The Effectiveness of Non-Violent Struggle

by Bart de Ligt

We would do well to situate in an historical context not only this far-ranging essay by the Dutch anarcho-pacifist Bart de Ligt (1883-1938) but Gandhi’s writings as well. It is easy to lose sight of the international foment at the time of Gandhi’s nonviolent campaigns in South Africa and India, and to disregard the intensity of the contemporary discourse on peace and war in Europe and the United States. By the mid 1930s when de Ligt published this essay in his book The Conquest of Violence, a devastating World War I had ended only a few years before; the rise of Nazism alarmingly threatened the outbreak of another. The debate over militarism versus Gandhian nonviolence has here the air of a struggle for survival and informs de Ligt’s essay with a sense of passion and urgency. It goes a long way to explain why he is so comprehensive in mentioning the views of thinkers whose philosophies were compatible with aspects of nonviolent resistance. The nonviolent boycott and labor strike were well-established methods that might be used in the service of peace. De Ligt knew that Gandhi did not conceive of Satyagraha in a vacuum, nor was it ever isolated on some higher plane from contemporary life. Satyagraha was ever at the heart of historical engagement, a life force that might be marshaled against the force of war.

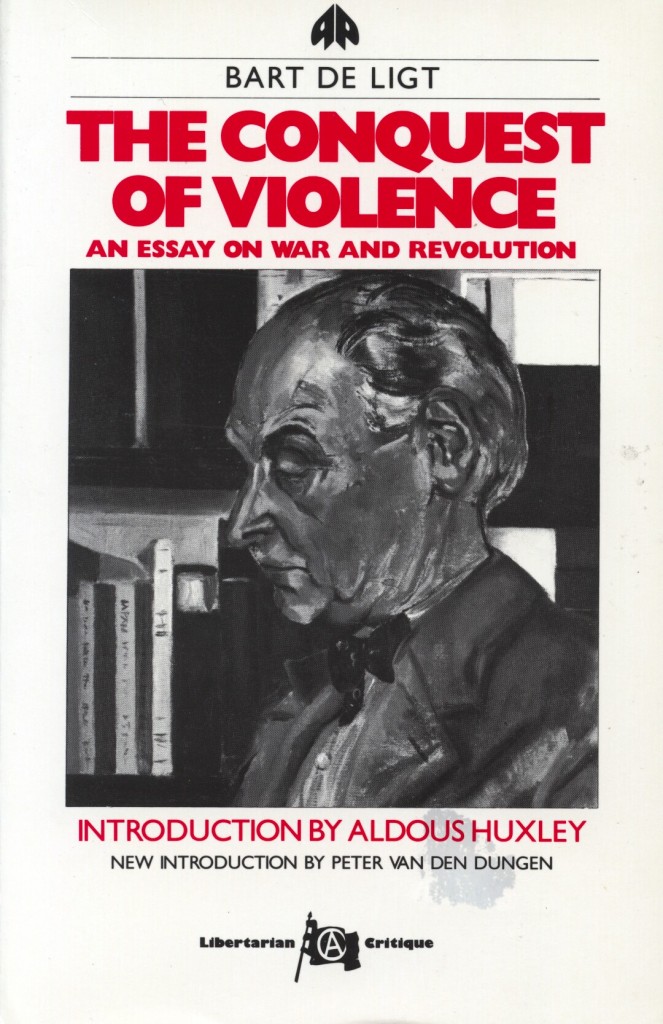

Pluto Press edition; illustration by Ingrid van Peski-de Ligt; courtesy of J. E. de Ligt.

Concerning his Satyagraha campaign in South Africa, Mohandas Gandhi wrote, “Non-violence is the law of our species as violence is the law of the brute. The spirit lies dormant in the brute and he knows no law but that of physical might. The dignity of man requires obedience to a higher law—to the strength of the spirit.”

How much more noble non-violent methods of struggle are than violent, and how much more effective, when they are well prepared!

Despite the justice of its cause, the religious fanaticism of its people, its famous marksmen, and a strategic geographical position the Transvaal was unable to hold out against the brutality of British imperialism. In the Transvaal in the early 1900s there lived a group of Hindu immigrants subject to harsh and special laws, which shackled them socially and economically and were profoundly offensive to their human dignity. Indian coolies were employed in the mines of Natal and elsewhere in South Africa, and they were tied to their work by five-year contracts. As a rule, they were very industrious. A great number of Indians, once their contracts had expired, stayed behind in the country as small farmers or tradesmen. By 1900 there were 12,500 Indians in the Transvaal. Although they had occupied the country by violence, the white people began to look on these peaceable rivals as undesirable intruders.