Amsterdam. Had such nonviolent means not been used in these cases, there might have been a relatively greater application of violent methods of conflict, or a reduction of the total “combat strength”. These mixed cases are indicated by “MX”.

The eighty-four cases are classified under headings indicating the type of grievance felt by the group using nonviolent action. In several cases there is overlapping and a given case could also be listed under another heading.

A. Against Oppression of Minorities

- Civil resistance struggles by Indian minority in South Africa, 1906-14 and 1946. LG.

- Vykom temple road satyagraha (India), 1924-5. SM.

- Various campaigns in US civil rights movement, especially from 1955, such as Montgomery, Alabama, Negroes’ bus boycott, 1955-6; Tallahassee, Florida, Negro bus boycott, 1956; sit-ins; and freedom rides, 1961-2; the 1963 march on Washington, DC; and other cases. LG.

- Civil resistance by Tamils in Ceylon, 1956-7, etc., and 1961. LG.

B. Against Exploitation and Other Economic Grievances

- Mysore (India) non-cooperation, 1830. LG.

- Irish rent strike and tax refusal, 1879-86. MX.

- Boycott of Captain Boycott by Irish peasants, 1880. LG.

- Buck’s Stove and Range boycott (US), 1907. LG.

- British general strike, 1926. LG.

- US sit-down strikes, 1936-7. LG.

- French sit-down strikes, 1936-7. LG.

- “Reverse strikes”, various cases in Italy, at least since 1950, including mass fast and reverse strike in Sicily led by Danilo Dolci, 1956. LG.

- General strike in Gambia, January 1961. LG.

- Spanish workers strikes in the Asturias mines and elsewhere, 1962. LG.

(Many other cases of strikes and boycotts could be included here, and would greatly add to the number of cases of use of the technique in the West.)

C. Against Communal Disorders

- Gandhi’s fast in Calcutta, 1947. IND.

- Gandhi’s fast in Delhi, 1948. IND.

D. On Religious Issues

- Early Christian reaction to Roman persecution. LG.

- Early Quaker resistance to persecution in England, late seventeenth century. LG.

- Roman Catholic struggle vs. Prussian Government over mixed marriages, 1836-40. LG.

- Roman Catholic resistance vs. Bismarck in Kulturkampf (conflict of civilizations), 1871-87 (though concessions began in 1878). LG.

- Khilafat (Caliphate) satyagraha (India), 1920-2. LG.

- Akali Sikhs’ reform satyagraha (India), 1922. LG.

- South Vietnam Buddhist campaign vs. Ngo regime, 1963. LG.

E. Against Particular Injustices and Administrative Excesses

- Economic boycotts and tax refusal in American colonies, 1763-76. LG.

- Quebec farmers and villagers’ non-cooperation with the British corvee system, 1776-8. LG.

- Persian anti-tobacco tax boycott, 1891. LG.

- German Social Democrats’ struggle vs. Bismarck, 1879-90. LG.

- Belgian general strikes for broader suffrage, 1893, 1902 and 1913. LG.

- Swedish three-day general strike for extension of suffrage, 1902. LG.

- English tax-refusal vs. tax aid for private schools, 1902-14. LG.

- Chinese anti-Japanese boycotts in 1906, 1908, 1915 and 1919. LG.

- “Free speech” campaign by Industrial Workers of the World in Sioux City, Iowa, 1914-5. LG.

- Kheda (India) peasants’ resistance, 1918. LG.

- Peasants’ passive resistance in USSR, post-1918. LG.

- Rowlatt Act satyagraha (India), 1919. LG.

- Bardoli (India) peasants’ revenue refusal, 1928. LG.

- Pardi (India) satyagraha, 1950. LG.

- Manbhum, Bihar (India), resistance movement, 1950. LG.

- Nonviolent seizure of Heligoland from RAP, 1951. SM.

- South Indian Telugu agitation for new state of Andra, pre-1953. LG.

- Political prisoners’ strike at Vorkuta, USSR, 1953. LG.

- Finnish general strike, 1956. LG.

