Seven Reflections on the Enigma of a “Nobody” Making a Public Display

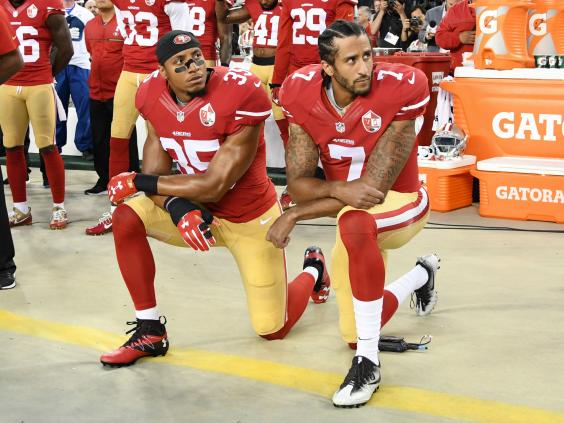

Colin Kaepernick and Eric Reid of the San Francisco 49ers kneel in protest during the national anthem prior to playing Los Angeles Rams in NFL game; courtesy Getty Images

(1) New forms of nonviolent protest, and renewed uses of old forms, are in the headlines; the kneel-in, for example, a protest that has recently spread among athletes. Many people are not aware of the history and the philosophy involved. Not knowing the background, some critics misunderstand and grow angry. Even the liberal and usually knowledgeable Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg called the kneel-in “dumb” and “disrespectful.” (Soon thereafter she took it back: “Barely aware of the incident or its purpose, my comments were inappropriately dismissive and harsh.”) Many people seem unable to put kneel-ins in a historical perspective. So I feel it might help deepen our understanding to look into the background, the meanings, and intentions of some of these practices. Maybe being better informed could help critics comprehend what is happening. (1)

A recent headline in my local paper had caught my eye. It was about the college football players who ‘Take a Knee’ instead of standing and singing the national anthem with all the other players and fans. Amherst College football players were the first in Western Massachusetts to stage this kind of public protest during the national anthem, in 2016. (At Amherst college the previous year there were sit-ins on campus at Frost Library, and a movement grew, “the Amherst Uprising,” whose activism led to the dropping of “Lord Jeff,” the Amherst mascot based on a historical figure, Lord Jeffrey Amherst, who advocated giving smallpox-infected blankets to Native Americans in the 18th century.) In the context of those recent events and other civil rights activities going further back in time we can see that Amherst football players silently kneeling during the national anthem at football games are part of a continuum—these are not isolated acts.

The football players “take the knee” out of specific concerns, such as police brutality, the murder of innocent black men, racial profiling, the marginalization of the black community, and the rash of recent shootings around the country by security and police officers. Some players during the singing of the anthem go down on one knee, silently kneeling, while others also protesting remain standing and raise their fists, in the black power gesture. The black power stance, with arm raised and fist clenched, was first used at the Olympics in 1968 by black medal winners Tommie Smith and John Carlos.

One Amherst football player, A. J. Poplin, eloquently explained by using the lyrics of the anthem itself: “The last words [of the national anthem] are ‘the land of the brave and the home of the free.’ And if I’m not feeling free, I’m going to have the bravery to stand up for what I truly believe in.” It’s a wise move, helping us think about the anthem’s meanings, not just mechanically mouthing the words out of habit. (2)

The symbolic nonviolent act of athletes kneeling was part not only of recent protests, but also part of a continuum that goes back to civil rights protests of the 1960s, and also further back, to Gandhi’s activism. To sit during the anthem is a peaceful strategy to promote awareness and change. In the “sit-in” type of demonstration the idea is to stop the flow of business-as-usual and call attention to an issue of injustice with a symbolic confrontation which is not armed or angry (a potential sign of violence) but is peaceful.

It is also a publicity-garnering act. It makes news because photographers and reporters note it, the story appears on TV and radio, etc. In the ‘60s the “Human Be-in,” and the “Love-in,” were more celebrations than sit-ins, but the “Bed-in” staged by John Lennon and Yoko Ono focused public attention on the Vietnam War civilly, without resorting to disturbing the peace too much. At the 1969 Bed-in for Peace John and Yoko’s rhythmic Mantra-like music repeated the refrain “All we are saying is give peace a chance.”

