Some Thoughts on Darwin, Gandhi, and Einstein

by B.D. Nageswara Rao

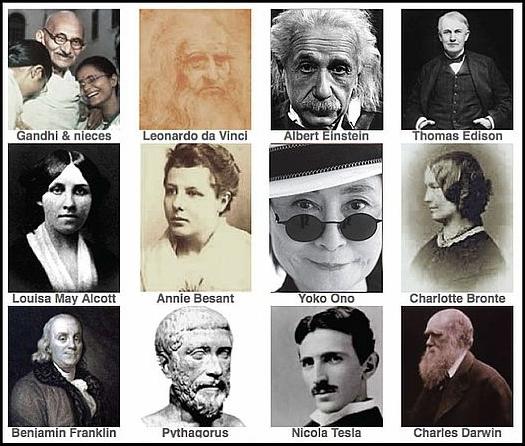

“Famous Vegetarians”; artist unknown; courtesy of herenow4you.net

Abstract

Gandhi’s message of nonviolence, and the methods he devised to practice it, are widely acclaimed to be of historical significance. However, his altruism seems contrary to the central tenet of Darwinism that survival is optimized for those who are adapted to the environment, i.e. those who are best prepared for war have the best chance of survival in a world where disputes are settled through violence. Nevertheless he chose nonviolence as an inviolable constraint in addressing all types of human problems and proclaimed, “While there are causes for which I am prepared to die, there is no cause for which I am prepared to kill.” His formulations of Salt Satyagraha, civil disobedience and non-cooperation movements are striking examples of profound analytical thought analogous (in my view) to Einstein’s formulation of the Special Theory of Relativity. Einstein was confronted with the experimentally proven fact that the velocity of light in vacuum is unchanged in a moving frame of reference. With this inviolable constraint he reformulated the laws of Newtonian mechanics by invoking a previously unthinkable requirement that mass, length and time change in a moving frame of reference, and thereby deduced the principle of mass-energy equivalence (E=mc2). Thus the Special Theory of Relativity was born, and a new era emerged in physics. Gandhi’s principle of nonviolence offered an alternative to war in solving global disputes, and thus ushered in a new era in human history. His message has influenced other reformers around the world, notably Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela. That it is not widely embraced is an indication of the fact that, functionally, human beings are basically driven by primitive Darwinian pressures generated by the reptilian brain, and have not allowed themselves to be persuaded adequately by the capabilities of the human brain which gave rise to ethics, altruism, and egalitarianism in our societies.

I am not an expert on Darwin or Gandhi and although I am a physicist by training, I do not specialize in relativity so that I am not an expert in Einstein either. However, in thinking about Gandhi’s message of nonviolence, I looked at it from the point of view of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution, and that raises some questions in my mind, and in my efforts to understand the methods he devised to organize nonviolent movements I saw intellectual parallels to Einstein’s development of the Special Theory of Relativity. I briefly stated these points in the abstract. I will elaborate on these now.

One of the central tenets of Darwin’s Theory of Evolution, which is commonly referred to as “survival of the fittest”, says that the chances of survival are optimized for those who are best adapted to their environment. In this statement, survival includes the ability to find food to live by, protection from predators and the ability to raise one’s progeny. Environment implies not only the atmospheric conditions, but also the ability to ward off danger and protect oneself and one’s progeny from predators.

When this idea of “survival of the fittest” is considered in the context of human beings, a number of the factors in the paradigm need to be redefined or modified. This is primarily due to the fact that human beings have developed abilities to control their physical environment, and human beings have no predators among the other animals. That is to say, the only predators for human beings are other human beings, as I will explain now. This vast power and control of the environment that human beings have achieved is, in turn, due to their development of their brains, and of their ability to communicate with each other in great detail in written languages so that they can share their brain power (such as in the development of science and technology).

However, humans do not necessarily all work together as one group for their collective and common good. They distinguish each other on the basis of geographic, religious and racial divisions. Since there are no predators for humans, when we say “fittest”, we effectively refer to those groups which garner a larger share and control of nature’s resources such as land, oil, metals, and minerals. Thus as different groups (such as national, racial and religious groups) compete for these resources, disputes between these groups inevitably follow. The various groups of human beings then use the same brainpower that enabled them to control the world’s resources and environment, to develop vast and elaborate military machinery to conduct war. Human beings thus became their own predators, and those who are most adept and well equipped to make war have become the fittest or the strongest. Their survival was, therefore, optimized in the Darwinian sense.

