The Gandhi-Reynolds Correspondence in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection: Letters to and about Reginald Reynolds from Mahatma Gandhi, 1929-1946

by Barbara E. Addison

Editor’s Preface: We previously posted Reynolds’ article, “The Practical Application of Nonviolence,” as part of our War Resisters’ International project, found at this link. Both that article and this are additions to our ongoing series on Gandhi’s influence on pacifist and nonviolent movements in Europe and the U.S. Please consult the note at the end of the article for further information about the author. JG

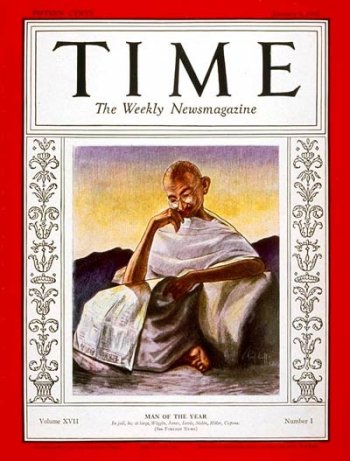

“Gandhi: Man of the Year”; Time, Jan. 5, 1931; courtesy www.kamat.com

Reginald Reynolds, a young British Quaker, corresponded with Mohandas K. Gandhi during one of the most crucial periods in Gandhi’s life and in modern Indian history: the Salt March (Salt Satyagraha) and the beginning of the 1930 Indian civil disobedience campaign against the British Raj. Reynolds was a resident in Gandhi’s ashram (spiritual retreat) at Sabarmati from 1929 to 1930. In March 1930, Gandhi appointed him to deliver a lengthy statement (generally known as “Gandhi’s Ultimatum”) to the British viceroy explaining the reasons for Gandhi’s revolt against British authority. The Gandhi-Reynolds correspondence, written primarily between 1929 and 1932, reveals Gandhi as an indefatigable political strategist, spiritual leader, and warm, attentive friend.

In 1931, Reynolds sold three of his Gandhi letters to Charles F. Jenkins, a prominent Philadelphia businessman and manuscript collector. He was parting with the correspondence in order to raise funds for his British-based organization, “The Friends of India.” He told Jenkins: “I find myself able to help them by surrendering some of my most valued possessions,” adding that he had many other letters, but had selected these as the ones with which he felt he could best part. “The rest are far too personal and precious to part with at all, and a fortune would not purchase them!” (1) The letters apparently were left to the Swarthmore College Peace Collection in Jenkins’s will, and were added to the collection in 1952. Reynolds himself donated sixteen of his “personal and precious” letters to the Peace Collection some time between 1952 and his death in 1958. Barbara Addison’s article, including scans of all the original documents, may be accessed at this link, “Gandhi Letters in the Swarthmore College Peace Collection.” (2)

The Gandhi-Reynolds Correspondence

Reginald Reynolds was twenty-four years old when he arrived at Mahatma Gandhi’s ashram in 1929. Previously, after two years’ study at Woodbrooke College in Birmingham, England, he had tried various occupations (actor, schoolmaster, sheepskin trimmer in his family’s firm) with little success.

Reynolds had met Horace Alexander while at Woodbrooke. Alexander, like Reynolds, was a British Quaker pacifist, who served as an advisor to Mohandas Gandhi. Realizing that he was at loose ends, Alexander suggested that Reynolds go to Gandhi’s ashram in India, assuring him that Gandhi would find a use for him. Alexander wrote about Reynolds to the Mahatma in Fall 1929, and Gandhi replied (October 12, 1929) that Reynolds would be welcome at the ashram, and that Alexander could “rest assured that no stone will be left unturned to conserve [Reynolds'] health so far as it is humanly possible.” Alexander must have mentioned to Gandhi that Reynolds had suffered from ill health for much of his life.

Gandhi was away on a speaking tour when Reynolds first arrived at the ashram at Sabarmati. Gandhi had written to him on October 28, 1929, welcoming him to the ashram, giving him extensive advice about health and spiritual matters, and asking him to correspond frequently and to freely give his impressions. One more encouraging letter followed (November 4, 1929). In an undated letter (December 2, 1929) came Gandhi’s first recorded impression of Reynolds: “My dear Reynolds, I saw your nose bleeding. You need not feel distressed about it. Take rest for awhile and sip cold water through the nose & bring it out through the throat & splash cold water over the head & at the back of it.” Like many of Gandhi’s letters, it was written on a “Silence Day.” On occasion Gandhi would maintain a day during which he would not speak to anyone. Reynolds noted that there was absolutely no privacy in Gandhi’s life, and a day of silence offered his only chance to meditate, and to deal with writing and correspondence. (3)

At their first meeting, Reynolds was struck by Gandhi’s bird-like demeanor, his toothless smile and the general lack of distinction in his appearance. Reynolds regarded Gandhi as aged, although he was only 60 years old at the time of their meeting. He was impressed, nonetheless, by Gandhi’s vitality, his vision, honesty, tactical and strategic abilities and his personal charm. Gandhi’s sense of humor was to be one of Reynolds’ most welcome discoveries. Gandhi was highly logical and analytical, yet capable of real personal affection. He encouraged his followers to address him, and regard him, as “Bapu” — Dad, or Daddy.

