What Cesar Chavez Did Right — and Wrong

by José Antonio Orosco

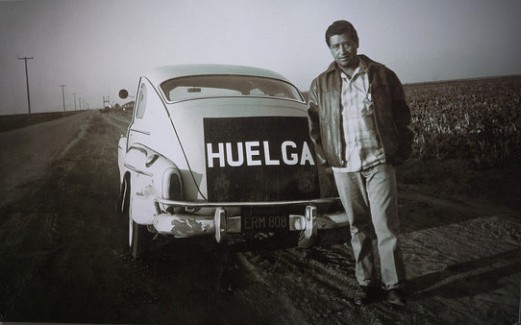

Cesar Chavez on strike; courtesy Flickr/Jay Galvin

The recent release of Diego Luna’s new film, Cesar Chavez: An American Hero (starring Michael Peña and John Malcovitch), and the documentary Cesar’s Last Fast directed by Richard Ray Perez (premiered at the Sundance Film Festival), give us new opportunities to reflect on the lessons of Chavez’s life and activism. While his charismatic leadership turned him into a powerful force for justice, an unyielding grip on his position of authority ultimately weakened the organization he worked to build.

The title An American Hero is appropriate. Chavez’s life unfolded like a classic American success story. His family lost everything during the Great Depression, and Chavez managed to get only an eighth grade education in between stints working in the fields of California. Yet he went on to found a powerful organization that forever changed American history by giving voice to some of the most disadvantaged members of our society. There are valuable lessons to take from his determination, as well as his stubbornness.

Start from the margins

Before establishing the United Farm Workers, Chavez was a community organizer in an established civil rights group called the Community Services Organization. CSO was built around Saul Alinsky’s principles of organizing and funded partly through Alinsky’s Industrial Areas Foundation in Chicago. Chavez eventually rose to be CSO’s executive director because of his ability to mobilize communities to stand up for themselves against police brutality and municipal neglect. Although he was not making a fortune from CSO, he drew a steady salary that his wife, Helen, and their children could appreciate.

Then, after a decade, he gave it all up. He had proposed that CSO begin to advocate for the farm workers of California, and the board of directors rejected the idea, so Chavez resigned his leadership position and lost the only source of income for his family. For several years, he and Helen, along with fellow organizer Dolores Huerta, traveled throughout California’s Central Valley sustained by their dream of a union for farm workers, made up by farm workers.

Chavez’s decision to leave CSO teaches us the power of working outside the state and established organizations to make social change. Working for peace and social justice sometimes requires developing alternative institutions that prefigure the kind of inclusive world in which we want to live. Chavez could have stayed at CSO, doing good work to assist Mexican-American voters throughout California. But he knew that already existing groups don’t always serve people living at the margins. Later, after the UFW established itself, Chavez continued to insist that farm workers develop their own credit unions, co-ops and alternative service agencies.

Sacrifice to minimize the suffering of others

Chavez’s willingness to sacrifice and give up the safety and security of a steady life is surely one of the most inspiring aspects of his character. He would display this kind of commitment many times in his career, most notably during his three major hunger fasts. Chavez’s last fast in 1988, which is the subject of Richard Ray Perez’s new documentary, went on for 36 days. He described his suffering as slight in comparison to the pain felt by the farm workers poisoned by indiscriminate pesticide use. He explained that he wanted to use his own suffering to draw attention to this injustice.

“The evil is far greater than even I had thought it to be, it threatens to choke out the life of our people and also the life system that supports us all,” Chavez said. “The solution to this deadly crisis will not be found in the arrogance of the powerful, but in solidarity with the weak and helpless.”

While Chavez demonstrates that sacrifice is a necessary component of social justice work, it is equally important to note his ongoing self-reflection on the uses of that sacrifice. He never called the fasts “hunger strikes” because they were not meant to be coercive. Instead, they were meant to raise awareness about the extent of structural injustice in society.