- African bus boycotts in Johannesburg, Pretoria, Port Elizabeth and Bloemfontein, 1957. LG.

- Kelala (India) nonviolent resistance vs. elected Communist government’s education policy, etc., 1959. LG.

- Argentine general strike, 1959. LG.

- Belgian general strike, 1960-1. LG.

F. Against War and War Preparations

- New Zealand anti-conscription struggles, 1912-4 and 1930. LG.

- Argentine general strike vs. possible entry into World War I, 1917. LG.

- French, English and Irish dock workers’ strike against military intervention in Russia, 1920. LG.

- League of Nations economic sanctions vs. Italy during war on Abyssinia, 1935-6. LG.

- Japanese resistance to constructing a US air base at Sunakawa, 1956. LG.

- Voyages of the Golden Rule and Phoenix, 1958, and of Everyman I and Everyman II, 1962, in efforts to stop US nuclear tests in the Pacific; and of Everyman III against Soviet nuclear tests, 1962. SM.

- Various cases of civil disobedience and other nonviolent action in Britain in support of nuclear disarmament, organized by the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War and the Committee of 100, 1958-63. SM and LG.

- Attempted “invasion” to prevent atomic test at Reggane, French North African atomic testing site, 1959-60. SM.

- Various cases of civil disobedience and other nonviolent action in the US, largely organized by the Committee for Nonviolent Action, 1959-66. SM and LG.

- Demonstration, threat of general strike, and various acts of intervention, to forestall new civil war in Algeria, August-September 1962. LG.

G. Against Long-established Undemocratic Rule

- Roman plebeians vs. patricians, 494 BC. LG.

- Major aspects of Netherlands resistance vs. Spanish rule, especially 1565-76. MX.

- Hungarian passive resistance vs. Austria, 1850-67. LG.

- Finnish resistance to Russian rule, 1898-1905. LG.

- Major aspects of 1905 revolution in imperial Russia, including general strikes, parallel government, and various types of non-cooperation. MX.

- Korean national protest vs. Japanese rule, 1919-22. LG.

- Egyptian passive resistance vs. British rule, 1919-22. LG.

- Western Samoan resistance vs. New Zealand rule, 1919-36. LG.

- Indian independence struggle, especially campaigns of 1930-1. 1932-4, 1940-1 and 1942. LG.

- General strike in El Salvador vs. Martinez dictatorship, 1944. LG.

- General strike in Guatemala vs. Ubico regime, 1944. LG.

- South African defiance campaign, 1952. LG.

- East German uprising, June 1953. LG and MX.

- Nonviolent “invasion” of Goa, 1955. LG.

- General strike and economic shutdown vs. Haitian strongman General Magliore, 1956. LG.

- Major aspects of the Hungarian revolution, 1956-7. MX.

- Barcelona and Madrid bus boycotts, 1957. LG.

- Nonviolent resistance to British rule in Nyasaland, 1957. LG.

- South African Pan-Africanist defiance of pass laws, 1960. LG.

- International boycotts and embargoes on South African products, from 1960. LG.

H. Against New Attempts to Impose Undemocratic Rule

(Many of these actions were in support of the legitimate regime.)

- Kanara (India) non-cooperation, 1799-1800. LG.

- German workers’ general strike vs. the Kapp putsch, March 1920. LG.

- Ruhr passive resistance vs. French and Belgian occupation, 1923. LG.

- Major aspects of the Dutch resistance, 1940-5, including several important strikes. MX.

- Major aspects of the Danish resistance, 1940-5, including the Copenhagen general strike, 1944. MX.

- Major aspects of the Norwegian resistance, 1940-5. MX.

- General strike in Haiti vs. Provisional President Pierre-Louis, 1957. LG.

- British and UN economic sanctions vs. Rhodesia, from 1965. LG.

The very considerable differences among these struggles, in the types of issues, the groups involved, the countries, cultural and historical backgrounds, etc., should be noted. Although the list is neither complete nor representative, a few very tentative conclusions can be drawn which suggest that some widely-held views about the technique of nonviolent action may be inaccurate.

