by Terry Messman

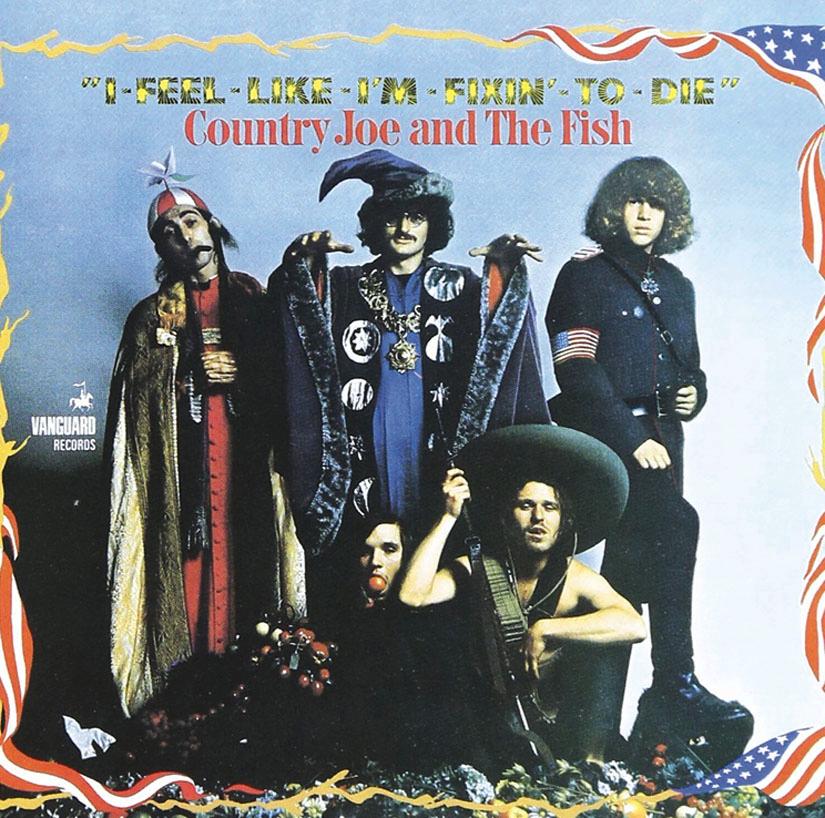

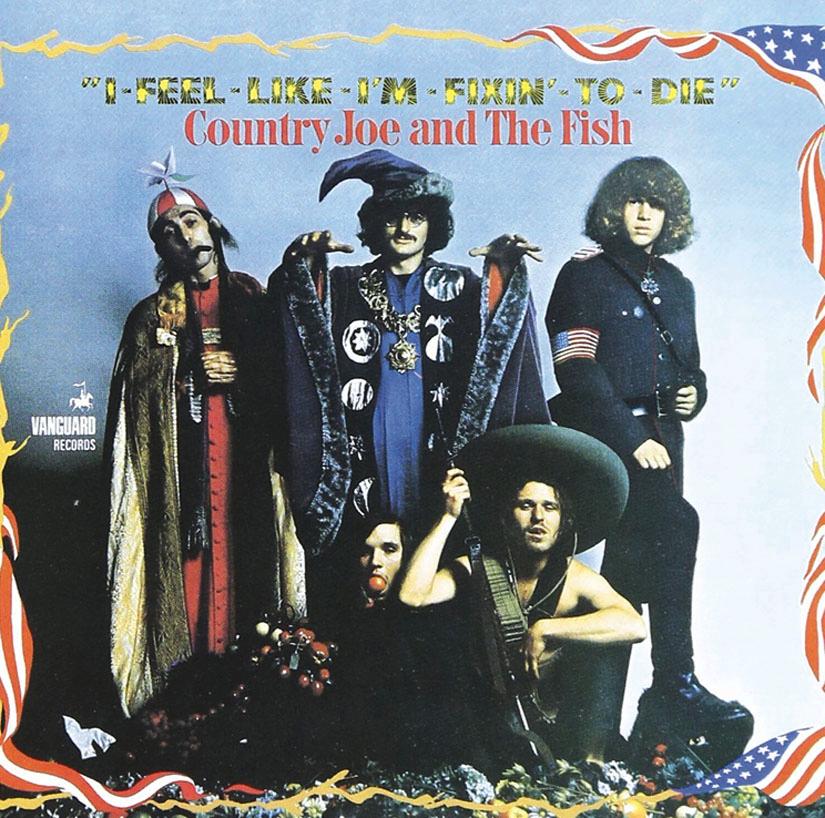

The second album Country Joe and the Fish album; Country Joe is seated front far right; courtesy thestreetspirit.org

“Women coming home from the Vietnam War never were the same after their wartime experiences. They were shoved into a horrific, unbelievable experience. That’s what I wrote about in the song: ‘A vision of the wounded screams inside her brain, and the girl next door will never be the same.’” Country Joe McDonald

Street Spirit: You first sang “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” on the streets of Berkeley during the Vietnam War in 1965. Fifty years later, you sang it at an anti-nuclear protest at Livermore Laboratory on the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Could you have imagined in 1965 that your song would still have so much meaning today?

Country Joe McDonald: Actually, I find the concept of 50 years incomprehensible. But it’s indisputable because I have children and some of those children have children and I know that the math is right. And I just finished an album and the title of it is 50 because it’s 50 years since the first album. It’s called Goodbye Blues. I didn’t die, so there you are. I’m still alive and I’m still doing something. Filling a need helps a lot, and it keeps me sane.

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

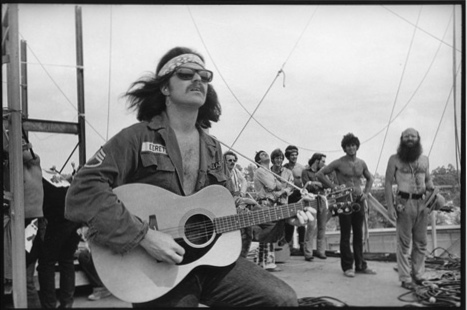

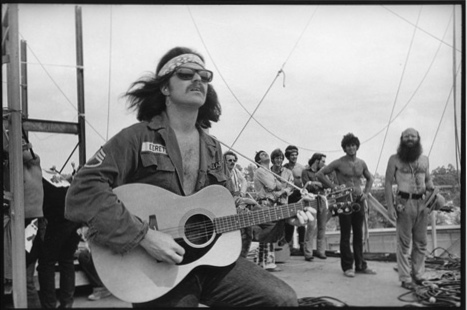

