Book Review: The Root of War Is Fear: Thomas Merton’s Advice to Peacemakers

by David M. Craig

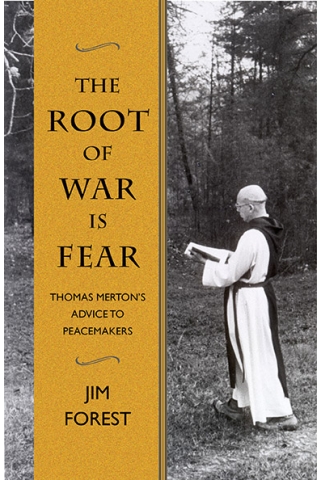

Dustwrapper art courtesy Orbis Books; orbisbooks.com

Jim Forest has written a deeply personal book, The Root of War Is Fear: Thomas Merton’s Advice to Peacemakers (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2016). It is personal in two ways. First, the book is a memoir of Forest’s encounters with Merton during the 1960s. A co-founder of the Catholic Peace Fellowship and former managing editor of The Catholic Worker, Forest stumbled upon Merton’s spiritual autobiography The Seven Storey Mountain in late 1959 when he was still in the United States Navy. Up until Merton’s untimely death in 1968, Forest corresponded with Merton and visited him at his Trappist monastery in Kentucky. The book’s chapters proceed chronologically, weaving substantial excerpts from Merton’s writings on peace and war into an assessment of his intellectual, moral, and spiritual significance for the Catholic Church, peace activists, and Forest himself.

Second, the book locates the beating heart of Merton’s transformative influence in a Christian personalism. This theology affirms that every person is God’s child, while revealing each person as woefully self-justifying yet still redeemed in Jesus Christ. Merton’s theology manifests in vivid flashes of writing, not abstract doctrinal statements like this one. For example, Merton decided to intervene more publicly in contemporary debates following his 1958 epiphany on a Louisville street corner. Merton recounts how the “illusory difference” of human separateness vanished in a rush of unbounded joy that “God Himself gloried in becoming a member of the human race.” He continues, “There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun… There are no strangers… If only we could see each other [as we really are] all the time. There would be no more war, no more hatred, no more cruelty, no more greed… I suppose the big problem is that we would fall down and worship each other.” (17-18, ellipses and brackets are Forest’s.)

For Merton, the more urgent problem is that human beings rarely see each other. People are dominated by the insistent legitimacy of their perceived needs, desires, and hopes. The inverse of this self-confirming myopia is a boundless fear of the other, generated, in Forest’s words, by “the human tendency to accuse the other rather than accuse oneself, so that, failing to recognize our own co-responsibility for evils that led to war, we come to see war—even nuclear war—as necessary and justified.” (28) When personal fears ignite the fires of nationalism, entire societies entrust their “security” to ideologies, technologies, and systems that led, in Merton’s day, to the nuclear brinksmanship of mutually-assured destruction. Forest joined Dorothy Day, editor and co-founder of The Catholic Worker, in sitting on Central Park benches during civil defense drills to dramatize the folly of this doctrine and the empty hopes of salvation in bomb shelters.

Forest organizes his exposition of Merton’s advice to peacemakers around several narratives. In one storyline, he argues that Merton’s writings helped disrupt the Catholic Church’s uncritical application of just war theory. In 1941 Merton’s claim to be a Catholic conscientious objector may have seemed oxymoronic. Yet by 1965 the Vatican had issued, in Gaudium et Spes, [Joy and Hope: The Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World] an “unequivocal condemnation” of the use of indiscriminate weapons against civilian populations. (146) Interspersed throughout this storyline are Merton’s struggles with official Catholic censors as he navigated each side of the spiritual discipline of being a monk. On the one hand, Merton assented to his abbot’s discipline in not publishing his anti-war writings from 1961 and 1962, including Peace in the Post-Christian Era, his major critique of just war theory and call to spiritual arms against nuclear weapons. On the other hand, his abbot acknowledged the fruits of Merton’s personal spirituality in allowing the book to circulate in mimeographed format. Forest quotes extensively from all of these censored writings to expand their circulation today.