Forty-eight of these cases took place in the “West” (including Russia); twenty-three in the “East”; nine in Africa; and one in Australasia. (See, for example, The Strategy of Civilian Defence: Non-violent Resistance to Aggression, edited by Adam Roberts, London: Faber and Faber, 1967) Three of these cases were international. Something less than forty per cent took place in “democracies” (roughly defined), and slightly more than sixty per cent under “dictatorships” (including foreign occupations) and seven cases under totalitarian systems. In some of these cases the nonviolent actionists partly or fully succeeded in achieving the desired objectives; and in other cases—for example, many of the anti-war actions—they failed. In not more than nine of these eighty-four cases were both the leadership and the participants pacifist.

Even making allowances for an incomplete and unrepresentative list, these figures are sufficient to challenge the conception that nonviolent action is mainly an “Eastern” phenomenon, that it is only applied under “democratic” conditions, that it is suitable only for convinced pacifists, and that it ignores the existence of conflicts and power.

Learning From the Past

Generally speaking, very little effort has been made to learn from past cases of nonviolent action with a view to increasing our understanding of the nature of the technique, and gaining knowledge useful in future struggles, or which might contribute to an expansion of the use of nonviolent action instead of violence. Study of past cases could provide the basis for a more informed assessment of the future political potentialities of the technique.

There are far too few detailed documentary accounts of past uses of nonviolent action; such accounts can provide raw material for analyses of particular facets of the technique and help in the formulation of hypotheses, which might be tested in other situations. An important step, therefore, in the development of research in this field is the preparation of purely factual accounts of a large number of specific cases of nonviolent action, accompanied if possible with collections of existing interpretations and explanations of the events.

A compilation, more extensive than the preliminary listing above, of as many instances of socially or politically significant nonviolent action as can be discovered is also needed, and should preferably include a few standard major facts about the cases, and bibliographic clues. Such a survey could help in the selection of the cases meriting more detailed investigation; and it would make possible more authoritative comparisons of the cases with particular factors in mind, such as the geographical, historical, and cultural distribution of the cases, the types of issues involved, and the types of opponents against whom nonviolent struggles have been waged.

Another subject which deserves careful study is the meaning of, and conditions for, success in nonviolent action. The varying meanings of the terms “success” and “defeat” need to be distinguished, and consideration given to concrete achievements in particular struggles. The matter is much more complex than may at first appear. For example, failure within a short period of time to get an invader to withdraw fully from an occupied country may nevertheless be accompanied by the frustration of several of the invader’s objectives, the maintenance of a considerable degree of autonomy within the “conquered” country, and the furtherance of a variety of changes in the invader’s own regime and homeland; these changes may themselves later lead either to the desired full withdrawal, or to further relaxation of occupation rule. When various types of “success” and “defeat” have been distinguished, it would be desirable to have a study of the conditions under which they have occurred in the past and seem possible in the future. These conditions would include factors in the social and political situation, the nature of the issues in the conflict, the type of opponent and his repression, the type of group using nonviolent action, the type of nonviolent action used, taking into account quality, extent, strategy, tactics, methods, persistence in face of repression, etc., and lastly the possible role and influence of “third parties”.

The question of the viability and political practicality of the technique of nonviolent action is one that can be investigated by research and analysis, and it is possible that the efficiency and political potentialities of this technique can be increased by deliberate efforts. The question of violent or nonviolent means in politics and defense, if tackled in this manner, is removed from the sphere of “belief” or “non-belief” and opened up for investigation and research.

Reference: IISG/WRI Archive Box 402: Folder 1. We are grateful to WRI/London and their director Christine Schweitzer for their cooperation in our WRI project.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Gene Sharp (b. 1928) is one of the world’s leading experts on the history, theory, and practice of nonviolence. His three-volume work The Politics of Nonviolent Action (Boston: Porter Sargent, 1973) is considered essential reading for anyone interested in any aspect of nonviolence and nonviolent struggle. He is Professor Emeritus of political science at the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth and was for thirty years a research fellow at Harvard’s Center for International Affairs. He is also founder of the Albert Einstein Institution in Boston, a non-profit organization concerned with nonviolent action and conflicts.