Country Joe McDonald sings “Fixin’ to Die Rag” for 300,000 people at Woodstock; photo by Jim Marshall, courtesy thestreetspirit.org

“It was magical. All at the same time, amazing stuff happened in Paris, London, and San Francisco — and BOOM! Everybody agreed on the same premise: peace and love. It was a moment of peace and love. It was a wonderful thing to happen. And I’m still a hippie: peace and love!” Country Joe McDonald

Street Spirit: During the Vietnam War, and while caring for the victims of PTSD and Agent Orange in the years after the war, Lynda Van Devanter and other Vietnam combat nurses helped many veterans to survive. Your song about Van Devanter says that the combat nurse is everybody’s savior but her own. Then it asks, “Who will save her now?”

Country Joe McDonald: Yes, who will save her now?

Read the rest of this article »

by Terry Messman

Country Joe McDonald sings anti-war songs; Livermore Lab, Hiroshima Day, August 6, 2015; courtesy thestreetspirit.org

Country Joe McDonald composed one of the most acclaimed peace anthems of the Vietnam era, “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag,” a rebellious and uproarious blast against the war machine. The song’s anti-war message seems more timely than ever, with its savagely satirical attack on the arms merchants, the military and the White House. “Fixin’ to Die Rag” condemns the architects of war and the military-industrial complex in bitterly sarcastic terms.

