Nonviolent Founding Myths of the United States

by Benjamin Naimark-Rowse

On the Fourth of July, cities and towns from coast-to-coast across the United States host fireworks, concerts, and parades to celebrate our independence from Britain. Those celebrations will invariably highlight the colonial soldiers who overcame the British. But the lessons we learn of a democracy forged in the crucible of revolutionary war tends to ignore how a decade of nonviolent resistance before the shot-heard-round-the-world (1) shaped the founding of the United States, strengthened our sense of political identity, and laid the foundation of our democracy.

We are educated to believe that we won our independence from Britain through bloody battles. We recite poetry about the midnight ride of Paul Revere that warned of a British attack. (2) And we’re shown depictions of Minutemen in battle with Redcoats in Lexington and Concord.

I grew up in Boston where our veneration for Revolutionary battles against the British extends far beyond the Fourth of July. We celebrate Patriots’ Day to commemorate the anniversary of the first battles of the Revolution, and Evacuation Day to commemorate the day British troops finally fled Boston. And at the start of every Boston Red Sox baseball game we stand, take off our hats and (33,000 strong!) sing, in our national anthem, about the “perilous fight”, the “rockets’ red glare”, and the “bombs bursting in air that gave proof through the night that our flag was still there.”

Yet, founding father John Adams wrote that, “A history of military operations … is not a history of the American Revolution.” (3) In fact, American revolutionaries led not one, but three nonviolent resistance campaigns in the decade before the Revolutionary War. They helped to politicize early American society. And they allowed colonists to replace colonial political institutions with parallel institutions of self-government that helped form the foundation of the democracy that we rely on today.

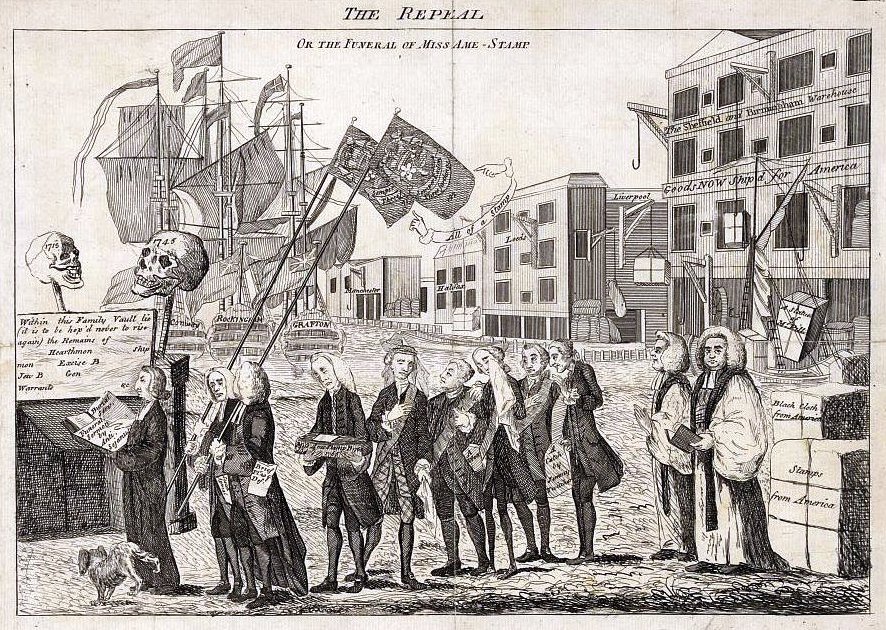

The first of these nonviolent resistance campaigns was against the Stamp Act of 1765. Tens of thousands of our forbearers refused to pay the British king a tax to print legal documents and newspapers, by collectively deciding to halt consumption of British goods. The ports of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia signed pacts against importing British products; women made homespun yarn to replace British cloth; and eligible spinsters in Rhode Island refused to accept addresses from any man who supported the Stamp Act.

Colonists organized the Stamp Act Congress, held in New York in October 1765. In a united front the Congress issued statements and broadsides about colonial rights and limits on British authority, and sent copies to every colony as well as one copy to the British parliament. This mass political mobilization and economic boycott meant the Stamp Act would cost the British more money than it was worth to enforce, leaving it dead on arrival. This victory also demonstrated the power of nonviolent non-cooperation: people-powered defiance of unjust social, political or economic authority.

The second nonviolent resistance campaign was against the Townshend Acts of 1767. (4) These acts taxed paper, glass, tea and other commodities imported from Britain. When the Townshend Acts went into effect, merchants in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia stopped importing British goods. They declared that those continuing to trade with the British should be labeled “enemies of their country.” A sense of a new political identity detached from Britain was growing across the colonies.