Gandhi grew up in colonial India, studied law in England (his scholastic abilities were quite unremarkable) and went to South Africa to practice law. There he was exposed to racial discrimination. He decided to fight against this discrimination as a citizen member of the British Empire, mind you, and not against colonialism. In organizing these protests he completely eschewed violence and was able to get a number of people to follow his message. He was quite successful in demonstrating that a nonviolent approach can yield results if it is tailored to appeal to the conscience and wisdom of the oppressor after getting his attention through protest. The goals of his protest movements were, nevertheless, limited to achieving certain rights and privileges and eliminating or minimizing the effects of certain discriminatory practices against the Indian community. Such peaceful protest movements involving relatively small groups of people also happened in different parts of the world in the past. In this sense, his activities in South Africa are not unique, although it appears in retrospect that it was here that he realized the profound significance of nonviolence as a “principle” for humanity as a whole.

After his return to India, Gandhi became immersed in India’s quest for freedom from the British. However, he made the personal choice of making his participation subject to the “inviolable constraint” of nonviolence. He proclaimed that, “while there are causes for which I am prepared to die, there is no cause for which I am prepared to kill.” This statement is contrary to the Darwinian paradigm of “survival of the fittest”. In a contest between a practitioner of violence and one practicing violent war, the survival of the nonviolent individual is guaranteed to fail. However, for Gandhi there was no question of compromise on this. This was a dispute in which 300 million citizens of the subcontinent wanted to achieve freedom from what was then the most powerful military power on earth without spilling any blood. Such an attempt was without precedent in human history. There were examples of kings like Ashoka, under the influence of Buddha, wanting to renounce war. There were many groups of people who practiced nonviolence at a personal level such as the Jains wearing masks to avoid destroying small insects or even bacteria when they breathe, Buddhists digging the ground gently to see that none of the worms get destroyed in the process, and saintly individuals eschewing all forms of personal violence in their lives. However, in collective disputes involving millions of people, and large chunks of nature’s resources such as land and oil, the modus operandi of nonviolence was not known. But since nonviolence was an inviolable constraint for Gandhi, he had to discover and devise methods to wage a war (so to speak) not only without resorting to violence, but also without the driving force of hatred of the enemy. It had to be profoundly original.

It was while contemplating what Gandhi’s thought processes might have been, that I discovered a striking parallel between his predicament and that of Albert Einstein before he discovered the Special Theory of Relativity. Einstein was confronted with the experimentally proven fact that the velocity of light in a vacuum is unchanged in a moving frame of reference. Since light is required for all observations, this invariance of its velocity had to be an “inviolable constraint” in the formulation of the laws of mechanics. Such a constraint was without precedent, and Einstein had to think entirely out of the box. He reformulated the laws of Newtonian mechanics by invoking a previously unthinkable requirement that mass, length and time change in a moving frame reference. Once this idea is invoked a number of experimentally testable hypotheses follow, including the famous principle of mass-energy equivalence (E=mc2). Thus, the Special Theory of Relativity was born and a new era emerged in physics. As a parallel, Gandhi confronted the problem of the British colonizing India and wanted to bring it to a close with the “inviolable constraint” of nonviolence. He had to devise ideas and methods that had not been thought of or practiced earlier. However, the parallel ends here.