The sit-in was a well-known method in the American civil rights struggle of the 1960s. But it had already been used in 1939, the 1940s and 1950s, although those protests are not as well known today as the larger scale activism of the 1960s. The many sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in the South called attention to violations of civil rights in many restaurants in the 1960s. The 1960s and 1970s saw sit-ins being used by the feminist movement, the disability rights movement, and transgender rights movement. (3)

In 2016 a civil rights protest veteran, congressman John Lewis (D Georgia), sought to call attention to the lack of attention being given to gun violence in the US. In a sense, the challenge for John Lewis was to figure out a new way to formulate the situation, to state and get across the idea, to answer the question, “How can we demonstrate it’s possible to seek and explore nonviolent solutions, and make a step toward sensible gun control laws?” For one thing, Lewis organized a sit-in in the House of Representatives on June 23, 2016.

When Lewis appeared on the Steven Colbert show on August 31, 2016, to promote his new three-volume graphic history of civil rights, entitled March, (with volume one published in 2013, volume two in 2015 and volume three in 2016), he was asked by Colbert, “You organized a sit-in at the House of Representatives. What was the goal?”

Lewis explained it in this way: “To dramatize the need that we had to do something about gun violence. Sometimes you have to find a way to get in the way, get in trouble, good trouble, necessary trouble. [#GoodTrouble is a hashtag Lewis began using on Twitter, “encouraging all of us to get into #GoodTrouble, to fight for what we believe in.”] I was taught by the older generation [Lewis was born in 1940]: ‘Don’t get in trouble, don’t get in the way.’ But Rosa Parks inspired me to get in trouble. You have to inspire people. So I led a sit-in on the floor of the House of Representatives.” (4)

House Speaker Paul Ryan accused the sit-in protestors of sowing “chaos,” and called it a publicity stunt. “Republicans had earlier tried to shut down the sit-in, but the Democrats’ protest over the lack of action on gun control lasted for more than 24 hours. House Democrats were looking for votes to expand background checks and ban gun sales to those on the no-fly watch list. In the middle of the night, the House GOP had sought to end the extraordinary day of drama by swiftly adjourning for a recess” that would last through the 5th of July. (5)

So if I may elaborate on this serious issue and the hopeful solution Lewis formulated, I would put it this way. In a system in which obstructionists blocked the path what method might work to bring changes, to make a difference? When people are standing in the way of change, activists need to get in the way, not accede in accepting their stagnation, but to get in the midst of things. To be there, not to act aggressively but to be persistently present and wait patiently for a development, to call attention to the issue and get in the way of a dangerous gun violence problem that keeps growing—to get in “good trouble,” causing the irritation of those standing in the way, earning the wrath of the do-nothing change-stoppers by getting the message across harmlessly, nonviolently; getting in the way for a cause needing to be expressed, sounding a silent alarm regarding a serious social ill needing attention.

Lewis himself explained in a tweet: “We got in trouble. We got in the way. Good trouble. Necessary Trouble. By sitting-in, we were really standing up” to get his point across.

Looked at from this view, the obstructionist Republican senators were the ones in the way, making bad trouble through their inaction. Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Gandhi were examples of good troublemakers. To “be in the way” means ordinary activities can’t proceed unless something changes. John Lewis found simple clear ways of getting his point across, and this is a necessity for good “troublemakers,” or “agents of change.” Things catch on by being stated in catchy ways. BB King wrote and sang a blues song in 1962: “I’m gonna sit-in till you give in, and give me all your love…” The idea of the sit-in is to make a display that dramatizes the attitude of persevering in one’s dogged stubborn resistance, remaining focused with patient determination, and BB King dramatizes that in the refrain of his song.

When Rep. Lewis was asked by Colbert about the recent protests of football player Colin Kaepernick, the 49ers back-up quarterback who first started sitting during the national anthem at a pre-season game, Lewis explained “Sometimes you have to get in the way and get in good trouble to dissent, to act according to the dictates of one’s own conscience.” Actually, Kaepernick was soon kneeling on one knee, not sitting, and other players were joining him, including soccer players (for example, women’s soccer star Megan Rapineau), and high school athletes and college athletes, during their games around the country. Such purposeful non-cooperation by athletes seeks to call attention to an issue of injustice to minorities. It has caused an angry stir in some minds, as if many sports fans had never heard of a sit-in, or could not imagine how this peaceful symbolic act could be anything but an insult to the flag and U.S. servicemen. As if patriotism means conforming and kneel-ins offend.