Reynolds had studied Indian economic and social history in England, and he wanted to make amends for the suffering of the Indians at the hands of the British during their long colonization. Reynolds had written to Gandhi that he had been refused entry into a Hindu temple. “I had seen so much and heard and read so much of the humiliation of Indians in their own country (and often in England, too) that it had given me positive pleasure, as I well remember, to find the tables turned on the Englishman, even though the Englishman happened to be myself. (4) But “Bapu” could not look at it that way. He replied on November 11, 1929, “the hideous truth is that this bar is a variety of the curse of untouchability . . .”

Another side of Gandhi, his “scorching passion for truth” Reynolds found at times unsettling. “I mentioned in his hearing that I was going to try to get out of [an understanding to attend an engagement], given in an unwary moment — I was very tired and had nothing to say at the meeting. I shall not forget his look of genuine incredulity as he said, ‘But you can’t go back on your word!’ Completely out-quakered by a Hindu, I had to give in and go.” (5)

Reynolds admired Gandhi’s moral force, but he disagreed with him on the subject of sex and other sociological questions. In a letter of April 14, 1938, Gandhi was to chastise Reynolds for having married a divorced woman, implying that Reynolds was unable to keep his sexual passion in check. As Gandhi wrote: “I must however ask one question. Did you think it lawful to sexually love the married lady or do you say that although it was wrong you could not help yourselves, and having fallen, the only honourable course for you was to marry? I need to know this, if I may, to see how far we have drifted from each other and what philosophy guides us. The fact that you are a seeker of Truth is enough to sustain the bond between us.” Reynolds viewed Gandhi as he would a great Catholic saint, admiring wholeheartedly his character and spiritual power. (6)

Reynolds appreciated that Gandhi was skilled in what would later be called public and media relations. Gandhi broadcast his message as widely as possible with radio and newsreels, as well as with traditional methods. He enlisted British supporters such as Reynolds to help him sway public opinion in Britain, against the force of British propaganda for the Empire.

In spite of the tremendous burdens he carried, Gandhi remained a gracious host, welcoming to strangers, concerned for their comfort. He wrote to Reynolds on a Silence Day (December 3, 1929), “I am somewhat troubled about the guests [Sherwood Eddy and Kirby Page] who are coming today. I am most anxious that they should have the necessary creature comforts supplied to them so long as it is within our power to do so. Will you please act as co-host with Sitla Sahai & see that they do not feel strangers in a strange place?” Reynolds recalled in A Quest for Gandhi:

Only those who know the pressure of work under which such notes were written will ever appreciate their full value. There was at that time a first-class political crisis, with political leaders continually arriving at the ashram for consultations. Gandhi was, of course, giving this matter his closest attention. He was also editing Young India and writing most of the articles in it, dealing with his vast correspondence, personally superintending the work of the All-India Spinners’ Association and concerned with the administration of the ashram. At one time, I remember, he was also acting as the spokesman of the Ahmedabad mill-workers in a dispute with the employers. He was frequently asked to arbitrate personally in many personal and political disputes, and I know not what else besides. Add to this the fact that he never missed his morning walk (when few could keep pace with him) or his daily hour at the spinning wheel or the morning and evening prayers it was certainly an achievement that he was never too busy to be the perfect host, and that he had time for the troubles of every child at the ashram. (7)

Gandhi apologized to Reynolds for a long silence in an undated letter probably written between February 2nd and February 14th 1930: “my correspondence is lying neglected; I simply cannot cope with it.” He then made a political reference: “The real thing is likely to begin not before March.” The “real thing” was the civil disobedience campaign planned for spring of 1930, in anticipation of the failure of negotiations with the British government to grant India greater independence. On February 4, 1930, he urged Reynolds again to write freely to him, reminding Reynolds that he considered the journal Young India his weekly letter to friends.