Come on Wall Street, don’t move slow

Why man, this is war au-go-go!

There’s plenty good money to be made

By supplying the Army with the tools of its trade.

Recently, a major new book by Craig Werner and Doug Bradley, We Gotta Get Out of This Place: The Soundtrack of the Vietnam War, [Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015] ranked hundreds of Vietnam-era songs and listed “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” by Country Joe and the Fish as one of the two most important songs named by Vietnam veterans, right after “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” by the Animals. “The soldiers got it,” write co-authors Werner and Bradley about Country Joe’s song. Michael Rodriguez, an infantryman with the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines, said: “Bitter, sarcastic, angry at a government some of us felt we didn’t understand — ‘Fixin’ to Die Rag’ became the battle standard for grunts in the bush.”

Read the rest of this article »

by Rasoul Sorkhabi

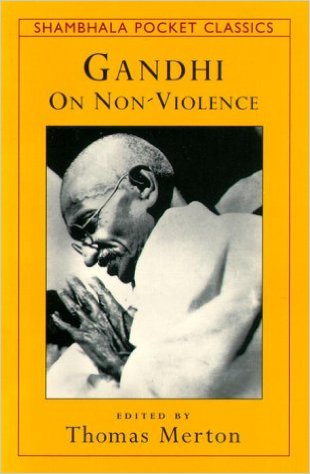

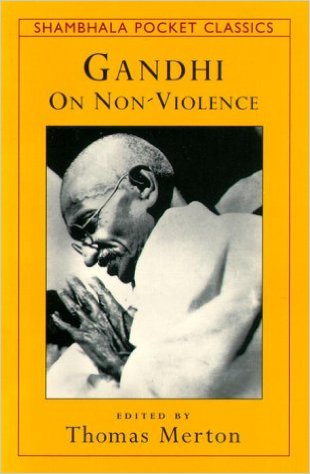

Dustwrapper art courtesy Shambhala Publications; shambhala.com

Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated in New Delhi in 1948 (sixty years ago as of this writing) and the renowned Trappist monk and author Thomas Merton was killed in a tragic accident in 1968 (forty years ago). These anniversaries are valuable opportunities to reflect on the legacies, works, and teachings of these two great men of peace. Gandhi has influenced many minds and movements of the twentieth century. In this article, we review Merton’s impressions of Gandhi and how they are helpful for our century and generation.

Thomas Merton, born in 1915, was 46 years younger than Gandhi. Merton spent the first two decades of his life in France, UK and USA. In 1939, he received his MA in English literature from Columbia University, and the following year accepted a teaching position at the Franciscan run Saint Bonaventure University in southwest New York State. In 1942 he decided to become a priest and entered the Abbey of Gethsemane, a Trappist monastery in Kentucky; the Trappist are strict observance Franciscans, and having taught at St. Bonaventure might have influenced his decision. Merton, or rather Father Louis as he was to be called at Gethsemane, lived the rest of his life there, a quiet and contemplative life in an inspiring natural environment. He kept journals and published innumerable essays, poems, and books. His autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, published in 1948 became a best seller. In the 1960s, Merton was attracted to Eastern religious thoughts and traditions, including Gandhi’s ideas.

Read the rest of this article »