(2) Another example from another field of activity is valuable to consider as well: Karim Wasfi’s way of sitting-in while performing music. Wasfi is a public figure in Iraq who uses music in his activism for peace. In 2015 he began going to the streets in Iraq to play the cello after acts of violence such as bomb explosions destroyed lives there. He speaks of the importance of “respect for life” as opposed to the forces representing crude brutality, which he calls “ugly new ways to kill and destroy.” “Respect for life” is a reverence, an attitude of caring for others’ wellbeing, a sense of life’s sacredness.

Asked why he went to a street and played his cello there after a car bomb exploded, Wasfi said: “It’s partially the belief that civility and refinement should be the lifestyle that people need to nurture and consume and, in order to achieve that, I think arts in general, and music in particular, is a great way to convey such a message. It was an action to try to equalize things, to reach the equilibrium between ugliness, insanity and grotesque, indecent acts of terror—to equalize it, or to overcome it, by acts of beauty, creativity and refinement.”(6)

Each generation needs to rediscover the perennial wisdom of nonviolent protests, and the protests need to take different forms in responding to the issues to be effective.

Similarly, Sioux and other Native-Americans at Standing Rock in the summer of 2016 staged “peaceful prayerful standoffs” to protest an area of ancestor burial places where a pipeline was being placed underground. “Peaceful” and “prayerful” are terms to remind all that the issue is a matter of conscience, nonviolence and faith. The Occupy Movement is another example of protesting economic and political issues. Such activities involve personal activities rediscovering what democracy meant before it was taken for granted—involvement, discussions of concerns, seeking consensus, individual voices being heard. Sometimes Occupy protestors have been forcibly removed, but their acts are a part of the history of standing up for serious concerns.

(3) People are susceptible to waves of hysteria, rashes of violence, and may not have the presence of mind to realize that a philosophy offering another method might succeed without the bloodshed which violent clashes and attacks bring. The verb “to not cooperate” suggests a spectrum of non-actions: to withhold participation, to refrain from action, to renounce harming the oppressor and to abstain from work that keeps the oppressor in power. To not show up. Or to show up and just sit there. A sit-in can create a dramatic protest against injustice, making a demand, by just sitting still in a place where one is not supposed to be. Not to vandalize or bomb, not to assassinate or attack, but to confront and wear down the oppressor with sheer stubbornness. The protestors’ bodies present themselves together all of a sudden, confronting injustice, causing oppressors to stop and think about an issue they’re allowing to exist, an oppression they are sometimes perpetuating without even consciously realizing how unjust and offensive it is. The sit-in protest makes a demand: “Rethink this. Consider alternatives to this unsatisfactory situation. Stop, join me in recognizing this issue.”

Precisely aimed, certain kinds of “non-action” can make an impact. This can be a real option. The power of not doing things can be a unique pressure which time and again over the ages spiritual-minded people have made use of, and many people in the modern age have tended to underestimate. In an age of materialism many take for granted cynical views, such as “Might Makes Right” and “The golden rule means he who has the gold makes the rules.” But just as peace or health are positive, dynamic, generative, vitalizing, not merely an absence of war or absence of illness, so too nonviolence as Gandhi saw it can be a potent force for fuller life. Gandhi once quoted an ancient seer: “Not through violence, but through nonviolence, can persons fulfill destiny and duty to fellow creatures.” Just as electricity is an invisible and mysterious force, so too is nonviolence in Gandhi’s view. His experiments showed him that “at the center of nonviolence is a force which is self-acting.” There is vitality in the principle of nonviolence, which entails a life-supportive philosophy. When invited to the U.S., by African-Americans who met with him in India, Gandhi answered that blacks in America might be the ones destined to give the message of nonviolence to the whole world. Gandhi voiced that wise hope.

(4) Some may ask, “How do we know it wasn’t just wishful thinking and a coincidence, this idea that Gandhi’s ahimsa philosophy prevailed when India won self-rule from England? Maybe the time was just ripe for it, or the British were sick and tired of the charades of colonialism, or some other factors were at play?” Gandhi’s perspicacity, envisioning the method to do the greatest good with the least harm, benefiting all concerned, was not just magical wishful thinking, because it was tried out over the years in experiments, tested and proven. It is a philosophy, but it’s been strenuously followed over time, tracked and tuned. It was not just a coincidence he was at the helm when India gained independence. His nonviolence was a unique method, which he held dear for a lifetime. A great change through a “nonviolent revolution” (though of course many Indian lives were lost because of British violence) does not happen by accident. It was not a coincidence that Gandhi’s path arrived at Independence, and it is not a coincidence that nonviolent movements have a track record of success. Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, in a recent comparative study of violent and nonviolent movements entitled Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, compared 323 violent and nonviolent struggles over the period from 1900 to 2006. They did not attempt to examine all forms of nonviolent struggle in their study; they confined their work to anti-regime, anti-occupation, and secession movements. (7)

