Island of Peace: Lanza del Vasto and the Community of the Ark

by Mark Shepard

We are accused of going against the times. We are doing that deliberately and with all our strength.

— Lanza del Vasto

The machine enslaves, the hand sets free.

— Lanza del Vasto

Tucked away in the windswept mountains of Languedoc in southern France is a small island of peace known as the Community of the Ark. Founded and formed by Lanza del Vasto—often called Mahatma Gandhi’s “first disciple in the West”—the Ark is a model of a nonviolent social order, an alternative to the overt and hidden violence of our times.

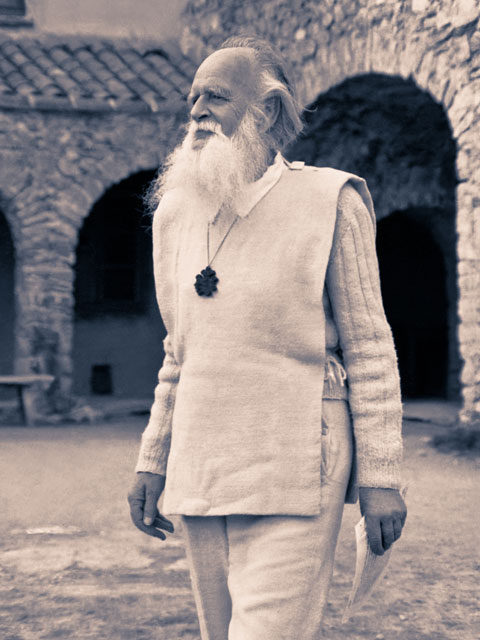

Joseph Jean Lanza del Vasto (1901-1981) was an Italian aristocrat deeply concerned about this violence. In 1936, Lanza traveled to India to meet Gandhi, the one person he thought might know how violence could be uprooted. Gandhi gave Lanza a new name: Shantidas, “Servant of Peace.” And Lanza returned to Europe with hopes of starting a “Gandhian Order in the West”.

In 1948 the news came of Gandhi’s assassination. Lanza felt the right time had come, and he founded the first Community of the Ark on a small rented farm in southwest France. This first community, though, was a fiasco. Many who came to live weren’t suited to community life or were not in accord with the community’s principles.

The community dissolved, but was soon reestablished on an estate in the Rhone Valley. This time, anyone wanting to become a full member—a “Companion”—had to go through a three-year apprenticeship and then be approved unanimously by the other Companions.

Even so, the community grew. In 1963, the community bought 1200 acres of farmland and forest in the mountains of southern France. Included on the land were several villages deserted since World War I, their half-ruined buildings made of stone, in the traditional architecture of the region. The Companions rebuilt and expanded one of these villages, La Borie Noble, to serve as their new home.

When I visited the community in 1979, the Companions had spread to three other “villages” on the land. Altogether, the community held over 100 residents, including Companions, applicants, long-term visitors, and children. The residents came from almost every country of Western Europe, and even farther. Though the Ark in its early days had drawn mostly intellectuals and aristocrats, residents now came from a wide range of backgrounds.

Besides this “mother community,” the Ark already had smaller branch communities in other parts of France, several other European countries, and Quebec. In all the communities combined, there were about 140.

What stood out most about the Ark was that it was a community of workers. The Companions believed strongly in the principle of “bread labor,” expounded by Gandhi and Tolstoy. This principle held that everyone who is able should share the physical work required to produce life’s basic needs, such as food and clothing.

According to the Companions, the practice of bread labor avoided the kind of oppression that develops when some people try to shirk their fair share of necessary labor. The practice also avoided division into classes of workers and non-workers. And it helped restrain material desires, which often grow unreasonable when someone else works to satisfy them. For these reasons, the Companions saw bread labor as the key to a “nonviolent economy”—an economy that abuses neither people nor nature.

While practicing bread labor, the Companions also aimed at producing everything they used—though, when I visited in 1979, they were still far from that goal. In this way, they were trying to break their links with the modern economy, which they saw as built on injustices toward the poor, the Third World, and the earth. They preferred to use simple tools, powered by hand or animal, believing that complicated machinery is a product of human greed. Simple tools, they said, benefit the worker, building physical, mental, and spiritual health.