In his autobiography, My Life and Crimes, Reynolds described daily life in the ashram: “working in the fields, learning to spin and weave, trying to master the elements of Hindi, studying Indian politics and social history, living a semi-monastic life of austere simplicity and acquiring a crude grounding in Gandhi’s philosophy of life, which touched everything from the technique of non-violent resistance to the most minute details of diet and conduct.” (8)

Reynolds quickly became devoted to Gandhi and his work: against caste-divisions, for Muslim-Hindu unity, an improved role of women in society, and efforts to encourage rural self-employment. The ashram included members of the “untouchable” caste whom Gandhi especially championed, calling them Harijans (children of God). Gandhi, in turn, seemed pleased with his young British acolyte, and delegated to Reynolds tasks to further Gandhi’s ambitions for Indian self-rule. Gandhi was struck by Reynolds’ pro-Indian (and anti-British) attitudes. In a letter of introduction for Reynolds to C. Y. Chintamani, Gandhi wrote: “This is to introduce a young English friend, Mr. Reynolds, who has come to India in a spirit of purest service. He has no axe of his own to grind and he holds views that may startle even the most advanced nationalist.” (Gandhi to C. Y. Chintamani, February 4, 1930) He urged Reynolds to “identify yourself with the activities of the Ashram. I am anxious for it to become an abode of peace purity & strength. You I hold to be a gift from God for the advancement of that work.” (March 13, 1930)

Reynolds soon discover that, together with Gandhi’s charm and attentiveness, he had an iron will regarding his principles. A particularly vicious article against Gandhi had appeared in the Indian Daily Mail. Reynolds wrote an explosive rejoinder in the Bombay Chronicle, for which Gandhi castigated him. (March 31, 1930) “I have been daily thinking of you and thinking of writing to you . . . I did not like your writing in the Chronicle. It is not ahimsa. The Indian Daily Mail did not deserve the notice you took of it. If the notice had to be taken, the way was bad. Why should you spoil a good case by bad adjectives? And when you have a good cause never descend to personalities. Yours is a case where the saying ‘Resist not evil’ applies. It means ‘Resist not evil with evil.’ You have neutralised the evil writing of the I.D.M. by a writing of the same kind. That you had a good case makes no difference . . . The [Indian Daily Mail] writing was a piece of violence. You have supported your good case with counter-violence. So you see, what I want to emphasise is not merely bad manners. It is the underlying violence that worries me. Is this not quite clear to you? If it is, I would like you to promise to yourself and never to write any such thing without submitting it to someone in whose non-violence you have faith.”

Fences were mended by April 4, 1930, when Gandhi wrote : “I was delighted to have your letter. There is no question of restoration of confidence, for it was never lost. Assimilation of true ahimsa is a slow and sometimes painful process. And very few realize that there is such a thing as mental himsa and that it needs to be eradicated. (9) It is to me a great joy that you saw the thing at once. I do not mind the other letters you have written. I should be glad if you will make another promise to yourself, viz., never to write for the Press for the time being. Let Young India be your sole vehicle for the time being. What do you say to your writing a brief note in Young India repenting of the unconscious indiscretion?” Gandhi wrote again on April 6: “The letter from Wilson [F.W. Wilson, editor of the Indian Daily Mail] is quite good. God will keep you out of harm’s way.” Reynolds was grateful and relieved for Gandhi’s gracious forgiveness, but “I only knew that Gandhiji’s ‘gift from God’ had proved rather a flop and that he was now asking me to do something that would cost a hell of a lot in personal pride. So I did as he asked”, that is, by apologizing to Wilson. (10) But Reynolds never did write the repentant note in Young India.

This personal exchange is all the more remarkable in that Gandhi was embroiled in conflict with the British colonial government, and had that day (April 6, 1930) committed an historic act of civil disobedience as the culmination of the Salt Satyagraha, by picking up salt from India’s shore.

Gandhi had been the iconic leader of the Indian National Congress Party since the end of the First World War, although not usually involved in its day-to-day affairs. The Congress Party fought for India’s freedom from colonial rule; it had members from a wide variety of Indian religious, ethnic, and economic classes. Reynolds was among Gandhi’s followers at an historic meeting of the Congress Party in Lahore from December 1929 to January 1930. On January 1st, 1930, a resolution for independence was voted upon, and a flag representing Indian independence was raised. Gandhi then retired to the Sabarmati ashram to plan a campaign of civil disobedience to call attention to the iniquities of British rule. Violence was in the air. Indian nationalist terrorists had exploded a bomb under the train of Lord Irwin, the British viceroy, as he was returning to Delhi in December 1929. (Irwin was unhurt.) Gandhi and his followers were refining their plans for the nonviolent civil disobedience campaign, which would become known as the “Salt Satyagraha.” Salt was taxed by the British in India so that the burden fell most heavily on the poor. Worse, Indians were legally forbidden to collect the free salt, which lay upon their own shores. By leading the Salt Satyagraha, Gandhi had chosen a simple but extremely effective (and photogenic) method to attract and mobilize followers, at home and internationally.

