Gandhi and Ecological Marxists: The Silent Valley Movement

by A. S. Sasikala

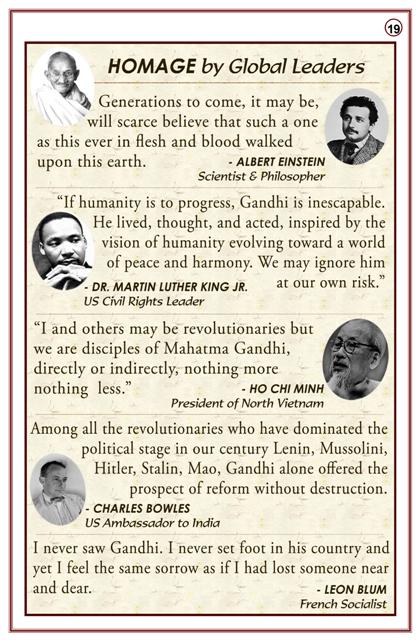

Environmental concerns were not much considered at the time of Gandhi, but his ideas on village decentralisation and national unity such as Swaraj, Swadeshi, Sarvodya, and especially the Constructive Programme makes him an advocate of environmentalism. He is generally considered to have had deep ecological views and his ideas have been widely used by different streams of environmentalism such as Green parties and the deep ecology movement founded by Arne Naess. The eminent environmental thinker Ramachandra Guha identified three distinct strands in Indian environmentalism, crusading Gandhians, ecological Marxists, and appropriate technologists, these last being advocates of small-scale, environmentally sound technology, most often known as “intermediate technology”. Guha observed that, unlike the third, the first two rely heavily on Gandhi, but Indian ecological Marxists also used Gandhian strategies and tactics. The Silent Valley Movement in Kerala, south India, is a case in point of just how ecological Marxists were willing to use Gandhian techniques in order to fight against environmental injustice. The role of the Marxist KSSP, Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad (translated as Kerala Science Literature Movement, and also referred to as Kerala People’s Science Movement, PSM) illustrates their various strategies. Methodologies adopted throughout the movement were inspired by Gandhian methods, as previously used by other environmental movements like Chipko [see Mark Shepard’s article here].