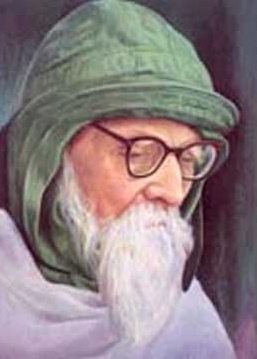

The King of Kindness: Vinoba Bhave and His Nonviolent Revolution

by Mark Shepard

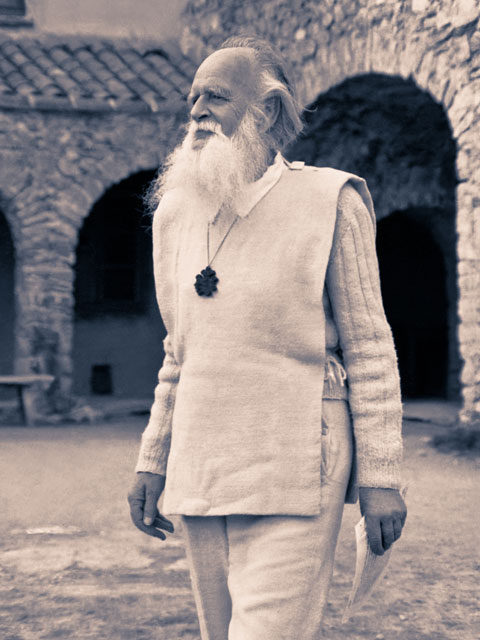

Once India gained its independence, that nation’s leaders did not take long to abandon Mahatma Gandhi’s principles. Nonviolence gave way to the use of India’s armed forces. Perhaps even worse, the new leaders discarded Gandhi’s vision of a decentralized society, a society based on autonomous, self-reliant villages. These leaders spurred a rush toward a strong central government and a Western-style industrial economy. But not all abandoned Gandhi’s vision. Many of his “constructive workers”, development experts and community organizers working in a host of agencies set up by Gandhi himself, resolved to continue his mission of transforming Indian society. And leading them was a disciple of Gandhi previously little known to the Indian public, yet eventually regarded as Gandhi’s “spiritual successor”, Vinoba Bhave, a saintly, reserved, austere man most called simply Vinoba. How did he assume this status?

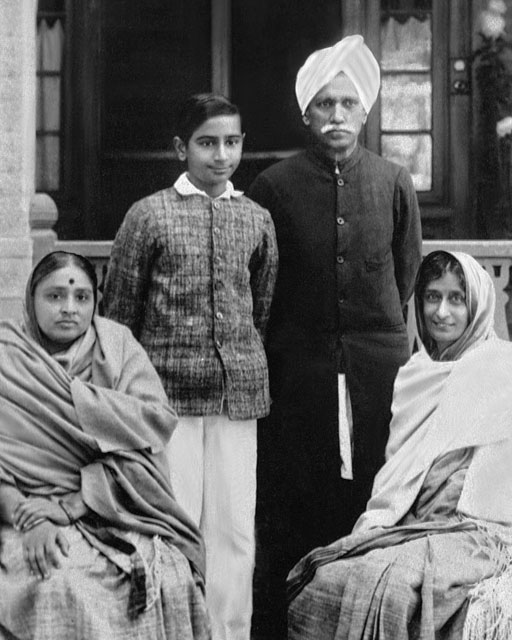

In 1916, at the age of 20, Vinoba was in the holy city of Benares trying to come to a decision about his life. Should he go to the Himalayas and become a religious hermit? Or should he go to West Bengal and join the guerillas fighting the British? Then Vinoba came across a newspaper account of a speech by Gandhi. He was thrilled, and soon after joined Gandhi in his ashram. Gandhi’s ashrams were not only religious communities, but also centers of political and social action. As Vinoba later said, he found in Gandhi the peace of the Himalayas united with the revolutionary fervor of Bengal.