Before launching the civil disobedience campaign, Gandhi wrote a letter to Lord Irwin, explaining his motives and justifying his actions. Gandhi asked Reynolds to be his messenger to the British government by delivering the letter to Irwin, thus giving Reynolds the opportunity to contribute to one of the crucial moments in modern Indian history. Later known as “Gandhi’s Ultimatum,” the letter was courteous, addressing Irwin as “Dear Friend”:

Satyagraha Ashram, Sabarmati, March 2, 1930.

Dear Friend:

Before embarking on Civil Disobedience and taking the risk I have dreaded to take all these years, I would fain approach you and find a way out. My personal faith is absolutely clear. I cannot intentionally hurt anything that lives, much less fellow human beings, even though they may do the greatest wrong to me and mine. Whilst, therefore, I hold the British rule to be a curse, I do not intend harm to a single Englishman or to any legitimate interest he may have in India.

I must not be misunderstood. Though I hold the British rule in India to be a curse, I do not therefore consider Englishmen in general to be worse than any other people on earth. I have the privilege of claiming many Englishmen among my dearest friends. Indeed, much that I have learnt of the evil of British rule is due to the writings of frank and courageous Englishmen who have not hesitated to tell the unpalatable truth about that rule. . . (11)

…This letter is not in any way intended as a threat, but is a simple and sacred duty peremptory on a civil resister. Therefore I am having it specially delivered by a young English friend, who believes in the Indian cause and is a full believer in non-violence and whom Providence seems to have sent to me as it were for the very purpose.

I remain

Your sincere friend

M. K. Gandhi

The young English friend sent by Providence was Reginald Reynolds.

The Viceroy did not reply to the letter. Instead, his secretary wrote: “His Excellency…. regrets to learn that you contemplate a course of action which is clearly bound to involve violation of the law and danger to the public peace.” Gandhi replied in Young India: “On bended knee, I asked for bread and received a stone instead.” The London Times reprinted the text on March 13, 1930:

Mr. Gandhi, in to-day’s issue of Young India, criticises the Viceroy’s reply to his letter. “On bended knee,” he writes, “I asked for bread, but received a stone instead. The Viceroy represents a nation that does not easily give in and does not easily repent. Entreaty never convinces it. It listens to physical force…and can go mad over a football match in which may be broken bones, and goes into ecstasies over blood-curdling accounts of war. It will not listen to mere resistless suffering. It will not part with the millions it annually drains from India in reply to any argument however convincing. The Viceregal reply does not surprise me. But I know the salt tax has to go, and many other things with it. My letter means what it says. The reply says I contemplate a course of action, which is clearly bound to involve a violation of the law and a danger to public peace. In spite of a forest of books containing rules and regulations, the only law the nation knows is the will of the British administrators, and the only public peace the nation knows is the peace of the public prison. India is one vast, prison house. I repudiate this law, and regard it as my sacred duty to break the mournful monotony of compulsory peace that is choking the nation’s heart for want of a free vent.” (12)

Upon the rejection of his letter, Gandhi accelerated his preparations for the Salt March. He chose the followers who would accompany him, but Reynolds was not among them. Gandhi did not have enough confidence in Reynolds’ understanding of the concept of “satyagraha.” A satyagrahi looked upon all people as brothers and sisters, believing that the practice of love and self-suffering would bring about a change of heart in any opponent, and having faith that the power of love was great enough to melt the stoniest heart. The satyagrahi did not resist violence with violence. Reynolds had not yet achieved that state of being. “Left behind with the women and children, and a very few men who remained at Sabarmati, I was restless and have no doubt that my own letters to ‘Bapu’ reflected the fact.” (13)

News of Gandhi’s plans spread throughout the world, and telegrams of support began to pour into the tiny Ahmedabad post office. A prayer meeting was held on March 11th, attended by 10,000 supporters when Gandhi bid them goodbye. Fearing retaliatory violence by the British, everyone was aware that it could possibly be his final farewell. The marchers began at the ashram on March 12, 1930, and continued south for 241 miles (388 km) to the sea to the small village of Dandi, arriving on April 5th. Seventy-eight people accompanied Gandhi on the march to the sea with a larger number accompanying him part way. (14) When he reached the seashore, Gandhi was the first to commit civil disobedience by picking up salt, thereby breaking the law. The march received worldwide attention via newspaper, radio, and newsreel. (15)

