Making Our Country a Better Country: The Fellowship of Reconciliation Interview with James Lawson

by Diane Lefer

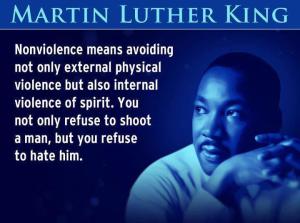

Poster art courtesy fabiusmaximus.com

Editor’s Preface: Martin Luther King, Jr. called James Lawson “the world’s leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence.” To Congressman John Lewis, he is “the architect of the nonviolence movement.” Jesse Jackson calls him simply “the Teacher.” According to author David Halberstam, in his study of the Civil Rights Movement, The Children he was as responsible for sowing the seeds of change in the South as any single person, except perhaps Martin Luther King. This is the third in our series of interviews with Rev. Lawson. Please see the note at the end for further information, and acknowledgments. JG

Diane Lefer: You’ve said we have sufficient activism in this country to have a better country than we have. What are we getting wrong?

James Lawson: Activism has not been appropriating and practicing enough the Gandhian science of social change. What Gandhi called nonviolence or satyagraha – soul force – is both a way of life and a scientific, methodological approach to human disorder. It is as old as the human race and can be found in the oral and written history of the human family from way back. Then Gandhi began to put together the steps you need to take to create change. He is the father of nonviolent social change in the same way that Albert Einstein is the father of 20th-century physics – not the inventor, but the person who pulled it together.

Gene Sharp wrote the classic book in the field, The Politics of Nonviolent Action. Looking at different centuries and different cultures, he discovered 198 different techniques – various forms of protest and agitation and strikes, sit-ins, and civil disobedience, and there are many more because people keep inventing other techniques. Activists ought to study this so they can become like military strategists, not just operating out of the adrenaline that develops out of anger but that puts the anger together with reflection.

Today, much of our activism does not discuss, study, and apply what nonviolence theory offers the struggle. Too much activism gears itself to lobbying legislatures and Congress and the president. That sort of activism does not have the clout that the Council on Foreign Relations has or that Exxon has or the Pentagon has, so it’s lost. We want to leave it to the political parties and to follow their leadership rather than to work on empowerment of the people.

Again and again, when a movement begins to raise its head in the United States, immediately the so-called political social progressive forces try to surround it and try to guide it into the channels they think are important. I experienced this as early as 1961 with what I think to be very wonderful people in the Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson administrations, because there was antagonism to our getting into the streets and marching, and to the sit-ins. Robert Kennedy was mobilizing foundations and others to put money into voter registration. In meetings, he pushed very, very hard and eloquently that we should end the Freedom Rides and go towards voter registration. In 2006, when the coalition of immigration groups came together to start the big marches, they were immediately approached by foundations and political groups that said the way to do this is to lobby for a good bill.

Lefer: But voting rights and voter registration paved the way for the election of Barack Obama. Doesn’t that show we can bring about change through the ballot?

Lawson: Pulling down the White and Colored signs across the country, the No Jews, No Mexicans, No Irish, No Wops, No Indians signs all across the country, did far more to prepare the mind of the nation for a black president than voter registration. Desegregation of the sports world and the university and the professional world did more to prepare the American mind than the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The country has grown since the 1950s and ’60s precisely because we put into play those forces that began the desegregation process – while universal access to the right to vote still hasn’t been achieved in the United States.

Obama is one man. Meanwhile, we are still trying to establish a democracy, amid the chaos and the greed. J. P. Morgan Chase publicly said that the Great Recession [2008] was a great time for them to buy up assets. The bailout was used to give big dividends to their investors. There’s no indication that these engines for self-destructing our country have stopped or slowed down. And while the visible signs of segregation have come down, the systemic stuff is still there. Blacks are still largely the last to be hired and the first to be fired. People still need to be empowered.

Only by engaging in domestic issues and molding a domestic coalition for justice can we confront the militarization of our land. We must confront that here – not over there. Iraq and the Middle East are not the central, pivotal places for the wellbeing of the American people. The violence we’re facing is not the violence over there.