The Companions grow all their vegetables and much of their grain using horses and hand methods in organic agriculture. A dairy at La Borie Noble provides milk and cheese. (No animals are raised for meat, because the Companions reject killing animals for food.)

The Companions place high importance on crafts. The women spin wool and weave it into cloth for garments, providing some of the community’s clothing, plus some garments for sale outside. Other crafts practiced at the Ark include carpentry, fine woodworking, stonecutting, blacksmithing, pottery, and printing. In all these crafts, only hand tools are used.

The spirit of the Ark is embodied in its crafts. Objects are made with an eye to beauty and elegance, never only to function. Each is carefully and lovingly decorated. Still, it is not the object that is most important. The main purpose of any work, they say, is to enrich the worker.

The Companions are trying to be self-sufficient in energy as in other ways. Firewood cut from the community’s forests is used for indoor heating, water heating, and some cooking. They use almost no electricity. Candles are used for indoor lighting, and vegetables are stored in cellars without refrigeration. Still, they have run an electric line to run a flourmill in their bakery; and also use batteries for flashlights and small record players. They have restored a water-powered sawmill to generate electricity for producing lumber from the community’s forests.

Each person at the Ark works according to ability and receives according to need. No money is used within the community, and no Companion individually owns money—though money is available for such needs as medical treatment and transportation. The Companions also do not own individual property, except for personal items such as clothes and books. There is no economic basis at the Ark for placing one person above another.

Second in importance only to work is the spiritual life of the community. The Companions believe that peace among people can be achieved only when individuals gain inner peace. Each person is encouraged in the practice of his or her own religion, and there is a community spiritual discipline as well.

Most of the Companions are strong Catholics, but the Ark, and its spiritual discipline, has no ties to any single religion. Instead, the adherents of any religion are welcome in the community. The Companions see this as an important part of setting a nonviolent example, since religious intolerance so often creates conflict in society at large.

Work, worship, and other aspects of community life are woven together in a daily routine that balances these activities and provides a sense of rhythm. The routine helps the Companions find the inner peace they seek. At La Borie Noble, an old church bell sounds to mark off each portion of the day.

It is still dark when the bell first announces the day’s beginning. At 6:00 A. M., many gather for yoga exercises and meditation in the community’s Common Room—a long, low room of white-washed plaster walls and a varnished pine floor.

An hour later, most of the community gathers for morning prayers, held in the Common Room, or outside if the harsh weather of those mountains permits. The Companions recite prayers taken from the Christian tradition that would also be acceptable to adherents of any faith. At the end, each person greets each other with the “kiss of peace.”

A simple breakfast follows, with families eating separately in their apartments and single people together in the kitchen. Work begins at 8:00 and continues until noon. Each hour, the tolling of the bell interrupts all work, calling the community to worship—either to a few minutes of prayer in small groups, or to a moment of silent inward reflection.

At 12:30, the community gathers for lunch in the Common Room, or outside, when it is warm. People sit on wide reed mats laid around the edge of the room, and the food is placed on a table in the center. On the day I attended, a woman led the singing of the Ark’s grace.

Lord, bless this meal

From which we draw the strength to serve you.

Give bread to those who haven’t any,

And hunger and thirst for righteousness

To those who have more than enough.

People got up to fill their bowls at the center table. The food was cooked simply, without spices, but had a rich flavor of its own. Lunch was the main social event of the day, so there was much talk and laughter.

Work started again at 2:00 and lasted until 6:00, with hourly pauses for worship as in the morning. At dinner, once again families ate apart and single people together, though the food had been prepared communally. Supper was also the time for special dinner gatherings in private apartments.

At 8:00, Companions gather in the chapel to recite the vows of their Order—Bread Labor, Self-Purification, Nonviolence, and so on. They then join the rest of the community for prayers in the Common Room or around a bonfire in the courtyard of the main building. The day ends as it began, with the kiss of peace.

This daily rhythm continues through the seasons in the celebration of festivals, seen as chances for the community to celebrate its unity and, by celebrating it, to strengthen it. The festivals are held about once a month—whenever Companions can find a reasonable excuse for one—so Companions are usually preparing for one festival or another. On festival days, the Companions dress in white woolen garments handmade at the Ark. Each festival is different, but there is always feasting, dancing, and singing.