The Salt March was only one part of the campaign to free India. The All-India Congress approved Gandhi’s campaign, and hoped that the country would respond. It organized committees in the provinces to continue to break the Salt Laws. As the civil disobedience movement spread across the country, British tactics soon turned brutal against the nonviolent protesters. Men, women, and children were killed and injured in demonstrations. Congress Party leaders and many thousands of people were arrested. On April 24, 1930, Gandhi wrote to Reynolds: “Just one line. My dear Reynolds, How will you fare about [Young India] now that Mahadev is off? I hope you are well both in mind and body. Love, Bapu.” Mahadev Haribhai Desai, a close associate of Gandhi’s, had been imprisoned for his civil disobedience.

Shortly after midnight on May 5th, Gandhi was arrested by British authorities and detained without trial, sentence, or known term of imprisonment, in anticipation of his plan to raid the Dharasana Salt Works. From prison, he wrote again to Reynolds on May 22nd: “My dear Reynolds, I have your love-letter as also news about you from Mira. By all means go. If you feel like coming & seeing me before you leave do come. There will be no difficulty about your seeing me. God be with you wherever you may be. Love, Bapu.” Writing in the margins of the letter, Gandhi continued: “I wanted to write to your fiancée, [Richenda Payne] but it was not to be. But if you send me her address, I would still write. Tell her I received her letter the day of my arrest. Bapu.” Reynolds tried to visit Gandhi in prison, but was curtly dismissed by prison officials. Two months later the Mahatma’s brother, Narandas Gandhi, wrote to Reynolds, saying “Bapu does not take interviews since you went to Yeravda [prison].” Gandhi had refused to accept any visitors unless Reynolds would also be allowed to see him. (16)

Due to ill health, Reynolds went back to England in the summer of 1930, and would not return to India until 1949. He continued his extensive study of Indian social and economic history, which would culminate in his best-known book, The White Sahibs in India, first published in London in 1937. Reynolds maintained contact with Gandhi and the ashram, and continued to work for Indian independence through involvement with the India Conciliation Group, Friends of India, the Indian Freedom Campaign, and as General Secretary of the No More War Movement.

In India, the success of the civil disobedience campaigns made the British government inclined to negotiate with the leaders of the Congress Party. British officials arranged a Round Table Conference, which opened in London on November 12, 1930, but Gandhi and members of the Indian National Congress, many of them imprisoned for civil disobedience, considered it a sham. Gandhi and more than 20 other Congress leaders were released from prison on January 26, 1931. Gandhi asked for an interview with Lord Irwin to discuss Congress Party participation in the second Round Table Conference, and cessation of the civil disobedience movement. They negotiated with cordiality in a series of meetings. The result was the Gandhi-Irwin Pact (also called the Delhi Pact) of March 1931 by which the civil disobedience campaign was called off, prisoners were released, and salt manufacture by the people was allowed. The Indian National Congress agreed to send representatives to a second Round Table Conference in London. There was no mention of independence, or even dominion status for India, conditions which Gandhi and Congress had long sought. Reynolds was disturbed and bewildered at what he viewed as Gandhi’s capitulation to the British in agreeing to attend the conference and calling off the civil disobedience campaign. In Quest for Gandhi Reynolds recalled:

As soon as negotiations were re-opened with the Government, I wrote [to Gandhi]. It was not, as it might appear, impertinent interference. I had a perfectly legitimate motive, which was that — as one of the few exponents of the Congress case in Britain — I ought to know just where they stood. It was of vital importance to me that I should understand the reasons for this change of front if I was to continue writing and speaking in defence of India and her leaders. Gandhiji’s reply to this letter was written from Delhi on February 23rd, 1931. It was much longer than most of his letters to me, and typed. (Most of the letters I had from him were in his own hand or — very rarely — dictated to an amanuensis.) The old man said he honoured me for my ‘long, frank and emphatic letter’, but after this and some other kind remarks he went on to say that he completely disagreed with me, giving his reasons. I was not in any way entitled to such an explanation, but it was typical of Gandhiji that he found time to offer it. Others who wrote to him with queries or criticisms at different times in his life invariably had the same experience. Bapu asked me to ‘remember…that Satyagraha is a method of carrying conviction and of converting by an appeal to reason and to the sympathetic chord in human beings. It relies upon the ultimate good in every human being.’ This I could appreciate– but I still could not see that it explained the change of policy. However, the letter invited further criticism if I was not convinced. ‘If this does not satisfy you,’ he wrote, ‘do by all means strive with me. You are entitled to do so…’ There followed words of appreciation and encouragement, referring to my efforts to present the Indian case in Britain. (17)