They report, “The most striking finding is that between 1900 and 2006, nonviolent resistance campaigns were nearly twice as likely to achieve full or partial success as their violent counterparts…in the case of anti-regime resistance campaigns, the use of nonviolent strategy has greatly enhance the likelihood of success. Among campaigns with territorial objectives, like anti-occupation or self-determination, nonviolent campaigns also have a slight advantage.” Gandhi proceeded with very careful acts and non-acts, such as refusals to cooperate, decided upon at every step of the way, knowing human nature, and praying for wisdom and help from beyond one’s own ken to win a peaceful resolution.

The “not-doing” component of non-cooperation involves a peaceful untangling, the untying of a knot. The Tiananmen Square pedestrian tank-stopper who did not move, but dared to linger in the path of danger, to stand still. He failed to win over the authorities in China, but he became an icon of nonviolent persistence in the world’s memory. He performed a confrontation but not exactly a taunting, a gentle appeal not venomously daring the “other” to attack and destroy. It was a testing of boundaries, a silent reflection on how to dissolve boundaries. Above nature’s fray, not bloody in tooth and claw; harmless and loving, not sharp-pointed and defensive. It was like Kent State in the 1960s, when war protestors put flowers in rifle barrels. Being there as an aware witness, instead of reacting, threatening or even thinking of aggressing, involves hoping to reach a meeting of the minds, raising awareness, not poisoning thought with bitterness.

(5) Let’s explore the further power of carefully aiming the impact of refraining from action. The humorous reversal of the saying “Don’t just sit there, do something,” is “Don’t just do something—sit there,” used by Baba Ram Dass to advocate meditation. That kind of non-active stillness is well known in Taoist and Buddhist traditions. It is not nihilism, because sitting there is not literally nothing. It is a focus on the human potential of higher consciousness. It is a practice of calm, a defense against panic. Conscious use of the absence of aggressive resistance is cooperating with nature and time, “coercive” in allowing nature take its course to change the mind of the opponent. The opponent is to be respected; he’s the fellow human being we inter-exist with, whose dignity and well being, like our own, we hope will flourish. In India there is an ancient prayer, “May everyone in all the worlds be happy” and Gandhi took that magnanimous idea seriously.

It’s a lesson humans learn, forget, and learn again. Not doing things has a power. In Aristophanes’ 2400 year-old play Lysistrata, Greek women, knowing the nature of their men, refused their advances and withheld sex from husbands and lovers until peace negotiations brought an end to the Peloponnesian war. In that story the refusals of the women overcame the aggressions of the men. Non-cooperation with violent enterprises has been a method used for millennia, in various forms. In 1968 a group of writers in the U.S. refused to pay federal taxes, to protest the war in Vietnam. American philosopher Henry David Thoreau was a writer who tried that strategy generations earlier, going to jail in 1846 for refusing to pay his poll tax. Why? To be loyal to his anti-slavery beliefs.

When Gandhi wrote on the last page of his Autobiography: “I must reduce myself to zero,” he was following the ancient Hindu yogic path, and the Buddhist and Jain practice, saying ego and desires cause suffering. He was pointing to the spiritual idea of finding self-fulfillment in the larger vision of being one with all life, avoiding a sense of isolation and self-importance. By sublimating the ego, he was trying to make himself not a self-server but a selfless server of the common good. For a person of dedicated action, a karma yogin such as Gandhi, being “nobody” meant stepping out of the way, being a selfless helper of justice, one whose ego’s personal likes and dislikes do not get in the way of helping victims of injustice.

The nature of the ego causes the egotistical person to always be proving he’s important, somebody big. There are many tyrants in history and in current events who are vivid examples. Gandhi wanted to do the work of leadership without the burden of ego.

The nature of humility and honesty lends itself to negatives, and to amused reflections on the advantages of being a nonentity—take Emily Dickinson’s gem of a poem:

I’m Nobody! Who are you?

Are you—Nobody—too?