We maintain that we are a culture that has a high regard for the sanctity of life, but we have never had that – and we have never examined our own violence. We have a problem as a culture: we believe that violence is effective. That violence works. We encourage the killing even when we don’t teach it. Our denial is ruthless. And I maintain that there are several other major factors which have taught us to depend upon animosity and violence.

There is what can be called the American Holocaust – the decimation of the Native peoples. Thirteen to fifteen million people! We cut them down in less than 200 years to less than 250,000 people. That has made us sense the efficacy of violence. We stole: we took their land.

Then the establishment of slavery taught violence. It continues to teach violence. Concomitant with slavery was the development of the very rigid ideology of racism and the systems of racism. Part of this comes out of the treatment of the Native American, but for 250 years slavery was justified with the ideology that the slave was out of the jungle, the slave was immoral, the slave was lazy, the slave could not learn, the brain of the slave was smaller, all sorts of stuff that is still the bedrock ideology that has convinced at least 50 million people in the United States of the fundamental inequality of people of color.

Lefer: That’s a shocking figure. I can’t quite believe it. Do you have a source for it?

Lawson: Joe Feagin, who is a sociologist teaching at Texas A&M University, has done a series of studies. He was president of the American Sociological Association, so that surely makes him a reputable source. [For more on this topic see Feagin’s 2006 book, Systemic Racism, London: Routledge, 2006.] He’s not saying, and I’m not saying, that the Ku Klux Klan or the Identity Church or other white supremacist organizations and hate groups have 50 million members. But there are over 900 recognized hate groups across the U.S. today, and they are increasing in numbers. There are 50 million Americans who believe in the superiority of white civilization. And a majority of white people still assert the inherent inequality of people of color. Vast numbers of white people practice a certain degree of graciousness in public life but use racist language in private circles, what you can call “backstage racism.” Sociological studies find again and again that two-thirds of black people experience racial hostility every day. I was speaking recently in Missouri, and my wife and I were staying with a family. The 14-year-old girl came home from school and said her teacher told her, “I’m gonna have to have a lynching party with you,” or “I’m gonna bring you a hanging noose.” And the average American doesn’t know this is going on.

Lefer: But isn’t there a big difference between racism now and the racism back in the 1950s and ‘60s? Didn’t the election of Barack Obama show that things have changed?

Lawson: A majority of whites voted for McCain. The black community, the Hispanic community, the Jewish community and the Asian community voted for Obama by a landslide. Those four groups of people are the most sensitive to the issues of racism. The majority of white people voted twice for George W. Bush.

I maintain that racism and slavery are major contributions to the violent perspective. And sexism is akin to racism. The whole anti-abortion business is but a subterfuge to maintain power over women – to say that women are not equal moral agents in the sight of the Creator as are we men. Various aspects of Christianity teach what they call the “headship” of the male. In 1998 the Southern Baptist Convention adopted that as one of their belief principles, and there are other denominations that have the same principle. The Vatican insists that a woman cannot be called by God to be a priest. But if there’s any task in the world that a woman can’t do, that supports the inequality and submission of the woman – and all of that is a violent perspective. It has continued to encourage family abuse.

Finally, I think a major influence is “plantation capitalism,” with its emphasis on greed. That’s not the Adam Smith form of capitalism.

Lefer: What do you mean by “plantation capitalism”?

Lawson: I do not think that you can have 250 years of a peculiar national institution like slavery without it affecting economic thought or the attitude toward labor. At the heart of plantation economics was the notion that there are people who do not deserve to reap the benefits of their labor. Workers were property, not human. Slaves were paid nothing but subsistence, and died early.

Today you have all kinds of demands on the part of capital that workers are not to receive wages enough to live on. And for twenty or thirty years now a number of reports from nonprofits such as the Rand Corporation – also the World Health Organization and the International Labor Organization – show that with regard to the eradication of illiteracy and poverty, the provision of health care and quality education, the U.S. has moved further and further down in the list of nations. There’s an annual, Worldwatch Institute report, “The State of the World.” It indicates over and over that the United States barometers of wellbeing have lingered behind the advances of Europe and Canada and Japan. Very little of that is ever reported in the American media, so the notion is that we are still the greatest country in the world. Compared with what? Infant mortality? We’re atrocious. Literacy? Health care? Housing? According to the Wall Street Journal, the barometer of wellbeing is not infant mortality but how many millionaires are created. Then they changed it to billionaires. Our social fabric is atrocious. It’s because we’re in the grip of plantation capitalism.

