Gandhi in Olive Country: Palestinians Revel in the Nonviolent Struggle

by Aimee Ginsburg

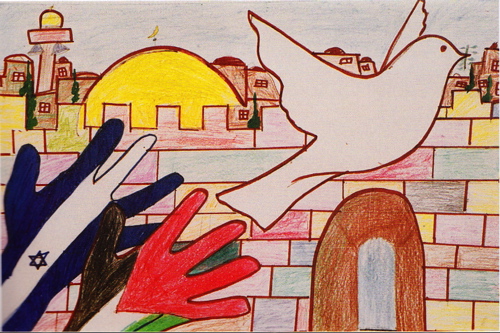

Palestinian children’s art courtesy patheos.com

Editor’s Preface: We have posted a series of articles on the Palestinian nonviolent movement, and especially about the struggle in the village of Bil’in. These can be accessed via our Islamic Nonviolence category in the right sidebar. Please also see the editor’s note at the end for information about the author, links, and acknowledgments. JG

I’m sitting with Robert Hirschfield at the corner ice cream shop, tall windows facing the street, steaming mint tea in our glass mugs. Outside, a large group of angry young Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) supporters are waving their fists and their kaffiyas (headdresses), shouting slogans against the Hamas massacre of fourteen PLO members in Gaza.

We are in Ramallah [March 2008], the interim capital of Palestine, two American Jewish writers, and I am thinking we are crazy. Hirschfield, 68, is comfortable. He has been traveling through Palestine for a month now, researching his book on Palestinian nonviolence. He likes it here. “There is an aliveness, an open and present friendliness, a warmth,” he says. Outside, the shouting gets louder. Sorry to say, I think of the Israeli journalist, Daniel Pearl, who was murdered in Pakistan; while Hirschfield thinks of Mahatma Gandhi.

It was the visit of Arun Gandhi, the Mahatma’s grandson, to Palestine in 2004 that first caught Hirschfield’s interest. “In the United States,” Hirschfield says, “Palestinians are seldom portrayed as anything other than terrorists. Sure the terror is real, and Israel must defend herself. But why stigmatize the whole of the Palestinian people?” It was this point Arun Gandhi addressed on his Palestine visit. “Imagine yourselves marching by the thousands behind your leaders, demanding the right to be treated as human beings,” he told a large audience of Palestinians and their Israeli sympathizers. “Sit at the roadblocks and sing your songs. March to the wall and dance your dances.”

No mass march followed this perhaps naïve plea, but Arun’s message was absorbed, part of a continuing Palestinian debate on the viability of a nonviolent resolution to the Israeli occupation. “We are looking forward to a Palestinian satyagraha,” answered Hanna Amireh, of the PLO executive committee, to Arun. “In spite of the fact that Palestine might not be ready for him, Mahatma Gandhi would find an abiding place in the Palestinian struggle for freedom.”

The most publicized nonviolent “revolt” is happening at the village of Bil’in. When Israel confiscated, in 2004, several thousands of acres of this village to build the security wall between the two countries from north to south, hundreds of Palestinians and Israelis started coming to weekly Friday nonviolent resistance actions here. It included chaining themselves to olive trees and holding weddings on the confiscated land. Some 800 have been injured, many have been arrested, The Israeli Supreme Court recently ruled in their favor, but only partially. The protests continue. Abdullah Abu Rahma, the director of the coalition at Bil’in, told Hirschfield, “What Gandhi did for his people, I want to do for mine.”

“The history of Palestinian nonviolence is long and courageous, but not well-known,” says Hirschfield, a writer’s writer whose discovery of the Palestinian nonviolence movement has developed into an intensely personal passion, leading him all the way from New York’s Lower East Side to the towns and alleyways of Palestine. “It is not quite a story of ahimsa, not in the spiritual sense. Usually, nonviolence activism has been used here as a way to an end. But certainly, there are many who choose nonviolence because it is just that — nonviolent.”

We are joined at the Ramallah ice cream shop by Hizami Jabri, a 36 year-old father of five young girls, who has served two terms in Israeli jails and was shot in his shoulder during a violent agitation. “I started to ask myself, how could I have a good life? How could my people have a good life? This violence, it cannot bring a good life,” says Jabri, a member of the Palestine Authority’s preventive security force by day, a nonviolence trainer after hours for the NGO, Middle East Nonviolence and Democracy (MEND). He tells us, as many do, that the success of nonviolence in India gives him strength, inspiration. There is shy pride in his hazel eyes when he says, “My daughters have taught nonviolent conflict resolution to all the other kids in the neighborhood. They are a new generation.”

Hirschfield tells us of another NGO called Combatants for Peace, which unites Israeli and Palestinian ex-fighters in nonviolent actions against the Israeli occupation. One Palestinian leader of this group, Bassam Aramin, an ex-Fatah fighter who served years in Israeli jails, lost his ten-year-old daughter to a stray Israeli bullet last spring but has not changed his mind about his path; Aramin’s Israeli counterpart, Arik, lost his sister in a Palestinian suicide attack. Hirschfield has written about these men in one of his powerful essays: “They are fighters wanting to reframe the fight, wanting a future for their children emptied of the wall posters of martyrs.”