Then there’s a pair of us!

Don’t tell! They’d advertise—you know!

How dreary—to be—Somebody!

How public—like a Frog—

To tell one’s name—the livelong June—

To an admiring Bog! (8)

The inward-turned poet reflecting on elusive aspects of life experiences is really not much concerned with public opinion. It is more liberating when one humbly identifies with being “Nobody” and it is a burden to be too concerned with what the fickle masses like or dislike, applaud or boo. To erase ego is to claim true individuality.

Someone who is humble, wide of sympathy and big-hearted, lacking in ego, might seem vulnerable to thick-skinned violent people. After 9/11 an organization called “Artists for Peace” made a sign. “My grief is not a cry for war” the sign insisted. They wanted to make the point that the nation’s leaders should not assume that the artists wanted war to redress their losses. Politicians were saying that to get revenge for the losses of the attack the nation had to go to war. Throughout the Iraq war there was a drumbeat—“So that the blood already shed is not in vain we must keep using violence to fight the enemy.” As if the leaders assumed that all sane people would want war. But there were differences in personal responses to this idea/policy. And so, to set the record straight the Artists for Peace, wounded by personal losses, yet seeking no revenge, put into words their choice, refusing the call for violent acts of war to get back the irreplaceable. They had other views, nonviolent ideas. They summed up their point well—they felt grief, but did not want war.

(6) Consider the multiple forms of refusal in colonial India, too, when Gandhi and others wanted to be free of British rule but not at the price of violence. Refusing to be coerced by the British government was one method, articulated as a resolution by the Indian National Congress which urged “non-cooperation.” This meant the boycott of (refraining from buying) British goods; and Indian VIPs renouncing (returning to the giver) British titles; Indians would refuse to attend government schools, refuse to pay taxes, refrain from participation in British dominance in whatever ways were possible. The first major public act of non-cooperation was a hartal (a strike, abstaining from work), a strategy to disrupt business-as-usual in the British colonial order of everyday life.

The hartal was a show of unity, and it involved a “sacred fast.” Going without food for spiritual reasons was an old practice in Hindu traditions. Gandhi as a youth often saw his mother observing days of fast. To not eat, to “suspend business,” to close up shops and not conduct usual work and activities, all these were non-actions. They were refusals, abstentions, withdrawals, unknottings. Abstaining from British clothing meant spinning cotton oneself, which Gandhi encouraged for the whole nation, to be free from depending on England. Gaining self-rule involved autonomy expressed in self-control, self-restraint.

“Civil Disobedience” (another term in Gandhi’s vocabulary, which he possibly first encountered in reading Thoreau’s writings) is another term for some aspects of refusal, and sometimes unlawful nonviolent protest. Civil Disobedience takes many forms. At one point it might involve a procession; it can also take the form of quietly stopping one’s actions when one is expected to do one’s duties, not responding to being assaulted by security forces. The impact of India grinding to a halt one day showed British rulers that the everyday flow of life depended on the whole population of Indian people working together. It was a wake-up call for the British—and also for the people themselves. It brought home to them the taken-for-granted fact that they were not helpless, they were the ones who grew the food, sold it at stores, delivered the goods and performed the services all across India.

Not eating (fasting), ahimsa, nonviolence, non-cooperation, civil disobedience, non-resistance—these basic “negative” principles provided a way toward positive steps toward self-rule, India’s independence. Gandhi, realizing he needed to include the millions of Muslims in India in the activism for independence, found the words Muslims in India would understand—ba-aman for ahimsa, nonviolence. And tark-i-vavalat for non-cooperation. Teachings of nonviolence and non-cooperation gave a peaceful identity to the movement. Non-belligerence, non-aggression, respect for the opponent—the winning of freedom required such a vocabulary for virtues and practices like these.

(7) In the West, people often think of transcendence as going to a place—such as to heaven, another realm up above. But in Asian wisdom, transcendence is often described by words expressing what it is not: timeless, formless, changeless, indescribable, peace. Nirvana, the Buddhist concept of transcendence, is described by what it is not. The word means “blown out,” referring to extinguished flames of passions and sorrows, loss of agitations and desires; it means “gone beyond the strife.”

Language itself has a richness, an ability to reveal new ideas, suggest new resources for thought. The English word “innocent” is a western term similar to ahimsa (“nonviolence”)—it has a “negative root” because it points to something that is not. At root it means both “unhurt” by others and “not harming” others, being free of guilt and “not noxious.” Ahimsa is an ancient principle, a virtue in the shared vocabularies of Hindu yoga, Buddhist ethics, and Jain practices.