The militarization of the last sixty years has certainly compounded our belief in the efficacy of violence, but these four factors – genocide, racism, sexism, plantation capitasm – are all part of it. These forces have welded the culture of violence.

Focusing Activism, Yesterday and Today

Lefer: The Civl Rights Movement of the 1950’s and ‘60’s has been well documented and David Halberstam wrote a wonderful account of your role in his book The Children (New York: Random House, 1999). He quotes Martin Luther King Jr.’s remark that you are “the world’s leading theorist and strategist of nonviolence.” I’d love to hear about how you’ve applied nonviolent methodology since the Movement.

Lawson: Martin made that remark on the eve of his assassination. On Wednesday, April 3, 1968 he arrived in Memphis and we were having a mass meeting – thousands of people – at Mason Temple. He spoke of me before giving the speech in which he said “I’ve been to the mountaintop.” And the next day…

What King saw in me was that I studied Gandhi and called Gandhi the father of nonviolence but I taught about it from the perspective of Jesus of Nazareth. That was my contribution to the Movement, because we were mostly talking to people who’d been baptized and I had carefully worked on nonviolence from within the Christian tradition and lodged it in Biblical thought. I combined the methodological analysis of Gandhi with the teachings of Jesus, who concludes that there are no human beings that you can exclude from the grace of God.

During the time I was a troubleshooter for FOR, I was in and out of Birmingham, Alabama. In those years we called the city “Bombingham” because of the bombs that went off in black homes, churches. I would go in and see what was happening and give support and give the National Council of Churches a report, and also to Martin. That helped prepare the groundwork for the SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference] campaign, for which I was advance staff person. Bull Connor [the notorious segregationist police chief] sent a letter to the police about some “Negro” coming from Nashville to stir up trouble and we want to give him a good Birmingham welcome. That “Negro” was me.

I worked with the Little Rock Nine, the students who integrated Central High School [in Little Rock, Arkansas]. As the White Citizens Council and the governor worked to get them out of that school, the students had been told not to fight back. I gave them a quick two-, three-hour course in fighting back with nonviolence. Four or five of them gave me credit for saving their lives. I went back many times working with them and working with white students, too – about 100 of them, who were actively engaged in supporting them and confronting segregation. There were very courageous white kids who took beatings.

Lefer: Can you say more about the Nashville campaign?

Lawson: Maybe the first thing to point out is that it was never merely about desegregating lunch counters but was really about pulling down all those White and Colored signs. It was about department stores teaching their clerks to treat black people with dignity and good cheer and not in a reluctant hostile fashion. Just like the bus drivers in Birmingham, the drivers in Nashville insulted black riders all the time. It bored into the soul of the black community. You never knew when a white driver would mess over a respected person in the community. A woman could not try on a hat if she wanted to buy it, or a dress. A man could not try on a pair of shoes. Mothers could not have their children try on clothing or shoes. All this grotesque indignity! We in Nashville were the first group in the country that made as our demand the desegregation of a downtown in the South, confronting all the humiliation and indignity. No one else targeted that goal.

That goal and the training – using the picket line and sit-in and boycott – were all taught in workshops in preparation for the campaign. So from when school started in September till Christmas break, we met weekly for two or three hours. It was a community event. We had pastors and housewives and mothers as well as students. Ralph Abernathy, Martin King, and I were the unpaid staff of SCLC, working steadily – the only three – and we were all pastors of churches that primarily supported us.

Lefer: Was being pastor of Centenary Methodist your day job?

