by Douglas Kerr

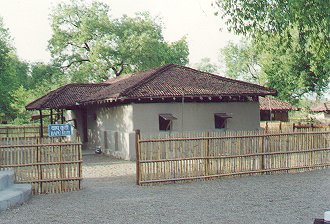

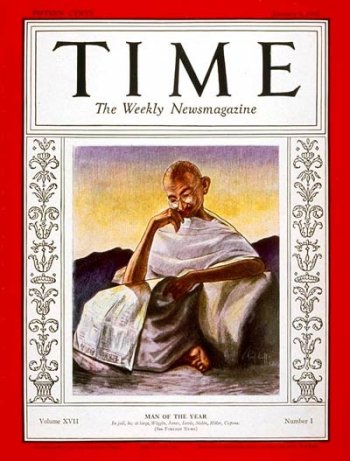

Ayad Burnat speaking to Israeli soldiers in Bil’in; courtesy ifpb.org

Interfaith Peace Builders Preface: Bil’in is a small, peaceful Palestinian village 7 miles west of Ramallah. It has continued its struggle to maintain its existence by fighting to protect its land, olive trees, resources, water and liberty. Its population of 1900 live in an area of approximately 1000 acres or 4000 dunams. The residents of Bil’in depend on agriculture as their main source of income, but close to 60% of Bil’in’s land has been annexed to build Israeli settlements and Israel’s Separation Barrier, destroying more than 1,000 olive trees in the process. Israel began construction of the illegal Separation Barrier in April 2004 by appropriating 570 acres (2300 dunams) of Bil’in land. Residents resisted these injustices despite the increase in night raids by the Israeli Defense Force (IDF), arrests and injuries of its residents and activists, and two fatalities. Indeed, Bil’in’s residents, joined by Israeli and international activists, have peacefully demonstrated every Friday in front of the Separation Barrier and the IDF have responded with both physical and psychological violence. Working side-by-side with international and Israeli activists, the people of Bil’in managed to achieve recognition by the Israeli Supreme Court in 2007, when it ruled that the route of the Separation Barrier was illegal and must be changed. The Israeli Defense Force, however, toughened its oppression by systematically arresting members of Bil’in’s Popular Committee, namely, those in charge of organizing the nonviolent demonstrations. In 2009, Abdullah Abu Ramah, coordinator of the Popular Committee Against the Wall in Bil’in, was arrested in his Ramallah home. Despite his recognition by the EU as a “human rights defender,” he was found guilty of “incitement” and “illegal protest,” and imprisoned for 16 months. In June of 2011, in accordance with the 2007 Israeli Supreme Court decision, the Separation Barrier was re-routed and 300 acres (1200 dunams) returned to the village. The Wall and settlement projects to date (2015) still occupy 270 acres (1100 dunams) of Bil’in land. Bil’in’s residents continue steadfastly to demonstrate each Friday. They are the subject of the film 5 Broken Cameras, the 2013 Academy Award Nominee for Best Documentary film, directed and narrated by Emad Burnat, brother of Ayad Burnat. R.H. Tracy

Douglas Kerr: How did the nonviolent popular resistance to the Occupation first start in Bil’in?

Ayad Burnat: It is now nine years, in December 2004, since we started nonviolent resistance, when the Israeli bulldozers started to destroy the land, the olive trees of the farmers. All of the people went outside, without prompting, to try to stop the bulldozers from destroying their land. Bil’in is a small village with a population of around 1900 and about 4000 dunams [c. 1000 acres] of land. The Israeli government confiscated 2,300 dunams. This land is full of olive trees. It is the life of the farmers in the village, and most of the people in the village are farmers. This land is their life. We started our nonviolent struggle in Bil’in when we saw these bulldozers destroying the olive trees, and we continued. Between December and February 2005, there was a demonstration every day.

Read the rest of this article »