Singing at the Ark runs through the days and seasons like a golden thread. Nearly every gathering of the community is an occasion for unaccompanied singing, which had reached a state of fine art under Lanza del Vasto’s late wife Chanterelle. Most of the songs are by Lanza and Chanterelle, usually on religious themes, and have the feeling of church music from the Middle Ages, but modern at the same time. The Companions’ recordings have won international awards.

Just as the Ark has tried to build a nonviolent economy, it has tried to build a nonviolent government as well—a government free of compulsion. To this end, the Companions conduct all their business by consensus. Coordinators are chosen for each area of work and for each “village” to help manage day-to-day affairs.

Lanza himself occupied the highest office in the Order of the Ark, the office of “Patriarch.” Though the power of this office had always been circumscribed, he had wielded that power a great deal in the stormy early years of the Ark. Then, as the community became more stable and united, the Patriarch’s authority shifted to the Companions as a whole.

Today the office is mostly honorary and advisory, and the title “Patriarch” is no longer used. Pierre Parodi, Shantidas’s successor from 1981 to 1989, was instead called “the Pilgrim”.

To maintain discipline in the community without coercion, Companions use the system of “responsibility and co-responsibility.” Responsibility means that each person should take on a suitable penance for a wrong he or she commits, whether or not known to others.

If the offender fails to own up, the principle of “co-responsibility” comes into play. Another person, seeing the wrong, has to approach the offender in private and point out the fault. But if the offender refuses to acknowledge it and the accuser remains convinced, the accuser has to assume the penance. The accuser might fast, or take on work the other failed to do, or anything else suitable. Generally, this leads the offender to recognize the fault and assume the penance.

The Companions have placed themselves well off the beaten path, but they keep close contact with the outside world in order to spread their message. A thousand or more visitors come each year and stay for varying lengths of time. During the summer, the Ark seems more like a training center than a community. Lanza del Vasto, Parodi, and other Companions have traveled extensively to spread the message of the Ark, and the Companions have also reached out into the larger society with a series of nonviolent action campaigns, models of strict Gandhian nonviolence. These included the first-ever occupation of a nuclear power facility, in 1958! The Companions also aided farmers on the nearby Larzac plateau in a successful campaign to block expansion of an army base. This campaign had helped provide a model for later European mass actions that in turn inspired the launching of the American anti-nuclear movement at Seabrook, New Hampshire.

Though the people of the Ark are trying to affect the larger society, they do not expect to bring about widespread change. They see Western civilization as racing to its self-destruction, propelled by greed, ignorance, violence, and a technology that magnifies all of these. They doubt the momentum can be checked, but they hope they can at least serve as a model to those who rebuild from the ashes—and perhaps themselves survive as seeds of a new society.

References:

Del VASTO, Lanza. Make Straight the Way of the Lord: An Anthology of the Philosophical Writings of Lanza del Vasto, New York: Knopf, 1974.

Del VASTO, Lanza. Warriors of Peace: Writings on the Technique of Nonviolence, New York: Knopf, 1974.

Del VASTO, Lanza. Return to the Source, New York: Schocken, 1972. Includes an account of Shantidas’s stay with Gandhi.

SHEPARD, Mark. The Community of the Ark: A Visit with Lanza del Vasto, His Fellow Disciples of Mahatma Gandhi, and Their Utopian Community in France (20th Anniversary Edition). Friday Harbor, Washington: Simple Productions, 2011. A personal, detailed account of my visit.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Mark Shepard describes himself as having been among other things “a journalist specializing in Mahatma Gandhi, the Gandhi movement, nonviolence, peacemaking, simple living, and utopian societies; a musician on flute, drums, and other instruments; and a would-be professional poet”. He is the author of Gandhi Today; Mahatma Gandhi and his Myths, and The Community of the Ark, besides which he is also the author of children’s books. His website can be consulted for excerpts from his books and further biographical information. For more information about L’Arche, the English language version of their site is at this link. But L’Arche’s French site has more information than the English about the original community and can be found here.