My crash course on the history of the Palestinian nonviolence movement is set in stunning scenery, seen through the windows of the small local buses. Beige and olive hillsides meet the cream blue sky in a clearly marked line; an aging man with a child on his back walks slowly through a fallow field. Hirschfield, his white hair worn in an Einstein-like halo, tells me that most Palestinian nonviolent resistance (dating back as far as 1936) has emerged from the grassroots, not taught by a leader or a specific ideology. But nonviolent tactics received a boost during the 1988 uprising, the First Intifada, when the underground leadership called the people to use organized, classic tactics such as boycotts of Israeli goods, tax strikes, planting vegetable gardens, even knitting and sewing their own clothes. The people responded, and a peace process resulted, but not any real liberation. Now, after another very violent Intifada, inter-Palestinian violence is at an all-time high.

“Nonviolence is not a garment to be put on and off at will. Its seat is in the heart,

and it must be an inseparable part of our being.”

We have reached Bethlehem, the birthplace of Jesus Christ, through a massive and intimidating checkpoint. We are visiting the Holy Land Trust (HLT), one of the several Palestinian NGOs dedicated to strengthening and promoting nonviolence on the West Bank. In the hallway, a billboard carries a photo of Mahatma Gandhi with the quote: “Nonviolence is not a garment to be put on and off at will. Its seat is in the heart, and it must be an inseparable part of our being.” On the hallway bookshelf, a well-worn set of Gandhi’s writings, brought back by Mubarak Awad (called Abu Gandhi) from his India pilgrimage (yatra) some 25 years ago. “I do not believe Gandhi would agree to terms such as ‘Gandhian’,” says Sami Awad, Mubarak’s nephew and the executive director of the HLT. “This term holds a sense of division, separateness. But the HLT is founded on the philosophy and the work of Gandhi, in the political, social and spiritual sense.” The windows look out over a valley where a large, clustered Israeli settlement blocks the view of the olive groves on the ancient white rock slopes.

Olive trees in Palestine have special significance because of their longevity. When one plants and tends a new olive tree, it is an act of unselfish love towards future generations. The Palestinian territories are covered in olive groves, but thousands of trees have also been cut down to build the Wall. Replanting new olive trees has become a major form of civil disobedience, along with rebuilding demolished houses, demonstrating at the Wall, and boycotting Israeli goods. As Arun Gandhi said, “I am often reminded of the famous quote by Gandhi, ‘First they ignore you, then they ridicule you . . .’ The great thing about this quote is the fact that Gandhi did not go on to say, then they fight you, then they lose. Gandhi said, ‘then YOU WIN.’ In nonviolence, there are no losers, only winners.”

These days, there are never enough seats in the nonviolence training sessions given by HLT and many other Palestinian groups to supply the rapidly growing demand from women, villagers, PLO fighters, even once a clandestine unit of Hamas, for such training. Over the course of three days, fifty or more participants learn to recognize and express their anger, learn nonviolent conflict resolution, and strategies for civil disobedience. “It’s amazing,” says Eilda Zaghmout Bandak, the 26-year-old charismatic executive officer of HLT. Participants immediately begin to apply these techniques in their daily lives. We have always felt so helpless, at the mercy of others. Now we feel empowered.”

This good news remains under-reported, even in Israel, where there is strong support for an independent Palestinian country. Three years ago, wealthy American businesspeople sponsored The Gandhi Campaign, and the Hollywood film, Gandhi, dubbed in Arabic, was shown in towns and villages across Palestine and Gaza, with the hope that it would inspire nonviolence. Ben Kingsley, the movie’s star, was guest of honor at the premiere. The next day, Avishai Margalit, a writer for Israel’s left-leaning newspaper Haaretz, asked Palestinian friends if there ever could be a Palestinian Gandhi, or whether Mubarak Awad had “failed”. And his friends told him, “Nonviolent struggle is perceived in Palestine as unmanly. There is a strong belief that what was taken by force must be regained by force.” But then the left-wing Israeli scholar and blogger Ran HaCohen wrote in response: “The Palestinians don’t have to watch a Gandhi film. There are thousands of Palestinian Gandhis out there; whole villages that demonstrate daily and peacefully against the robbery of their land and livelihood. Still, the only voice we hear is the voice of commentators and movie stars wondering, ‘Where is the Palestinian Gandhi?’”

Hirschfield would agree. He is writing his book about these remarkable people, and about his mother as well, a deeply orthodox Jew who lost twenty-five members of her family in the Holocaust. “My mother was appalled by the violence in the world. She taught me that I must use my life to heal this world. Israel’s actions in Palestine fill me with anger, and with immense sadness.” He is one of many, on both sides of the grey wall, dedicated to tearing it down by themselves being, as Gandhi famously said, the change they want to see.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Aimee Ginsburg is an American/Israeli writer who lived in India for a decade. She has been the India correspondent for Yedioth Ahronoth, Israel’s largest daily, and writes on Indian culture and spirituality for many publications. She is also the founding director of the Theodore Bikel Legacy Project, and was married to Bikel from 2013 until his death in 2015. This article has been shared with outlookindia.com, and mkgandhi.org, under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.