Two other narratives trace the growing resistance to the Vietnam War in tandem with Merton’s widening influence. The most personal moments in the book are Forest’s account of his struggles in launching the Catholic Peace Fellowship in 1964 with Tom Cornell. At the time few Catholics (indeed few Americans) opposed the Vietnam War, and the organization had almost no funding. Forest’s trials seem more psychological, however, including anxieties soothed and stoked by his correspondence with Merton. One of the book’s final chapters, “Letter to a Young Activist,” republishes a moving letter from Merton counseling Forest to treat activism as an apostolic work of witness as opposed to “the myth of ‘getting results.’” (194) Yet Merton also shared his concerns, including the worry that the Fellowship’s educational mission might be hurt by Cornell’s participation in a 1965 draft-card burning protest. Unlike Dorothy Day who attended this protest in support, Merton resisted the civil disobedience of burning one’s draft card. But Merton never retreated from his peace work, which extended into inter-religious dialogue. A reader of Buddhist, Hindu, and Sufi spirituality, he met a fellow-traveler in Thich Nhat Hanh [See Jim Forest's article on Hanh here], the Vietnamese advocate of socially engaged Buddhism who advanced peaceful solutions that pleased neither the North nor the South Vietnamese governments. Politics, like war, often runs on fear. They each trade in insular myths of the righteousness of one’s side, a mentality that demands all of the efficiency and power of technological, bureaucratic, and military systems to guarantee security for “all.”

While the issues in the United States have evolved—the nuclear arms race and the Vietnam War have given way to the “war on terror” and conflicts with Muslim-majority nations—Forest’s account of the self-perpetuating dynamic between fear and security is timely. It remains urgent to question the rhetoric of security and what Forest calls “the industrial impersonality of modern war.” As Merton observed, “There is not even much hatred in [modern warfare]. If there were more hatred the thing would be healthier.” (6-7) Indeed, as remarked by comedian Bill Maher and gruesomely exhibited by the human butchers of the Islamic State, the distancing technology of cruise missiles and drone strikes produces a detached sense that the enemy is not even worth the emotional energy of hate. The other merely represents a threat of difference to be exterminated at all costs.

Forest’s dual emphases on war and fear give the book coherence, but raise questions about what he omits from Merton’s writings and how he frames Merton’s advice to peacemakers. Forest focuses on war—so much so that the book hardly mentions the Civil Rights Movement, though Merton praised it as “the greatest example of Christian faith in action in the social history of the United States.” (1) Peacemaking involves more than pacifism in the sense of opposition to war. Merton himself acknowledged the importance of building institutions that support social justice. Yet even Merton seems reticent to condone acting strategically, let alone acting provocatively as in the case of burning one’s draft card. Instead, the “spiritual roots of protest” are nurtured by radical openness to God’s love throughout one’s life and relationships, leaving no room for strategy or efficacy. As he put it in 1967, “Nonviolence does not say ‘We shall overcome’ so much as ‘This is the day of the Lord, and whatever may happen to us, He shall overcome.’” (175) It is difficult not to read this statement as an implicit disagreement with some of the strategies commended by Martin Luther King, Jr. and used by Civil Rights protestors. Economic boycotts and rent strikes not only provocatively challenge the powerful, but they can also result in indirect harm.

Turning to fear, Forest presents Merton as affirming the universalistic claim that every person stands in the same position of fearing the other as a result of self-justifying fantasies about one’s goodness. Shortly before reading Forest’s book, I finished Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me, a public letter to his teenage son about the dangers of being black in the United States. I was struck by a shared thesis between the two books—that fear is the root of violence. For Coates, however, fear comes in different forms. He chronicles two types of fear in particular. On the one hand, the fear that many African Americans have long felt in America is warranted, yet rarely does it cause harm beyond the contorted bodies and lives that black people adopt so as not to offend the enforcers of the white American dream. On the other hand, there is the fear projected onto African-Americans by, in Coates’ words (quoting James Baldwin), the people “who believe they are white.” (2) This second fear justifies violence against black people, and its projection mechanisms parallel the fear that Forest identifies as the root of war. Forest’s exclusive focus on the latter type of fear feels constraining by the book’s end, leaving this reader with the following question. Although Merton understood fear as a cultural production, did he address the ways that fear differs with social location? My sense from reading Forest is that Merton saw fear and love in universal terms. Violence is a product of fearful hearts needing God’s love. If so, then I see Merton as too hopeful that changing hearts will unlock structural injustices and insufficiently aware of how implacable the powerful can be or how healing it is to assert one’s self-worth against society’s dominating fears.

With Forest providing a front-row seat, Merton’s advice to peacemakers and his influence on the Catholic Church are made vivid in their historical contexts. I recommend that readers embark on this accessible and engaging journey through Merton’s writings and draw their own conclusions.

Endnotes:

(1) Thomas Merton, “Religion and Race in the United States,” Faith and Violence: Christian Teaching and Christian Practice, Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1968.

(2) Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me, New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2015; 133.

EDITOR’S NOTE: David M. Craig is Professor of Religious Studies and Chair, Department of Religious Studies Indiana University-Purdue University. His books include Health Care as a Social Good: Religious Values and American Democracy, Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2014, and John Ruskin and the Ethics of Consumption, Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press, 2006.