Einstein’s goals were achieved through the analytical power of mathematical relationships and his explanations and hypotheses were tested by the validating power of experiments. Gandhi, on the other hand, had to think of methods not practiced before, and had no means to determine ahead of time whether they would work. In fact, the idea of accomplishing the mammoth problem of freeing India with some passive, and seemingly inactive, actions that nonviolence connotes, seemed laughable and doomed to fail, to many including Nehru. However, Gandhi had unshakable faith in the moral power of his approach and believed that passive resistance (Satyagraha) is, in fact, an active and powerful form of protest. Gandhi recognized two important factors in his plan: to galvanize a large number of people to his cause and to provoke a response from the British. However, these goals should be reached with no component of hatred or threat to the enemy. If one were to consider this problem of how to organize such a movement, as an academic exercise in strategy development, one would be left clueless as to what needed to be done. Viewed from this perspective, Gandhi’s development of “Satyagraha”, in particular “Salt Satyagraha” (see below) in the context of achieving the dual purpose of rallying and galvanizing millions of his countrymen, and of provoking a response by rattling the conscience of the British, was a striking example of deep and original thought. It has elements parallel to a military strategy in the matter of paying meticulous attention to detail and sense of purpose. Personally, when I tried to analyze his methods in this manner, I was simply astonished by the genius of Gandhi in addressing an extraordinarily complex problem. I am not advocating here that the brilliance of thought and strategy has anything to do with the principle of nonviolence. On the other hand, human history is replete with examples where such brilliance is pointed out and admired in the pursuit of victories in violent war. Achieving success through nonviolence requires nothing less in quality and commitment. More significantly, in the end there is no victor and vanquished, but peace and harmony.

Gandhi was in jail for several years before the events of “Salt Satyagraha”. Whenever he was imprisoned, he welcomed it as an opportunity to think, reflect and rejuvenate his mind. (He had no property, so the British could not deprive him of anything. It is frustrating to a tyrant if the subject seems to enjoy the punishment given.) There he formulated Salt Satyagraha. Of all the laws that the colonizers made to oppress, he chose to oppose the salt tax; people had to pay a tax if they made salt and sold it. Why did he choose salt? Perhaps because all the peasants understood salt; it was a staple of their diet, and in such a hot climate even a necessity. The population of India was largely illiterate and poor. They could not follow the intricate logic of pamphlets or cogently organized speeches or get excited or agitated about the effects of laws like the “Succession Act” (this was one of the causes for the 1857 Sepoy mutiny against the British). He simply said to the British, “This is our land. We make salt out of seawater and use it for our food every day. You come from England, occupy our land, and tell us that we cannot collect seawater, dry it out, eat salt from it, without paying you some money. We will make our own salt. We refuse to pay you this tax.”

Gandhi started the Salt Satyagraha march with five people leaving Sabarmathi Ashram one fine morning. He informed the Governor General, Lord Irwin, that he would do this. He walked nearly 250 miles for over three weeks to the seashore where salt was planned to be made. The crowd swelled to many thousands and parallel treks took place all over the country along its long shoreline. Photographers and newsmen came in from around the world and newspapers in the west were filled with reports and pictures day after day. The world waited for this frail man walking with a staff in his hand vigorously leading an army of ordinary unarmed citizens walking to the beaches where they had grown up and played, to make some salt for their food. The nation rallied, the government was provoked. The powerful British could not quash the movement without looking hopelessly silly in front of the rest of the world, shooting at peasants making salt. So they arrested them, until some jails were full to overflowing. They even arrested the aged mothers of some of the leaders like Nehru.

In fact, it took 15 more years after this for India to win freedom. The country was partitioned. Hindus and Muslims slaughtered each other by the millions. Gandhi’s mission failed, in effect, to save many Indian lives. The lives that were spared were those of the British. But the point was made for the whole world. The British were shaken and chastised by the moral power of this frail man. This was a turning point. Gandhi’s method and message offered an alternative to war in which, perhaps, humanity can perceive greater glory not in the mindless and maniacal destruction in the name of solving disputes, but by the use of human intelligence in building harmony across the globe and solving disputes without the use of violence.