Lawson: It was my source of income. But more, we knew that we couldn’t be faithful pastors of our congregations without dealing with segregation and racism – those everyday experiences in the lives of our parishioners that had to be transformed. I have always known that what my people are doing in their work, how they earn their living, is a critical part of my ministry. It’s not secondary, any more than children are secondary to the congregation. Ministry is not primarily preaching and worshipping on a Sunday morning, as significant and important as I think that is. Ministry and service involve my connecting with people and trying to help them be strengthened in their fight, in their struggle. My dad and Martin’s dad felt the same way, and we learned from their example.

Lefer: After the Movement years didn’t you continue nonviolent organizing with the labor unions?

Lawson: Yes, I began working in Los Angeles with Local 11 [Restaurant and Hotel Workers Union], holding nonviolence workshops in the early 1990s. With Local 11, I wanted first of all to help people develop the character and the courage to organize. The workers were heavily intimidated and harassed on the work scene so that they were not willing to talk about their work pain, their wages. We found a major barrier in their fears, frustrations, and complicated acquiescence. Some of that produced anger in them, some of it also produced abuse in the family. But what we decided to do was to work on one-on-one activities – and I called it evangelism. We taught going to the worker in his community, in his home – and not doing this once, but doing it systematically, maybe once a week, for as long as it took. The organizer was to be generous and kindly throughout, use no harsh language, and approach the person with compassion and love. Do not concentrate on getting the person to join a union – concentrate on helping the worker talk about his situation on the job, in the family, in the community. Get to the point where the worker is talking about his fear, his frustrations, his pain. So the organizer concentrates on allowing the person to talk, to get his story out. Then find the right questions to ask to allow the worker to analyze the story that he’s told.

What I had found in my ministry – and I did not really fully understand it at the time and I don’t fully understand it now – but what that did was ignite a spark in the worker to begin to come to terms with his personal journey. And the worker formed a bond with the organizer, and the worker took small steps on the job to express himself, and the worker proceeded to help his family to understand what he was going through on that job and how much it hurt. So the worker began to build a small frame of another community who began to understand his plight, began to sympathize. Then, with the organizer, it meant beginning to connect with other workers and beginning to realize that organizing with them is the key to changing his scenery. That represents nonviolence: helping this harassed person re-find his basic humanity and talk about it. This approach came directly from my understanding of nonviolence and my experiences in the Civil Rights Movement.

I also began to hold conversations with other clergy, getting them involved in recognizing that poverty, and economic injustice, even among workers, is a major wrong that has to be corrected. In 1996, I invited a number of my colleagues to come to talk about this. We organized Clergy and Laity United for Economic Justice (CLUE) to get clergy involved in the plight of the poor worker. We would get a local congregation to organize an Economic Justice committee where they began by investigating their own congregation and their own people – that is, find out how many poor folk we have who are working people. Find out how many union members we have. Find out what their situations are. It also meant looking at church staff. Are we participating in poverty wages? We have to clean up our own act.

Then on the other side of the coin, we asked the janitors, one of the groups we worked with, “How many of you are members of churches, synagogues?” And always, hands went up. So my second question was, “Have you talked with your rabbis, with your pastors? Have you sat down with your priest and talked to him about your job situation, and your family situation?” That helped the union organizers recognize that a natural ally would be the congregations where they had members. And bridges began to be formed. What CLUE did was counsel the clergy about what it is they were finding and seeing. We inspired them to find the character and the spirituality to speak up. And we also engaged with the workers in civil disobedience actions and we were arrested, which brought media attention, visibility, to the cause and won over public opinion. We also enlisted the political apparatus, insisting that justice was one of the rallying cries, which produced this country and it has to be an essential part of what community means.

A Different Notion of Conversion

Lefer: You once told a story about using your fists on someone. So how did you come to your commitment to nonviolence?

Lawson: Oh yes! When I was four, my dad was appointed to the St. James African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Massillon, Ohio. And I probably romanticize it, but for me it became another kind of womb that nurtured and framed and formed me. At the same time, however, it is the first time that I became aware of people who called me racial slurs, on the street where we lived and in the parks. Even by that time I had a sense of my own worth, and my response was to slap the person or to fight. My mother was very much opposed to violence in all its different forms, and said so. My Dad was not, and in fact, when he was a pastor in Alabama and South Carolina, he carried a gun and he showed us that gun. I remember that very well.