When I interviewed the great African-American writer Albert Murray in Harlem he discussed methods of nonviolent civil disobedience as “political jujitsu” because it involves not avenging an oppressor by forcefully striking, not deliberately hurting, but getting out of the bully’s way, being an empty space where the aggressive attacker trying to harm you loses balance and falls of his own weight. (The Quaker lawyer and leading American thinker on nonviolence, Richard Gregg, coined the term “political jujitsu” in 1934.) By being fast enough to “disappear”— not literally, but seemingly—you precipitate a downfall of the assailant. “The bigger they come, the harder they fall,” as the saying goes, because bullies lose balance.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote, “The ultimate weakness of violence is that it is a descending spiral, begetting the very thing it seeks to destroy. Instead of diminishing evil, it multiplies it. Through violence you may murder the liar, but you cannot murder the lie, nor establish the truth. Through violence you may murder the hater, but you do not murder hate. In fact, violence merely increases hate. So it goes. Returning violence for violence multiplies violence, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness: only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate: only love can do that.” And love is ahimsa, non-harming, caring about others’ well being.

Charles Darwin noticed that motherly love is one of the most powerful emotions, yet is the most invisible of emotions; it is quiet, it does not draw attention to itself. No outward signs or dramatic gesticulations, as in emotions of anger and fear, no sound or motions as in erotic love. The feelings may not even show much in the face of the mother. Yet motherly love is wise, nurturing, sustaining, helping, able to reconcile and harmonize differences. Motherly love is broadminded, magnanimous, protective of all concerned.

We are used to thinking of spectacular display and ostentation as signs of importance.

No doubt to some people nighttime and sleep—when nothing much is visibly happening —seem like a waste of time in unproductive non-events. And no doubt to some, winter is a time when nature sleeps, and nothing is happening. Yet in sleep the body makes countless repairs, and the unconscious mind works out issues in the plays we call dreams. And without the whole cycle of seasons, including winter, some fruits such as apples, will not grow. Maybe we’re biased against the regenerative powers hidden in quiet processes because we can’t see them. We have to imagine them and value their results. The dynamism of “empty” space is hard to keep in mind. Anthropologist Gregory Bateson liked to remind us of this by pointing to the human hand; it’s not just the five fingers that make it so versatile, it’s also the four empty spaces in between the fingers and the thumb which allow it to accomplish innumerable things.

All the “nons”(nonviolence, non-cooperation, boycotts and strikes, fasting, being present at a sit-in, occupying space with a purpose, militant nonviolent resistance, kneel-ins, etc.) are being rediscovered and practiced in new forms generation after generation. That’s not nothing. Untying knots of grief, refusing to become obsessed with vengeance, and undoing the effects of oppression—these constitute something more healing and hopeful than all the violent acts combined.

Endnotes:

(1) Los Angeles Times, David G. Savage, “Ruth Bader Ginsberg Voices Regret Over Her ‘Harsh’ Put Down of Colin Kaepernick’s Protest” <http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-ginsburg-kaepernick-protest-20161014-snap-story.html> : accessed October 21, 2016.

(2) Daily Hampshire Gazette, September 29, 2016, pp. A1 and A4.

(3) See Wikipedia article “Sit-in” <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sit-in>: accessed October 21, 2016.

(4) A link for this appearance on the Colbert show is: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ATwisIrtfg> : accessed October 21, 2016.

(5) CNN Politics, “Democrats End House Sit-in Protest Over Gun Control” D. Welsh, M. Raju, E. Bradner, S. Sloan, <http://www.cnn.com/2016/06/22/politics/john-lewis-sit-in-gun-violence/>: accessed October 21, 2016.

(6) Al Jazeera, “Interview: Why I played the cello at a Baghdad bombsite,” May 28 2015. <http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/04/interview-played-cello-baghdad-bombsite-150429191916834.html>: accessed October 21, 2016.

(7) Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

(8) Academy of American Poets, <https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/im-nobody-who-are-you-260> accessed October 21, 2016.

EDITOR’S NOTE: William J. Jackson is our Literary Editor, and a frequent contributor to this site. Please click on his byline to access his Author’s page, for an index of his articles posted here, and biographical information. His page may also be accessed via the Author Archives link at the top of the page.