Let us return to Gandhi’s message of nonviolence in the context of the theory of human evolution. As stated earlier, the only predators of human beings are other human beings, and most of their disputes are normally settled through violence. If nonviolence is adopted, it will end the need for one group of humans to plan the extinction or subjugation of another. Since the disputes owe their origin primarily to garnering a lion’s share of the resources of the planet, the nonviolent alternative leads to a more equitable distribution of the world’s resources. Gandhi said, “There is enough in this world for everyone’s need, but there is not enough for everyone’s greed.” With the nonviolent alternative, the limits on resources are likely to be more uniformly recognized so that conservation becomes common; wastage will be discouraged more naturally. Gandhi used to call such waste “violence against nature”. Thus, viewed in a broad perspective, Gandhi’s message of active nonviolence has global implications far beyond the simple practice of not resorting to violence. That said, it must be recognized, however, that Gandhi’s active nonviolence is, as I see it, exceedingly difficult to practice. Firstly, for ordinary people living through the pressures of day-to-day struggles in modern life, it leads to significant levels of personal discomfort and inconvenience to say the least, and more often it leads to physical hardship that is not easy to endure. Even if one wants to be serious about it, there is no magic formula as to how to apply an active form of nonviolence to every situation where some kind of societal protest is warranted. It is, in this sense, intellectually most demanding. Finally, and this is the most important, the life of a practitioner of nonviolence is highly vulnerable. If you over-provoke the violent oppressor he might kill you; and if you reach out to the perceived enemy and curb too much your own people from taking to violence, they might even kill you. Gandhi was assassinated by a Hindu zealot. Martin Luther King Jr., the most renowned follower of Gandhi’s message of nonviolence, was also assassinated. So was Yitzhak Rabin when he sought peace.

Such events make you stop and think about whether Gandhi’s message has any future. Let us first recognize that nonviolence is relevant only in the human context. For the lower animals there is a food chain, an organized Darwinian ladder in which stronger animals live off the weaker ones. (They do not, however, ordinarily destroy their own kind.) Darwinism in that sense, does not optimize the survival of the altruistic or noble hearted, it optimizes the survival of those that are best adapted to their environment even if they are vicious and mean.

However, there is reason for hope. Humans, perhaps with the comfort of knowing they control their world, and through the development of their brains, have evolved new concepts outside the aforementioned tenets of Darwinism, such as ethics, fairness, and egalitarianism. They have developed laws, courts, apparatus for protection of social order, and institutions such as the United Nations to minimize global violence. So a beginning was made. The very fact that people like Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. were able to function and achieve laudable social objectives gives us room for optimism. So while we are capable of blowing each other up, we are also capable of a lot of good. A friend recently said to me in a mood of despondency about the state of the world, “the world needs another Gandhi now”. That is not likely to happen. Gandhi was a rare individual; people like him appear once in a great while. Mountbatten compared him to Jesus Christ and Buddha. Einstein wrote that generations to come would “scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth”.

Gandhi is gone. But his message lives on forever. It has universal value, provided human beings know how to adapt it in their interactions. His message strongly influenced other thinkers and social reformers around the world, notably Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela. In recent times there have been a large number of liberation and protest movements in the Middle East and Africa, among others, which were primarily nonviolent. (Many are documented by George Lakey’s Global Nonviolent Action Database, a website managed by Swarthmore College, and the website wagingnonviolence.org.) Some of the organizers of these activities seem to view it as a fruitful tactic, rather than as a principle in the manner of Gandhi and Martin Luther King. Irrespective of the moral strength of commitment to the principle of nonviolence, the fact that it is adapted is most gratifying. That it is not widely embraced is an indication that, functionally, human beings are still primarily driven by Darwinian pressures generated by the reptilian brain, and have not allowed themselves to be persuaded adequately by the capabilities of those parts of the human brain (the neo-cortex) that gave rise to ethics, altruism and egalitarianism in our societies. Let us hope that as the future unfolds our evolution will be guided by this part of the neo-cortex, so that Gandhi’s message will not be in vain.

EDITOR’S NOTE: B.D. Nageswara Rao is Professor of Physics, Indiana University Purdue University. His research program, as stated on the university’s website, “is in the general area of application of magnetic resonance techniques (NMR & EPR) to the study of structure-function relationships in biological macromolecules.” Among his awards are Research Fellowship of the Muscular Dystrophy Association of America; Glenn W. Irwin Jr., M.D., Research Scholar Award for Unique and Significant Contributions to Research, and Fellow of the American Physical Society. Please click on this link for a list of his publications and further biographical information.

This essay is based on a talk presented at the 17th Vedanta Congress September 19-22, 2007. A condensed version was also published in Bhavan’s Journal, Vol. 58, No 10, December 31, 2011, pp 41-50.