Another letter followed in April, 1931, the first letter in which Gandhi reminded Reynolds that he had dealt with Reynolds’ letter in Young India “as you had wished” and asking Reynolds not to desert the cause or give up on him. “I was still little more than a boy, and my support could have made only an infinitesimal difference to him. Yet he wrote, because, I think each human soul mattered so much to him. (18) In a personal aside, Gandhi asked for news of Reynolds’ broken engagement, telling him that he could always return to Sabarmati because “the Ashram is your second home.” For the first time Gandhi addressed the letter, not to “my dear Reynolds” as previously, but to “my dear Angada,” a reference to the Indian epic Ramayana, in which Angada, a monkey, was the messenger sent by Rama to negotiate the return of his wife. Gandhi was referring to Reynolds having been his emissary when he carried his letter to Irwin regarding the Salt March. In Quest for Gandhi, Reynolds described the epic Angada as “a white ape employed by the Gods when opening hostilities against the powers of Darkness.” (19)

Gandhi was clearly concerned about Reynolds, writing to C.F. Andrews (20) on May 5, 1931: “He is disconsolate towards the Settlement. The engagement with the girl whom he was to marry is broken. His pecuniary condition is bad. My whole heart goes out to him. I do not think that my reply to his letter in Young India has given him any satisfaction. I would like him to know that all is well and that the Settlement is not a surrender of principle. I would like you to go to him, argue out the matter with him and otherwise help him and draw him out of his seclusion. He is as good as gold and is very brave. Perhaps all that I have written to you is superfluous and that you have met him and had already known more about him than I have told you. But I could not restrain myself and you can sympathize with me having done such things much more often than I do.” Gandhi touched briefly on political matters: “Gujarat still absorbs my attention to the exclusion of everything else. Implementing the Settlement in the teeth of official sullenness, unwillingness and even opposition is a very difficult business…we are no nearer the Hindu-Muslim solution…”

Gandhi left for London on August 29, 1931, to attend the Second Round Table Conference, residing there as a guest of Muriel Lester (21) at Kingsley Hall in a poor section of the city. Reynolds was delighted to be the first person the Mahatma chose to see when he arrived in England. Gandhi used his time in Britain to spread his message as widely as possible to the international community. During his travels throughout England, he reiterated that he sought complete independence for India without bloodshed. He especially reached out to the Lancashire mill workers who were displaced because of his campaign against the use of British cloth in India. In an undated letter from October or November 1931, as he attended the conference, Gandhi replied to a letter from Reynolds: “Just a line in reply to your question whilst I am sitting at the Conference. I favour preference to Lancashire to help a partner nation in its distress, assuming of course that partnership was possible. Why should Japan complain that I prefer a partner in distress? If India becomes partner instead of remaining subject, there is no Empire. You must relate all my acts to Ahimsa. In Ahimsa there is no room for immoral expedience.” In Quest for Gandhi Reynolds recalled: “It was a reply to another critical query relating to policy justifying economic concessions which I had wrongly attributed to lack of firmness on his part. His letter made it clear that he did not offer these concessions from weakness, but out of sympathy for the British people, of whose economic problems he had learnt a good deal. He had been especially interested in the conditions of the Lancashire textile workers.” (22)

Gandhi considered the Second Round Table Conference a failure. India was no closer to freedom from the British, and Hindu-Muslim relations had worsened. He left England on December 5, 1931. Reynolds met him for the last time when he saw him off. Gandhi traveled throughout Europe, then sailed for India, arriving on December 28, 1931, to a very different political climate. Lord Willingdon had replaced Lord Irwin as viceroy. Willingdon was determined to clamp down on India’s recent hard-won gains from the British. He withdrew the concessions made under the Gandhi-Irwin Pact, and imposed drastic sanctions against the Indian National Congress. Gandhi, who only a few months previous had been a guest of King George V at Buckingham Palace, was arrested for sedition in January 4, 1932, and taken to the Yeravda Central Prison, once again His Majesty’s guest, but of a very different sort. Thousands of people were imprisoned under this policy of repression and were killed or badly wounded during nonviolent protests.

On September 16, 1932, Gandhi began a hunger strike, a “fast unto death,” in protest of the British government’s decision to separate India’s electoral system by caste, a move he believed would permanently and unfairly divide India’s social classes and stigmatize and discriminate against the lower classes. His six-day fast ended after the British government reversed their decision. Gandhi wrote three letters to Reynolds from prison shortly after the fast ended. The first, September 30, 1932, was only a few lines of “superfluous love.” On October 13th, obviously in answer to a letter from Reynolds about the fast, he replied: “Your dear letter. It is like a soothing draught. I knew that you & others whom I have in mind would see the inwardness of the fast. God let me down gently as a mother her child. And the glorious manifestation all over the land was more than that to me.” Gandhi closed by inquiring again about Reynolds’ life and welfare. On December [8th?], 1932, still in prison, he wrote of mutual acquaintances who were also imprisoned.

