They Refused To Let Justice Be Crucified

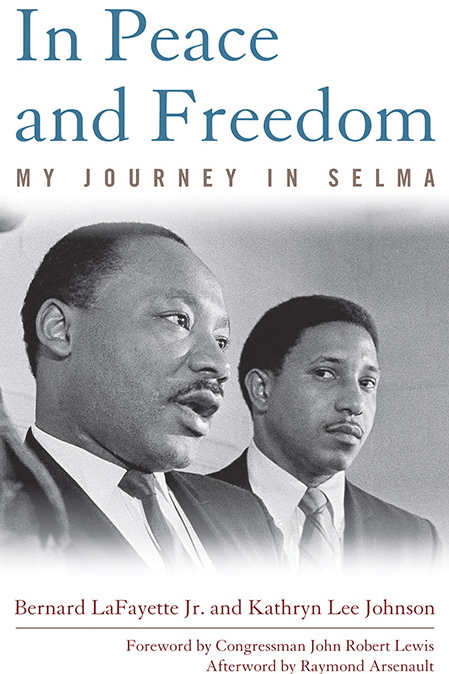

Dust wrapper courtesy Univ. Press of Kentucky

During their hard-fought struggle to overcome nearly impossible odds and win voting rights for African American citizens who had been disenfranchised for 100 years, civil rights activists marched down the long and treacherous road that led from the brutal battlefield of Selma, Alabama, through a seemingly endless gauntlet of beatings, bombings, bloodshed, gunshots, martyrdom, and a tri-state assassination conspiracy.

Even though their nonviolent efforts to win the right to vote were met with some of the most shocking violence of the civil rights era, the Freedom Movement stood its ground and claimed perhaps its most significant and far-reaching victory for human rights — the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

As a young man, Bernard LaFayette was chosen to become the key organizer of this dangerous and bloody struggle, and he offers a fascinating insider’s look into the Selma campaign in interviews and in his recent book, In Peace and Freedom, My Journey in Selma. The lessons in community organizing, in this highly insightful case study, are deeply valuable and relevant to today’s human rights activists.

Find the Cost of Freedom

In opening up this chapter of the Freedom Movement to reveal its lessons, it is important to approach it, not as some academic case study in nonviolence, but with the clear-eyed realization of the terrible price that was paid in bloodshed and the loss of life. LaFayette has given us something far more profound than just another case study of nonviolence. He has also opened our eyes to the heartbreaking sacrifices made by decent and compassionate people such as Jimmie Lee Jackson, Viola Liuzzo and Rev. James Reeb, who selflessly gave their very lives in their commitment to fighting for the most basic of human rights.