But just why I struck out with my fists? That’s all I knew in the sense of insisting that you’re going to treat me as a human being. But you can be taught compassion in the family and in your church, and that will become a very powerful force in your life.

When I was in 4th or 5th grade, I came home from school, and my mother had an errand for me to run. It took me up Second Avenue to Main Street where I made a left turn and just after I turned left onto the Lincoln Way block, the main business section, there was a car parked at the curb. The windows were all open – it was a warm, beautiful day, and as I approached on the sidewalk, a child stood up in the front seat and yelled the “N” word at me. And I went over to the car and slapped the child. I ran on and finished the errand, and ran on back home.

Then, in the kitchen with my mother, I told her about this incident. And she said to me, “Jimmy, what good did that do? Jimmy, there must be a better way.”

That moment was a numinous experience, an experience in which the whole world stood still. And to this day I do not know what really happened at that moment in that house. We were a fairly noisy household. There were at least eleven of us and we had a piano and radios, so there was always noise and something going on. How that place was so still that day, I can never, never know. But in any case, it was. The world stood still. And in the midst of that experience, I heard a voice which I later began to recognize was my own voice, and yet it was not my voice because it didn’t come from me. It came from far away beyond me, and it was also in the depth of me. That voice said, “Jimmy, never again will you get angry on the playground and smack and fight. Never again.” And then I heard it say, “You will find a better way.” So I did from that moment on never again strike out at youngsters who used the “N” word on me. I never again got angry and engaged in a fight on the playground. I tried to find a better way.

Lefer: Did you find it?

Lawson: Some time later, on the street, almost the exact same sequence occurred. I was running an errand on Lincoln Way. A child in a parked car yelled a name at me. But this time I went over and I didn’t hit the child. I talked to the child. I asked his name and I gave him my name, in a way that was not confronting him but engaging with him. We had a good conversation. I took the time to let the child see and touch and know me. And I ended by telling him he should not call people names. We parted in a friendly way. I wanted to wait for the parents and talk to them too, but I did have that errand to run, and in the end I couldn’t keep waiting.

Lefer: Is it a struggle to give up the anger? Is it a decision you made at that moment in the kitchen, or is it something you work on constantly?

Lawson: Well, you know you still have to work on it, past 80. But no, it was, as I say, it was a numinous moment and it changed my life. That doesn’t mean that I didn’t get angry in the Movement. It’s just that you do what the great religions all teach: Be angry but do not sin. Be angry but don’t be foolish. Be angry, but direct it in a way that is commensurate with who you are as a human being.

I came to recognize that walking the extra mile, turning the other cheek,

praying for the enemy, and seeing the enemy as a fellow human being

was a resistance movement.

Between those years – 4th or 5th grade – and college, in 1947, I was a reader. Jesus fascinated me; so I read the four Gospels, and read and reread The Sermon on the Mount (Matthew: 5-7), where “turn the other cheek” is mentioned. And as I looked for a better way, that’s what I practiced all through junior high and high school. By the end of my high school years, I came to recognize that walking the extra mile, turning the other cheek, praying for the enemy, and seeing the enemy as a fellow human being was a resistance movement. It was not acquiescence or a passivity. I saw it as a place where my own life grew in strength inwardly, and where I had actually seen people changed because I responded with the other cheek. I went the second mile with them.

Then in 1949 I read the black theologian Howard Thurman, who said that the Gospel of Jesus is the survival kit for people whose backs are up against the wall. His book, Jesus and the Disinherited (New York: Abingdon-Cokesbury Press, 1949) reaffirmed my own experience. Thurman says that the oppressed will be angry, they will have great fears of all kinds, they will practice deceit, and he calls these “the hounds of hell” for these people. He talks about the way in which the anger can consume you and destroy you, so the management of that anger is important. And he says the Gospel of Jesus is a vehicle for handling and dissolving that anger and directing it.

We think of the Eastern religions as teaching us to detach and handle our emotions well. In my experience, Jesus of Nazareth has been a major force for my detaching myself from my fears and not being overcome by fear. Gandhi said that he read The Sermon on the Mount every day as a part of his reflections and meditations.