In the 1930s, there would be only one more communication from Gandhi to Reynolds, a postcard dated March 29, 1935, referring to David Pyke, a mutual acquaintance, and asking for news of Reynolds. Reynolds recalled: “The answer, had I given it, was that I did not expect him to approve of my general line, and preferred not to discuss it”:

From 1932 until the war my approach became increasingly political, moving fairly steadily to the left until I could see the Trotskyists at some distance to my right, looking very conservative. The effect of this absorption in politics was that my correspondence with Gandhiji became even less frequent, for I was excluding from my life all the things he held to be of greater importance than politics. One has always to remember that Gandhi was a politician only in a secondary and a very limited sense. (He never stood as a candidate for any legislature, never exercised the authority of any government, and never wanted to do so.)…[I wrote] three years later [1938], telling him some things, which I knew would not please him. In his reply he said: “My heart goes out to you. What does it matter that on some things -we don’t see eye to eye?” At the end of that letter he wrote: “The fact that you are a seeker of truth is enough to sustain the bond between us.” We had never been further apart in thought and in our objectives, yet he could write these unforgettable words of comradeship and affection. (23)

It was Reynolds’ last communication with Gandhi until after World War II.

Their final correspondence came in 1946. Reynolds felt that during the war, censorship would have prevented any real exchanges of interest. More importantly, Reynolds was renewing his views on pacifism. “I was ready once more, in 1945, to learn from the greatest man of our time what he could teach me about the sources of spiritual vision, of human understanding, of tolerance and charity. In this new mood I therefore wrote to Gandhiji again, feeling that much of what I had now learned was the result of my association with him fifteen years previously though it had taken years of trial and error (especially the latter) to show me how right he had really been.” (24)

In a letter misdated January 1, 1945 (he meant 1946), Gandhi again replied graciously to Reynolds, saying “your letter just presents you as I have known you” and warmly inviting him to return to India. Reynolds astutely commented later that Gandhi “never saw people merely as they were, but as what they could become.” Gandhi did not forget him. In To Live in Mankind, Reynolds recalled: “An Indian friend, returning from London two years later, saw the old man in December 1947 and recorded in a letter that he had ‘especially asked’ for information about me. So I know that at the time of his death [in 1948] I was still remembered with affection.” (25) “I know now that I have Bapu’s blessing and that our friendship is secure in the mind that never despaired of me, the Great Soul who will always see the Divine in all of us, however blurred the image of God may become to common sight.” (26) Although Reynolds had always maintained a nominal membership with Quakers, his experience with Gandhi and his later study and writing of the work of the Quaker “saint” and antislavery advocate John Woolman confirmed and gave form to a renewed faith: “A Hindu was therefore the chief instrument of my re-conversion to Christianity. I am eternally in debt to the Great Soul of Mohandas Gandhi.” (27)

In his later years, Reynolds described himself as a Quaker pacifist, anarchist and a supporter of nationalist movements for self-determination in India, Africa, and the Palestinian Arabs. He was a versatile and engaging author and lecturer. He wrote about Gandhi and India of course — his best known work was The White Sahibs in India (1937). Around 1945, at the time of his return to pacifism, Reynolds turned to the works of “Quaker saint” John Woolman, seeing parallels between the life and work of Gandhi and Woolman in their concern for the oppressed. The Wisdom of John Woolman was published in 1948. For enjoyment he wrote mock-serious works on beards and sanitation, and satiric verse for the New Statesman. His light-hearted autobiography, My Life and Crimes, was published in 1956.

Reginald Reynolds was a man of many talents: “Teacher, factory worker, salesman, General Secretary of the No More War Movement, letting agent, Civil Defence driver, partner in a socialist book centre, broadcaster, journalist, toy theatre dramatist…he loved to sing, dance, drink rough cider, watch horror films, lay bricks, cleave wood and, in fancy dress, to caper with a pantomime horse…his appeal was magnetic.” (28) Reynolds had married left-wing novelist Ethel Mannin in 1938. He returned to India in 1949 as a delegate to the World Pacifist Conference, and traveled throughout the world as Field Secretary to the British Friends Peace Committee. It was on one such visit to Australia that Reynolds died suddenly on December 16th, 1958, in Adelaide at age 53, of a cerebral hemorrhage. (29)

His obituary in the Quaker journal The Friend (London) described him as eccentric, a visionary and a prophet: “To him life was a continual plea for honesty, tolerance, racial equality, justice, truth and spiritual freedom for man. His protesting spirit and inquiring, amazingly versatile, mind took him at one moment to the American South into the heart of the Negro problem and the next moment to Japan to support a protest against hydrogen bombs…he would have gone anywhere to find truth.” (30)

Sources Consulted:

“Civil Disobedience Movement, 1930-1931, British India”,

http://www.indianetzone.com/35/civil_disobedience_movement_1930-1931_british_india.htm; accessed 18 January 2015.