by Tristan K. Husby

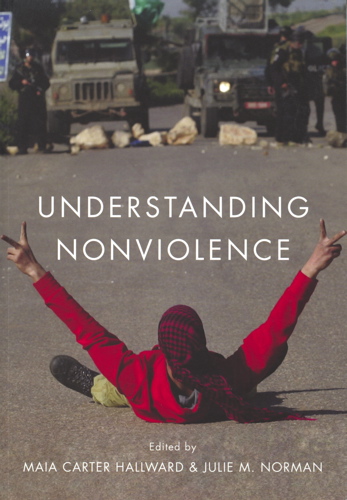

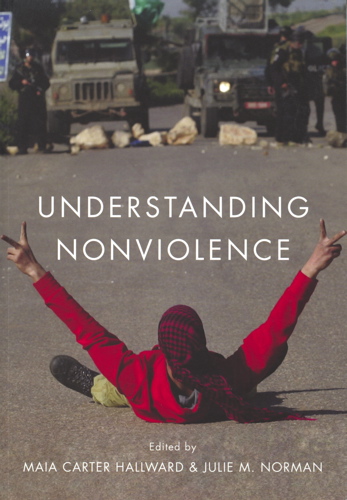

Dustwrapper art courtesy Polity Press; politybooks.com

The phrase “Those who can’t do, teach” is so well ingrained in the English vernacular that there is a range of variations, such as “Those who can’t teach, go into administration” or “Those who can’t teach, teach gym.” Knowledge of this phrase is so widespread that a current sit-com about incompetent teachers is simply titled “Those Who Can’t”. Less well known is that the Irish intellectual, playwright, and wit George Bernard Shaw coined this phrase. His original rendition, “He who can, does. He who can’t, teaches”, was one of the aphorisms in his Maxims for Revolutionists. Another axiom from the same book is “Activity is the only road to knowledge.”

That last sums up a great deal of the history of nonviolence. For to a great degree the history of nonviolence is a history of organizers, activists, and leaders first teaching others why nonviolence is an effective method and then working together with those people for change. The recent anthology, Understanding Nonviolence, edited by Maia Carter Hallward and Julie M. Norman (Malden, MA: Polity, 2015) aims to help aid in the discussion; it is explicitly pedagogical, with discussion questions and suggestions for further reading included in each chapter. Furthermore, jargon is kept to a minimum and the authors use endnotes sparingly. However, labeling this book as pedagogical does not mean that it is contains exercises for training nonviolent actions or flowcharts for planning strategies. Rather, this book is pedagogical in that it aims to help students study nonviolence.

Read the rest of this article »

by Surur Hoda

Dustwrapper art courtesy Harper Publishing; harpercollins.com

Gandhi’s visions of Gram Swaraj, self-sufficient but inter-linked village republics with decentralised small-scale economic structures and participatory democracy, left him immediately at odds with those in and outside the Indian National Congress who were seeking to develop India into a modern industrial nation state. To Gandhi, political freedom was merely the first step towards attainment of real independence, namely social, moral and economic freedom for seven hundred thousand villages. ‘If the villages perish India will perish,’ he had said. But the majority of academically trained, modern economists called his vision ‘retrograde’. Some extremists even described it as ‘reactionary’ or ‘counter-revolutionary’ and accused him of aiming to put the clock back.

Many of those who admired Gandhi’s skill in leading the struggle for national liberation reluctantly tolerated his economic views as the price to pay for his political leadership. They were sold on the concept of large-scale urban industrialisation and mass production. They failed to understand Gandhi’s economic insights and criticised him by saying ‘Whatever Gandhi’s merit as “Father of the Nation”, he simply does not understand economics.’

Yet almost a quarter of a century after Gandhi assassination, the German born economist E. F. Schumacher, when delivering the Gandhi Memorial Lecture at the Gandhian Institute of Studies at Varanasi (India) in 1973, described him as the greatest ‘People’s Economist.’ In his opening remarks, Schumacher told this story: ‘A famous German conductor was once asked who he considered the greatest of all composers. “Unquestionably Beethoven” was his answer. He was then asked, “Would you not even consider Mozart?” He said, “Forgive me. I thought you were referring to the others.”’ Drawing a parallel Schumacher said the same question might he put as to who was the greatest economist. ‘Unquestionably Keynes,’ he would reply, and be immediately asked, ‘Would you not even consider Gandhi?’ His answer would be, ‘Forgive me, I thought you were referring to the others.’

Read the rest of this article »