Lefer: I’m listening to you talk about Jesus at a time when we see so much fundamentalist hard-line religion. You are a deeply religious Christian and I’m trying to figure out how you do it – how you work very comfortably with people of all faiths, and people like me of no religious faith. Is that a spiritual understanding, or is it pragmatic, for political purposes?

Lawson: It’s spiritual. I maintain that anyone who gets arrested by the spiritual urges of life, by God, or by a sense of eternity, or by the gift of life itself and the universe in which we live, they get transformed. They get changed, personally, so that love and compassion become fundamental to their understanding.

Lefer: Do you have a different notion of what “conversion” entails?

Lawson: In conversion, what changes is the sense of belonging to life, belonging to God, belonging to the universe – and that what the person has come to see and feel and know embraces all humankind. I think many fundamentalists don’t have that deep sense of conversion and transformation into the agency of love and compassion.

Lefer: So that is why you sometimes substitute the word “life-force” for “God”? And the way you define faith for those without faith?

Lawson: I do not define faith as very different from the way in which Jesus defined it. Jesus uses that word to mean faith in God, because most folk believed in God and didn’t think that they got on earth by themselves. So Jesus meant that the person had faith in God, which encompasses life, that he knew his life was meant to be, that he belonged to God, and that his life was meant to explore the possibilities of access and opportunity, that you cannot be human and alive if you do not have faith. It’s faith that makes you wake up in the morning, makes you get up, causes you to have goals and purposes for the day, causes you to love, and to have confidence in the universe, have confidence in life.

This faith also makes me critical of religion, when they insist their faithful has to believe in dogma, or believe the earth is flat. That’s not really faith! Faith is the dynamic of getting connected to the gift of life, and you don’t have to do that by believing in God. I think the artist does this in ways that can teach us. I think many of the great scientists have done this in ways that teach us faith.

How can you claim to love the God who is invisible

if you hate the neighbor you can see?

The use of the Scriptures of the Bible has become very idolatrous in many different ways. Take the clergy who condemn same-sex marriage and pretend that it’s in the Bible. But the Bible does not know the word “homosexual.” It doesn’t know the word “heterosexual.” It does not have any kind of modern concept of human sexuality. That’s a 20th-century concept. How can you claim to love the God who is invisible if you hate the neighbor you can see?

A Highly Organized and Disciplined Affair

Lefer: You’ve said the movement doesn’t need a Gandhi or a Martin Luther King. But don’t we need leaders?

Lawson: Certainly we do. Always. You cannot have a human movement in which some people do not emerge as particularly able and competent in the struggle. When we think about why the Great Society wasn’t continued, what is forgotten is that the assassinations in the 1960s cleared the way for the emergence of Reagan. What would have happened if the Kennedys had lived and Malcolm X in his transformation and Martin Luther King and Medgar Evers and a range of other people? I’m thinking of any number of the Black Panthers who were killed, like Fred Hampton in Chicago. Those killings robbed the social awakening of the times of so many highly intelligent, creative human beings. When you kill off your best in that fashion, what are you doing about the future of your country? A movement will produce captains and generals. We lost many of them.

Lefer: You use military language a lot and I imagine some people criticize your use of the language of war.

Lawson: Bernard Lafayette called our Nashville workshops a course in nonviolence that was equivalent to having gone to West Point for military purposes. There are similarities between armies and the military and nonviolence. We call for our troops to be willing to suffer and die or be injured and hurt. So there has to be a doctrine of suffering. Over the years I’ve heard people say, “Well, if I do it nonviolently, I’m going to get hurt.” In nonviolence, we have to teach that you can be injured; you can be killed in this action, in this work.

Lefer: When you use the language of war, doesn’t it also emphasize that nonviolence is a powerful force?

Lawson: The military are the most highly organized people for violence, and when I use some military language, I am indicating the extent to which nonviolence must also be a highly organized and disciplined affair. It is an action that engages in serious study, investigation, analyzing, understanding the scene and the problem you’re trying to deal with and then organizing to do it. Activism has to have strategic plans. It has to have long-term and short-term goals. It must try to institutionalize the process.