By 1770, colonists had developed the Committees of Correspondence, shadow governments organized by the Patriot leaders of the Thirteen Colonies on the eve of the American Revolution that constituted a new political institution detached from British authority. (5) The committees allowed colonists to share information and coordinate their opposition. The British Parliament reacted by doubling down and taxing tea, which led enraged members of the Sons of Liberty to carry out the famous Boston Tea Party. (6)

The British Parliament countered with the Coercive Acts of 1774, which effectively cloistered Massachusetts. The port of Boston was closed until the British East India Company was repaid for their Tea Party losses. Freedom of assembly was limited, and court trials were removed from Massachusetts.

In defiance of the British clampdown, colonists organized the First Continental Congress. (7) Not only did they articulate their grievances, the colonists also created provincial congresses to enforce the rights they had declared for themselves. A newspaper at the time reported that these parallel legal institutions effectively took government out of the hands of British-appointed authorities and placed it in the hands of the colonists, so much so that some scholars now assert that, “independence in many of the colonies had essentially been achieved prior to the commencement of military hostilities in Lexington and Concord.” (8)

King George III felt that this level of political organization had gone too far, noting that, “The New England governments are in a state of rebellion; blows must decide whether they are to be subject to this country or independent.” In response, colonists organized the Second Continental Congress, and appointed George Washington commanding general of the Continental Army. Thus began eight years of armed conflict. (9)

The Revolutionary War may have physically decided independence, but the subsequent focus on the war obscures the contributions that nonviolent resistance made to the founding of the country. During the decade leading up to the war, colonists articulated and debated political decisions in public assemblies. In so doing, they politicized society and strengthened their sense of a new political identity free from Britain. They legislated policy, enforced rights, and even collected taxes. In so doing, they practiced self-governance before a state of war ensued. And they experienced the power of nonviolent political action across the broad stretches of the land that was to become a nation.

On US Independence Day, let us celebrate our forefathers’ and mothers’ nonviolent resistance to colonial rule. And every day, as we deliberate the myriad challenges facing our democracy, let us draw on our nonviolent history just as John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, Patrick Henry, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington did over two hundred and forty years ago.

Endnotes: (JG)

(1) The phrase, “the shot heard round the world,” is from the opening stanza of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Concord Hymn” (1837). It refers to the opening salvo of the American Revolutionary War. According to Emerson’s poem, the fatal shot was taken on the North Bridge in Concord, Massachusetts, where the first British soldiers fell in the battles of Lexington and Concord.

(2) “Paul Revere’s Ride” (1860) is a poem by American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. It commemorates the actions of American patriot Paul Revere on April 18, 1775, although with significant historical inaccuracies. In the poem, Revere tells a friend to prepare signal lanterns in the Old North Church in Boston to inform him if the British will attack by land or sea,“One if by land, two if by sea.” Revere was to await the signal across the river in Charlestown and be ready to spread the alarm by horseback throughout Middlesex County, Massachusetts. The unnamed friend climbs up the steeple and gives the two by sea lantern signal. Revere’s ride through Medford, Lexington, and Concord to warn the patriots is what Longfellow commemorates, if with considerable poetic license. Wikipedia’s article on Paul Revere is a good place to start for a factual account.

(3) John Adams (1735 – 1826) was the second President of the United States, and its first Vice President. He was a delegate from Massachusetts to the Continental Congress, where he played a pivotal role in persuading Congress to declare independence. He assisted Thomas Jefferson in drafting the “Declaration of Independence” in 1776, and was its foremost advocate in the Congress.

(4) The Townshend Acts were a series of British laws passed in London, beginning in 1767, relating specifically to the British American colonies in North America. The acts are named after Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, who drafted and proposed the Acts.

(5) Some 7,000 to 8,000 Patriots served on these committees at the colonial and local levels. They comprised most of the leadership in the thirteen original colonies, but excluded anyone loyal to the British crown.

(6) The Sons of Liberty were a secret society formed to protect the rights of the colonists and to fight taxation by the British government. Besides the Boston Tea Party the society also played a major role in battling the Stamp Act, and the group officially disbanded after the Stamp Act was repealed.

(7) The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates from twelve of the Thirteen Colonies that met September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

(8) See especially, Walter H. Conser, Jr., Ronald M. McCarthy, David J. Toscano, and Gene Sharp, eds, Resistance, Politics, and the American Struggle for Independence: 1765-1775, Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1986.

(9) The Second Continental Congress was a convention of delegates from the thirteen colonies. It held its first meeting in the spring of 1775, in Philadelphia.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Benjamin Naimark-Rowse is a Truman National Security Fellow, and teaches and studies nonviolent resistance at The Fletcher School at Tufts University. The article has been shared with politicalviolenceataglance.org, and wagingnonviolence.org under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License agreement.