Gandhi’s Art: Using Non-Violence to Transform “Evil”

by William J. Jackson

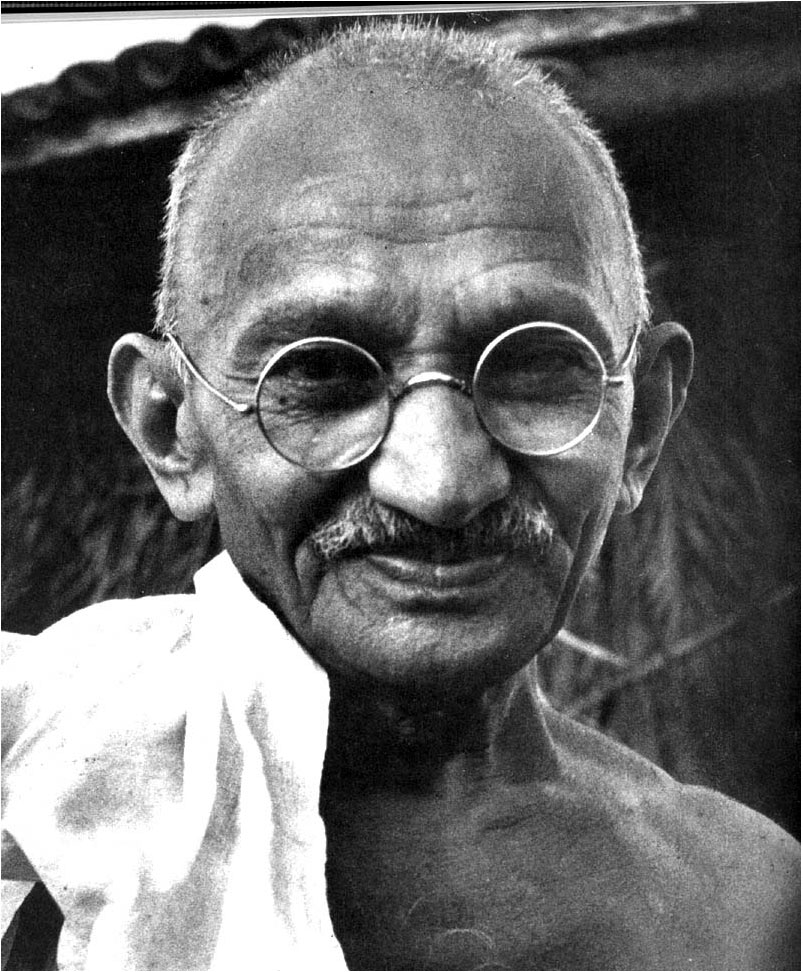

Gandhi c. 1945; photographer unknown;

a public domain image,

courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“Changing the world begins with changing yourself; you have to become the change you want to see in the world.” M. Gandhi

The most Gandhi-like person I know is a very patient and gentle yogi who lives in New Delhi. When I wrote to him to say that I was preparing this article, he replied, “Making an honest and sincere attempt to practice exactly what one preaches is not easy—but Gandhiji did it to near perfection; at the cost of enormous physical as well as mental hardship, he examined his life in light of his convictions with brutal honesty, and underwent enormous inner suffering whenever he found himself wanting. That can give much greater torture than giving up physical comforts voluntarily, in which he also went to an extreme.”

Why was Gandhi so scrupulous? He himself said: “You have to become the change you want to see in the world.” Gandhi said that he thought Leo Tolstoy was the embodiment of truth in the age in which they lived: “Tolstoy’s greatest contribution to life lies, in my opinion, in his even attempting to reduce to practice his professions without counting the cost.” Gandhi said that reading Tolstoy’s writing “The Kingdom of God is Within You” changed his life, turning him from a votary of violence to an exponent of non-violence. Like Martin Luther King Jr., whom he inspired in turn, Gandhi always seemed ready to put comfort aside and to put his life on the line, without counting the cost. For example, when a leper came to his door in South Africa, Gandhi fed him, offered him shelter, dressed his wounds, and looked after him.