Gandhi did not like “passive resistance,” “non-resistance” – which were Christian terms. He did not like “pacifism.” He was not satisfied with any of the historic terms used out of either Western Christianity or Western pacifism, and I didn’t like those terms either. I adopted Gandhi’s term of “nonviolence,” and that made more sense to me. Part of my critique of pacifism was that, in my college years, many of the people at the Fellowship of Reconciliation and the American Friends Service Committee said that love is non-coercive, that love could not pretend to power. And that did not strike home with me. It was clear to me that I had been empowered and that I had met power.

I’ll never forget the very first question that King asked me in the first workshop on nonviolence that I helped to lead for Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) in Columbia, South Carolina was about power. I knew that Martin was being besieged by all the pacifists in the country who were saying, “You’re too aggressive. You’re too militant.” So I answered him that nonviolence uses power. The Greeks defined power as the capacity to accomplish purpose. Power is a Creation-given thing. Nonviolence seeks to engender and transform power in every way possible. Our movements did not use power as the police did, did not use power as segregation did, but we pushed by engendering the demonstration, the economic boycott, we encouraged the reconfiguration of power so that power could be used to desegregate and to change.

Lefer: Is there a point where nonviolence won’t work anymore? Does society reach a point where things have gone too far?

Lawson: Before we decide that nonviolence won’t work, we should do a deep historical analysis of where the violence has not worked. Violence has not worked in the Middle East. It’s only escalated for 80 or 100 years. Until we de-escalate the military budget in the U.S. and turn that budget into plowshares, building a world class educational system that embraces every boy and girl anywhere in the country, until these things begin to happen on a serious note, we can’t know if there’s a place where nonviolence will not work.

I think most people in the United States want a more peaceful society and want peace in the world, but they do not recognize that in many ways their own attitudes prevent peace. White people in particular are afraid of wrestling with the issues of racism. Men are unwilling to give up their perceived superiority in dealing with the issue of sexism. Violence has persuaded many white male leaders in the United States that we have the right to have 8,000 nuclear weapons but Iran does not have the same right. Israel has the right to nuclear weapons but North Korea not. All of that is a double ethical standard. How do you have a world in which we have ethical principles that apply to women but not to men? That apply to white people but not to black people, or to black people but not to white people? I mean, how do you do this?

Over the millions of years of our journey, the wisdom of the human race developed ethical standards for us human beings on a personal individual basis, but these are the standards that states repudiate. Thou shalt not kill! I know of no ethical system that wants to reverse that and say, Thou shalt kill.

We can only have a world that will really provide for babies’ health and security if we the people not only demand of ourselves high standards, but demand that our corporate entities and government must do the same. And we must stop pretending that this is not possible.

Lefer: You’ve been teaching nonviolent theory and action for a very long time and we haven’t done a whole lot with what you’ve taught us. Have we let you down?

Lawson: I don’t see the changes that I would hope for, but I also recognize that may be me rather than the folk I’ve taught. It may be because I have not been persistent enough in institutionalizing the process. So I don’t put all the criticism out there. I look at myself, too. And then let’s recognize that there is still yet time to change this.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Diane Lefer is an author, playwright, and activist whose books include the historical novel, The Fiery Alphabet (Tucson, Arizona: Loose Leaves Publishing, 2013) about the tensions among science, religious dogma, and mysticism in the 18th century; and The Blessing Next to the Wound: A Story of Art, Activism, and Transformation (Herndon, Virginia: Lantern Books, 2010), which she co-authored with Hector Aristizabal. Her short stories have won much acclaim, and she is the recipient of the Mary McCarthy Short Fiction Award. James Morris Lawson, Jr. (b.1928) is professor emeritus at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. He was a leading theoretician and tactician of nonviolence in the Civil Rights Movement. During the 1960s, he served as a mentor to the Nashville Student Movement and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and to this day continues to train activists in nonviolence. The interview is courtesy archives.forusa.org, but also see FOR’s revised site, forusa.org.