In ways like this, Chavez was constantly examining how his personal choices might impact the suffering of the most vulnerable members of society, and how he might use his position to bring to light their struggles. He wanted us all to question our most ordinary decisions, from what we eat to where we shop. He explained that his fasting was intended to encourage everyone to think about what we take for granted in our everyday lives. “It pains me that we continue to shop without protest at stores that offer grapes; that we eat in restaurants that display them; that we are too patient and understanding with those who serve them to us,” he said. “The fast, then, was for those who know they could or should do more — for those who, by not acting, become bystanders in the poisoning of our food and the people who produce it.”

Use multiple measures of success

By the late 1980s, the UFW was in trouble. It had lost several significant union certification elections and was hemorrhaging members. The pesticide fast had failed to spur growers to reduce their use of chemicals on grapes. In comparison to the 1960s and 70s — when the UFW catalyzed historic legislative changes and attracted the support of high-profile politicians like Robert Kennedy — the last years of Chavez’s life looked like a failure.

Chavez was undaunted, but not because of unwarranted optimism. He heeded Martin Luther King’s teaching from the Birmingham jail: Social change in the United States will not come automatically because of the goodness of its people. It will come from communities becoming organized and raising enough creative tension that the unjust status quo cannot continue.

Too often, activists measure their success only in terms of recognition from the state or from the size of rallies or demonstrations. Chavez recommended thinking about movement success in terms of whether our organizing is creating new connections and bringing people together — especially those that are usually marginalized in society — in ways that develop their capacities and confidence, and that help them to articulate new, transformative visions: “Our opponents must understand that it’s not just a union we have built,” he said. “Unions, like other institutions, can come and go. But we’re more than an institution!”

Charisma can cripple a movement

Chavez’s career also contains a cautionary tale for social justice activists. Most accounts of his leadership tend to wrap up after the successes of the grape boycott and the legislative victories that won protections for farm workers in California. Recent books by Miriam Pawel (The Crusades of Cesar Chavez: A Biography, New York & London: Bloomsbury, 2014) and Frank Bardacke (Trampling Out the Vintage: Cesar Chavez and the Two Souls of the United Farm Workers, New York: Verso Books, 2011), however, reveal disturbing patterns of heavy-handedness by Chavez that verged on paranoia in his later years. Chavez did not seem able to handle challenges to his personal authority.

When some farm workers in the Salinas Valley proposed an alternative, less-centralized form of decision making for the UFW in 1981, he had them purged from the union, along with any members of the central leadership that had allied themselves with those whom Chavez called “traitors.” When organizers admitted fatigue, he was not above publicly shaming them for their inability to sacrifice, creating a culture of guilt and fear of his wrath. Some see the decline of the UFW in recent decades as a result of it being too tied to the personality of Chavez. His own undoing was the result of building an echo chamber of followers around himself, a mirror that reflected his saintly image but that was not always connected to the needs and interests of the grassroots.

This lesson is not meant to detract from Chavez’s legacy, or to lend fuel to those who would prefer to dismiss him altogether. Instead, it should be encouragement to those who strive for horizontal leadership that mutually supports and empowers a democratic network of organizers across many movements. Building a movement culture that spreads leadership and authority among a wide number of activists can be a potent way to strengthen efforts grounded in labor, the environment and identity that are at the center of so much social justice work today.

We ought to be grateful that Hollywood is bringing attention to La Causa and depicting community organizing among Latinos as a place of heroic struggle. Cesar Chavez has become an icon for social justice and a symbol of Latino success and power. But while we celebrate his legacy, we should also take heed of the way that he very humanly failed to live up to his own ideals, and learn how we can build movements that help us all to be the best individuals, and the best organizers, that we can be.

EDITOR’S NOTE: José-Antonio Orosco is the author of Cesar Chavez and the Common Sense of Nonviolence (Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press, 2008) He teaches at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Ore., where he is director of the Peace Studies program and co-founder of the Anarres Project for Alternative Futures; courtesy of Creative Commons sharing with wagingnonviolence.org, per April 7, 2014. For a critical assessment of Chavez’s career a recent New Yorker article is one of the better.