Gandhi: 1915-1948: A Detailed Chronology. Compiled by C.B. Dalal. New Delhi: Gandhi Peace Foundation, 1971.

Gandhi, M.K. Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of India, 1958-1984.

Huxter, Robert. Reg and Ethel: Reginald Reynolds (1905-1958), His Life and Work and His Marriage to Ethel Mannin (1900-1984). York, England: Sessions Book Trust, 1992.

Muzumdar, Haridas. Gandhi Versus the Empire. New York, Universal Publishing Co., [c. 1932].

Reynolds, Reginald. Gandhi’s Fast: Its Cause and Significance. London: No More War Movement, [1932?].

Reynolds, Reginald. India, Gandhi and World Peace. London: Friends of India, [1931].

Reynolds, Reginald. “Letters from Bapu,” in Incidents of Gandhiji’s Life, edited by Chandrashanker Shukla. Bombay: Vora, 1949.

Reynolds, Reginald. Quest for Gandhi. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1952. First published in Great Britain under title: To Live in Mankind: a Quest for Gandhi.

“Round Table Conference”, http://www.indianetzone.com/24/the_round_table_conference.htm; accessed 18 January 2015.

Endnotes:

(1) Reginald Reynolds to Charles F. Jenkins, January 5, 1931. Swarthmore College Peace Collection CDG-B. Great Britain, Reynolds, Reginald.

(2) Also included are transcriptions of three letters referred to in the narrative which are not held by the Peace Collection: 1) Item 4 (November 11, 1929), 2) Item 7 (1930 undated [between February 2 and February 13, 1930]), and 3) Item 24 (April 14, 1938).

(3) Quest for Gandhi, p. 15.

(4) Letters from Bapu, p. 1.

(5) Quest for Gandhi, p. 47.

(6) Ibid, p. 48.

(7) Ibid, p. 15-16.

(8) Reynolds, Reginald, My Life and Crimes, p. 58.

(9) Underlining in the original.

(10) Quest for Gandhi, p. 56?

(11) About 2100 words follow. The entire letter may be seen at:

http://wikilivres.ca/wiki/First_Letter_to_Lord_Irwin

(12) Online at: http://archive.timesonline.co.uk/tol/viewArticle.arc?articleId=ARCHIVE-The_Times-1930-05-07-16-003&pageId=ARCHIVE-The_Times-1930-05-07-16

(13) Letters from Bapu, p. 3.

(14) Reg and Ethel, p. 57.

(15) Videos of the Salt March are available at youtube.com. Although Reynolds did not accompany Gandhi on the Salt March, a brief glimpse of him may be seen on the newsreel, identified as “Mr. Reginald Reynolds, the Englishman closely associated with the Nationalist leader.”

(16) Letters from Bapu, p. 4.

(17) Quest for Gandhi, p. 86-87.

(18) Letters from Bapu, p. 5.

(19) Quest for Gandhi, p. 93.

(20) C.F. Andrews (Charles Freer Andrews, 1871-1940) was a British Anglican clergyman and an early and stalwart ally of Gandhi and Indian freedom.

(21) Muriel Lester (1883-1968) was a founder of Kingsley Hall, a social settlement modeled after Toynbee Hall. An admirer of her work at Kingsley Hall invited her along on a thirteen-week visit to India in 1926-1927, where she became friends with Gandhi.

(22) To Live in Mankind, p. 89

(23) To Live in Mankind, p. 92-93.

(24) To Live in Mankind, p. 94.

(25) To Live in Mankind, p. 94.

(26) Letters from Bapu, p. 7.

(27) Letters from Bapu, p. 8-9.

(28) Reg and Ethel, p. 7-8.

(29) Reg and Ethel, p. 231.

(30) The Friend, Dec. 26, 1958, p. 1664.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Barbara E. Addison is Librarian of the Swarthmore College Peace Collection, and the Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College; article courtesy Barbara E. Addison and Swarthmore Peace Archive.