Glenn Smiley: Nonviolent Role Model

by Ken Butigan

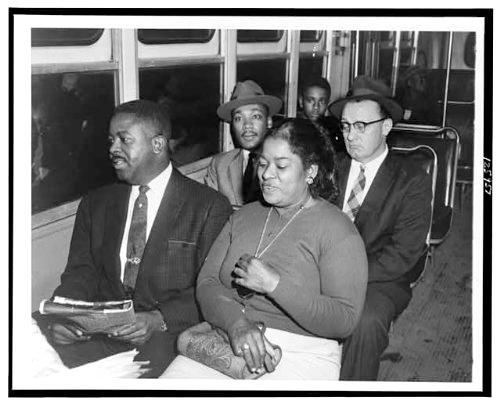

Ralph Abernathy, Martin Luther King, Smiley and unidentified woman, 1956 Bus Boycott; courtesy wagingnonviolence.org

During a visit years ago to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, I spent a lot of time at an exhibit where you could track the heredity of rock bands. Monitors displayed a family tree detailing what groups had influenced which bands. You could trace how particular acts had inherited, adapted or transformed genres, styles and musical innovations. For example, the Rolling Stones, to the best of my foggy recollection, were influenced by Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson, and Buddy Holly, as well as by Roy Orbison and the Kingston Trio. If even one of those ancestors was out of the mix, the Stones might have sounded very different — or maybe wouldn’t have formed in the first place.

If this kind of app existed for the world of nonviolent change, it would probably be less a tree than a kind of mind map, with many movements and persons influencing one another. It would feature numerous campaigns and certain pivotal pioneers. No doubt Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., Susan B. Anthony, Sojourner Truth and the Buddha would make an appearance. But a nonviolence family tree would go well beyond these recognizable figures. Like anything else, nonviolence has been imagined, constructed and tweaked over long periods of time by innumerable thinkers, and doers. A nonviolence genealogy would include the famous practitioners, but also many others whose contributions, sung or unsung, have made active nonviolence the creative force that it is.

One of these contributors is Glenn Smiley, whose life and work had a powerful impact on a series of social movements in the mid-20th century. Smiley died in 1993. Not long before that, I visited him in a cramped, nondescript office in Los Angeles where he was continuing the experiment in nonviolence that he began 50 years earlier.

I was in L.A. to meet and learn from a group of powerful women who were engaged in relentless, nonviolent action to end gang violence in their neighborhood. Their ongoing action — what they called “love walks” that grew into heartfelt encounters and then practical projects — laid the foundations for Homeboy Industries, an astonishing organization that today offers young people across the city employment opportunities, nonviolent options, healing and support. This would all come later, especially under the leadership of Rev. Greg Boyle. Back then, it was a small experiment in an alternative to passivity and violence.

Glenn Smiley was quite familiar with such experiments. In the 1940s he was profoundly influenced by War Without Violence (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1939) by Krishnalal Shridharani, which summarized Gandhi’s principles and methods of nonviolent change. A Methodist minister in Arizona and California for 14 years, Smiley learned that the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) were using Gandhian methods to challenge racial segregation and decided to join the struggle, including campaigns to desegregate tea rooms in L.A. As he later wrote, “Some of the classic illustrations of nonviolence grew out of Los Angeles and included the Bullock’s Tea Room project that lasted three months. It ended in a dramatic victory for what would now be called a sit-in, as the tea room was opened up to African-Americans.”

When World War II began, he refused to serve in the armed forces — and also refused the exemption that members of the clergy were granted. Like several thousand others, he was jailed during the war for conscientious objection.

When the Montgomery Bus Boycott started in 1955, long-time nonviolent activist Bayard Rustin, who worked for the War Resisters League, responded to Dr. King’s call for support by joining the struggle and helped him comprehensively explore the power of nonviolence. As Mary King wrote, “Plying him with books at night, he helped him to analyze Gandhi, and was the first tutor to teach King the essentials of nonviolent struggle systematically.”

Soon, the Fellowship of Reconciliation sent Smiley, who by then was the organization’s national field director, to also offer his support, and, like Rustin, to help Dr. King plumb the depths of the theory and method of nonviolent people power and to root the Montgomery movement firmly in these principles.

Smiley organized nonviolence training throughout the South beginning in 1956, and encouraged students to attend the conference at Shaw University where the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was formed.

Later he founded Justice-Action-Peace Latin America, a Methodist-inspired group that organized seminars on nonviolence in Latin American countries from 1967 through the early 1970s and, later still, a nonviolence center in Los Angeles.

In his late sixties Smiley suffered a series of strokes and was unable to speak for 15 years. Then one morning he woke up to find he had regained his speech — and went on to give 103 lectures in the two years before his death. He also resumed his work with the Fellowship of Reconciliation.

While there was some contention in the late 1950s about the extent of FOR and Smiley’s contribution to the adoption of nonviolence in the Montgomery campaign (at the time Dr. King wrote that Smiley’s “contribution in our overall struggle has been of inestimable value,” but also noted that he feared “that this impression has gotten out in many quarters because members of the staff of FOR have spread this idea”), there is little doubt that Smiley and Rustin helped consolidate the pivotal role of nonviolence in the movement.

With the success of the Montgomery boycott, the profile of nonviolence as a powerful and potentially successful means of struggle grew, spreading throughout the South and then throughout the world. It is now widely understood that the lessons and dynamics of the U.S. civil rights movement have had a global impact, disseminating the vision, principles and methods of active and liberating nonviolence.

If it has played this monumental role, we would do well to ponder the parts of the mind map that have contributed to it. In addition to the thousands of women, men and children who carried the movement forward with their spirit and their bodies from Montgomery to Little Rock, from Birmingham to Selma, there are those such as Glenn Smiley and Bayard Rustin who helped frame the direction of the movement — and whose contribution continues to resound in every action, campaign or movement across the planet that consciously or unconsciously draws from those seminal struggles.

Like the chord progression or guitar lick passing from one band to the next, we can still hear the bass line of social change worked out all those years ago that’s still there for us to adapt, improvise and improve on. This would, no doubt, bring a smile to Glenn Smiley’s face.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Ken Butigan is director of Pace e Bene, and teaches peace studies at DePaul University and Loyola University in Chicago. We have posted a number of his articles, accessible via the Author Archives link at the top of the page, or by clicking on his byline.